The Chinese military sabre is originally a cavalry weapon. With a heavy blade, it specializes in slashing, and has countless variants in terms of length and shape of both the blade and the handle, existing even two-handed sabres.

Dāo 刀 is a term that refers to a single-edged weapon, encompassing both sabres and long-pole weapons, such as the pǔ dāo 朴刀 or the zhǎnmǎdāo 斬馬刀.

However, while the term "sabre" refers to curved-blade weapons, the Chinese word dāo does not necessarily imply this characteristic.

The count below is not intended to be exhaustive, and does not in any way deplete all types of sabre that exist or have existed in China. The first classification we offer follows the chronological order of appearance, and is based on the shape of the blade, and there may be alternative classifications based on other criteria. Finally, we also mention some types of sabre that, although they could be found in the first classification, have some peculiar feature that makes them stand out.

The straight sabre or zhíbèidāo 直背刀

The first dāo appear during the Shāng 商 dynasty. At that time, Chinese metallurgy was already highly developed, showing a technique of working bronze far superior to that of other contemporary kingdoms. These early dāo are characterized by their straight blade, so they are known as zhídāo 直刀 or zhíbèidāo 直背刀, literally "straight sabre" or "straight-back sabre". The zhíbèidāo has the back of the blade completely straight, and the edge is straight practically in its entirety, except for the tip that curves to join the spine.

The straight sabre was the hand weapon par excellence in the military until the invasions of the Mongol tribes at the end of the Sòng 宋 dynasty, which carried curved sabres. From then on, the curved design of the blade was extended to virtually completely replace the straight sabre, which only survived among ethnic minorities in the west and southwest, such as the Tibetans.

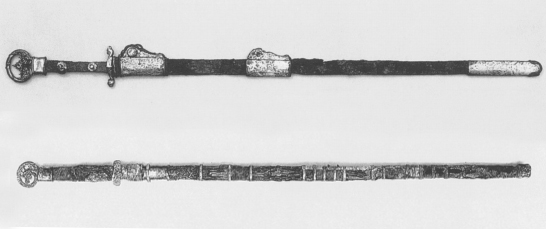

Two zhíbèidāo from the 7th century, 102.2 and 99.7 cm in total length.

Tibetan zhíbèidāo.

Yànmáodāo 雁毛刀 or “goose-quill sabre”

The influence of the Mongolian sabres resulted in the appearance, probably during the Sòng dynasty, of the yànmáodāo, a straight-blade sabre that curves slightly in its last quarter, towards its percussion centre. This design maintains cutting power while adding the ability to thrust.

This sabre is considered a transition between the straight sabre and the later more curved sabres, and was in use from the Míng 明 dynasty to the mid-Qīng dynasty 清.

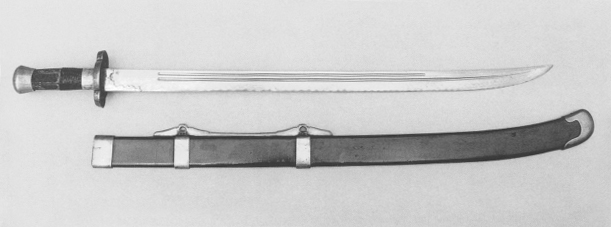

An 18th century yànmáodāo, 74.3 cm of blade length.

Centre of percussion

The centre of percussion of a sabre or sword is the point of the blade that transmits maximum power to the target in a slash. Impacting the target with the centre of percussion also means that the base, in this case the handle, does not move on impact, and therefore requires less cutting effort. Impacting beyond the percussion centre requires a firmer grip and, consequently, greater effort to control the handle and not drop the sabre from the hand on impact.

In the case of narrow-blade sabres, the percussion point is usually found where the last quarter of the blade begins, while in sabres whose blade widens as it approaches the tip, the centre of percussion is a wider area and is closer to the tip.

After the Yuán 元 dynasty, curved sabres became much more popular, and began to be referred as pèidāo 佩刀, which can be translated as "belt-worn sabre". These pèidāo ended up replacing the jiàn 劍 sword as a military hand weapon, because the amount of training required for the effective use of the sabre was much lower than that required for the jiàn .

The pèidāo

The term pèidāo 佩刀 originally refers to a curved sabre, and encompasses the following types: yànmáodāo, liǔyèdāo , piāndāo and niúwěidāo.

During the Qīng dynasty, however, the term pèidāo was used to designate all kinds of sabres which were single-edged for most of their length, without having to be curved, provided they were carried to the waist, so it was used as synonymous with yāodāo 腰刀, "waist sabre".

Liǔyèdāo 柳葉刀 or “willow-leaf sabre”

During the Míng and Qīng dynastes, the most common sabre was the liǔyèdāo, although the yànmáodāo continued to be in use for much of this period.

The liǔyèdāo is characterized by being curved along almost the entire length of its blade. This curve could be more or less deep. According to texts from the first half of the twentieth century, these sabres were also known as miáodāo 苗刀 or "sprout sabre", although this name today refers to a two-handed long sabre.

The liǔyèdāo became the hand weapon of choice for both infantry and cavalry.

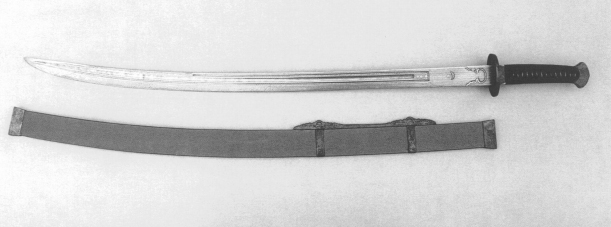

A 19th century liǔyèdāo.

The piāndāo 㓲刀 or “slicing sabre”

Also during the Míng dynasty, the piāndāo appeared, a less common type of sabre with a steep curve along its entire blade, especially suitable for short range combat. This type of sabre was probably inspired by Indian and Persian blades, and was mainly used in conjunction with a shield by military units specializing in skirmishes.

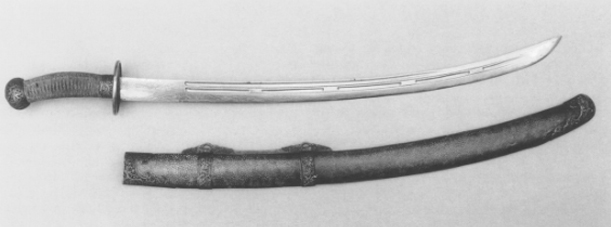

Piāndāo of the late nineteenth century.

The niúwěidāo 牛尾刀 or “ox-tail sabre”

Finally, in the nineteenth century, the niúwěidāo emerged, characterized by a heavy blade of moderate curve at the base, which becomes deeper as it approaches the tip, as well as wider and less thick at the tip. This design modifies the weight distribution and centre of percussion of the sabre, which is wider, and makes it ideal for cutting enemies without armour. For this reason this sabre was very popular among guerrillas and civilian militias of the late Qīng dynasty, when the armour was no more in use due to the proliferation of firearms.

After the fall of the Qīng dynasty, Chinese military sabres began to adopt the characteristics of European sabres. Therefore, the use of the niúwěidāo was limited to martial artists and rebels and yet because of this it is the only traditional Chinese sabre that continued in use after the fall of the last dynasty. This is the most common sabre used in martial arts today.

Two niúwěidāo from the late nineteenth century - early twentieth century.

There are also some types of traditional Chinese sabres that, although by the characteristics of their blade can be classified into the categories already named, we think they should be highlighted.

The chángdāo 長刀 or long sabre

The chángdāo is a long, two-handed sabre, for military use, with a slightly curved blade. The long sabre appeared during the Táng 唐 dynasty, as the military weapon of choice for vanguard infantry units. According to references of the time, it was composed of a blade of about one meter and a somewhat longer handle.

The chángdāo fell into disuse after the Táng dynasty until it appeared again in the Míng dynasty, with a different design: a blade almost two meters long with a handle of just over a third of the total length of the weapon. This made it such a long weapon that it took two moves, or the help of a companion, to unsheathe it. This chángdāo was used at the frontiers against Mongol troops, and bears much resemblance to Japanese swords, on which it seems to have been based on its design.

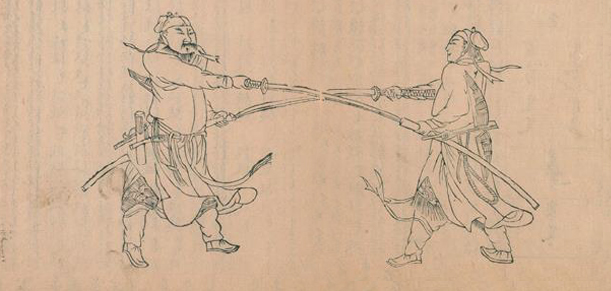

Assisted unsheathing of the chángdāo. Image taken from a long sabre manual from the late Míng dynasty.

The miáodāo 苗刀 or “sprout sabre”

The miáodāo is a non-military sabre used by guerrillas in the fight against japanese pirate incursions during the Míng dynasty. Its shape is similar to that of the chángdāo but of shorter length and, although it can be considered a descendant of it, it is also said to be based on the katanas carried by the Japanese. The guerrilla groups used it mainly to deal with their Japanese enemies.

The dàdāo 大刀 or big sabre

Another sabre used by guerrillas in the fight against the Japanese, in more recent times, was the dàdāo.

The dàdāo is characterized by a wide and sturdy blade, which can reach up to 90 centimeters in length, and a long handle, which made it possible to handle the weapon using either one or both hands, although this depended to a large extent on the weight of the weapon, which varied substantially between different models. The dàdāo has a weight distribution to the tip that gives it great cutting power, so it was a fairly effective weapon even in the hands of under-trained troops. That is why it was mainly used by guerrillas and paramilitary organizations, especially during the Second Sino-Japanese War (中国抗日战争 zhōngguó kàngrì zhànzhēng, 1937-1945), when civilian militias, which did not have firearms, were ambushed to attack Japanese soldiers by surprise and, armed with these sabres, could cut off the heads of enemy soldiers with a single cut.

Because of this, the dàdāo is also known as "anti-Japanese sabre" (抗日刀 kàngrì dāo).

A patriotic song of the time, the March of the Sabre (大刀進行曲 dà dāo jìn xíng qū), began with this line:

大刀向鬼子們的頭上砍去!

Dàdāo xiàng guǐzi men de tóu shàng kǎn qù!

Our dàdāo raised above the heads of the demons, cut them off!

Despite these facts, the dàdāo appears to have been, both in the last years of the empire and in the early days of the republican era and in the conflicts that followed, an instrument of terror used to keep the population under control, as well as for the execution of thugs or captured enemies.

Some dàdāo, probably of the twentieth century.