Many legends attribute the origins of Kung Fu to the Shàolín monastery 少林寺. However, long before the construction of this temple, a long martial tradition already existed in China, which has been, in some way, obscured by the fame of the monks.

When did the martial arts originate? Surely answering this question escapes our possibilities but, if we want to reach some degree of knowledge about it, we must first ask ourselves what is a martial art.

Let's begin first of all by the most obvious: the martial refers to the military, combat and war. From the moment our first primate ancestors stood on two legs, they had their hands free so that they could use tools and weapons to hunt or defend themselves.

The first weapons that humans used were undoubtedly the ones that nature gave them, like stones and cudgels. Later, our ancestors created others in an intentional way. Possibly the first of these weapons created by the hand of man was the spear that, at its earliest stage, could be obtained by simply sharpening the tip of a stick. Subsequently, carved stones were used tied to a rope, to be able to throw them and recover them quickly, or to make them turn and project them with greater power. Those were known in China as Fēi shí suǒ 飛石索.

Possibly, the first weapon created by man was the spear, which could be obtained by sharpening the tip of a stick.

Therefore, we can say that the martial exists since humankind exists. But are these activities, whether hunting or defending oneself, sufficient to form a martial art?

In Shǎnxī 陝西 province, remains of bows and arrows have been found, with an age of thirty thousand years, and it seems that the Yǎngsháo culture 仰韶文化 (5000-2000 BC), along the Yellow River, produced crossbows. Of course, archery requires a specific training and a martial culture beyond the coarse abilities needed to wield a stick or an axe and defend against wild animals.

We came here to the second question, the most tricky: what defines an art? To what extent do the warrior skills of primitive peoples constitute a martial art?

Art, besides having an expressive purpose, is characterized by rules, which can be aesthetic or functional and define what is correct or not (although art often evolves by breaking the rules to establish new ones), as well as for the existence of a technique. Therefore, in our understanding, martial arts did not exist as such until a specific technique and training was introduced to develop and perfect this technique, intentionally, through a set of rules.

In this sense, one of the earliest forms of combat that could be considered a martial art is the jiǎo dǐ 角抵, which consisted of a ludic form in which the combatants hit each other with helmets with ox horns. This style of combat was practiced already around the year 2700 BC and is considered to be the predecessor of current shuāi jiāo 摔跤. According to the legends, the jiǎo dǐ was used on one occasion in 2697 BC by the troops of the Yellow Emperor, Huáng Dì 黃帝, to confront a rebel army.

Jiǎo dǐ 角抵, a ludic form of combat in which the combatants hit each other with helmets with ox horns, is considered to be the predecessor of current shuāi jiāo 摔跤.

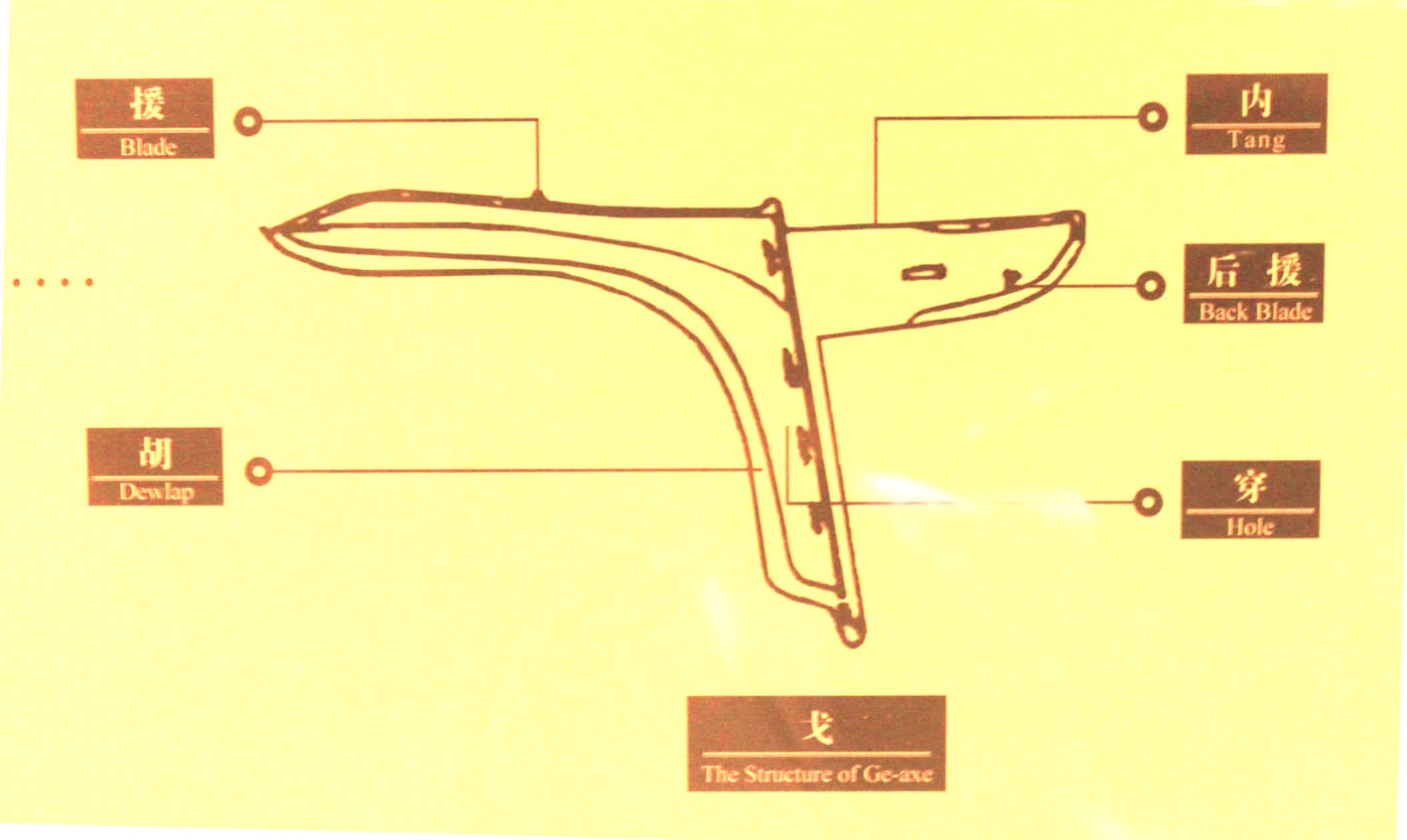

During the Bronze Age, corresponding to the Xià 夏dynasty (2070-1600 BC), new weapons were invented and manufactured, like the dagger-axe (gē 戈) or the broad sabre (dà dāo 大刀), among many others, and the first schools of archery were established.

Ancient dagger-axe (gē 戈) blades. Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nányuè 南越 King, Guangzhou 广州.

Structure of dagger-axe.

Later, in the Shāng 商dynasty (1766-1122 BC), the military strategy is notably developed, and the archery is established as the martial art par excellence of the time, requiring great skill and training to shoot targets in motion from a mobile position.

In the Zhōu 周 dynasty (1122-249 BC) the jiàn 劍 sword starts to be used in war. This is a double-edged sword which will become one of the most emblematic weapons of China (although these swords were already manufactured previously), and military dances (Wǔ Wǔ 武舞) appear, along with the training of forms, sequences or routines of techniques practiced in order to develop martial skills.

In the 6th century BC, the famous Sūn Zǐ Bīng Fǎ 孫子兵法 appears, The Art of War by Sūn Zǐ, a treatise of military strategy whose influence in the military arts has remained until today, when it is still studied even in the business field.

It is known that, during the Western Zhōu Dynasty 西周, there were already forms or routines of unarmed combat, although these were practiced only as preparation for weapon combat and not because they were considered to be useful themselves. It is at that same time that the concept of association between the martial and the intellectual, known as Wǔ Wén 武文, begins to develop. This concept considers that the ideal man should cultivate the two parts, as both complement each other. However, the martial arts are not exclusive patrimony of the elites, being practiced also among the rest of the population, and a type of combat known as Bó Zhí 搏執, "strike and seize", appears.

El shǒu bó 手搏 incluía ya los cuatro elementos básicos de las artes marciales chinas: dǎ 打o golpear con las manos, tī 踢o patear, ná 拿o controlar las articulaciones y shuāi 摔 o derribar.

In the Hàn 漢 dynasty (206 BC – 220 A.D.), the use of the jiàn sword as a weapon of war begins to decline, being replaced, on the one hand, by one-handed curved broadswords with a different weight distribution, heavier on the tip, which allowed a greater slicing power, and on the other hand, by two-handed straight sabres, of greater range. However, the jiàn sword will remain as the officers' sign of authority and as a ceremonial weapon. Simultaneously, the jiǎo dǐ becomes part of the regular military training, and were written various treatises of shǒu bó 手搏, a type of empty hand combat that included already the four basic elements present in current Chinese martial arts : dǎ 打 or hand strikes, tī 踢 or kicks, ná 拿 or joint control and shuāi 摔 or knock-downs.

Ancient jiàn 劍 swords. Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nányuè 南越 King, Guangzhou 广州.

During the Northern Wei 北魏 dynasty (386-535), martial arts are popularized among the upper classes of Chinese society as a form of exercise to maintain health, and unarmed combat becomes a ludic training. In the army, soldiers practise the spear on horseback and archery, both on horseback and on foot. The military spear has a length of 3 meters. In the Táng 唐朝 dynasty shorter spears appear, more useful in duels on foot against short weapons like curved sabers, and Lion Dance is born.

All this long tradition contrasts with the common belief Chinese martial arts originated in the Shàolín monastery, whose construction was not carried out until the year 495. We see that the Chinese already possessed a wide martial culture long before that time, which extended to different social strata and that encompassed combats and routines with and without weapons, and that were practiced both for military and recreational purposes and even to improve and maintain health. For all this, we can conclude that the martial had already been constituted as an art since many centuries before.

We have to keep in mind, then, that myths are widely spread in the field of Chinese martial arts. In another article we will examine the myth of Bodhidharma's role as founder of Shàolín Kung Fu, as well as the development of martial arts in this famous temple.