Introduction:

The Chinese conception of the afterlife has been gradually formed over centuries by mixing indigenous and foreign ideas, the latter coming from Indian Buddhism. Despite referring to the other world, these ideas profoundly affect the lives of the living and condition behaviours, rituals and daily festivities.

We have decided to divide this information into four articles, to make it more comfortable and digestible to read:

- The Realm of the Dead

- The Ten Kings of the Underworld

- The Violent Death or Death in Vain

- The River of Oblivion and Reincarnation

As we publish them, we will add links to each of them to make it easier to navigate between one and the others.

In this first article we will draw in general lines the structure of the Chinese cosmos, and we will describe the characteristics of the world of the dead, delving into the following articles in several more specific aspects.

Before we begin, it is important to emphasize that Chinese religions, unlike Western monotheisms, are not mutually exclusive. The practices and beliefs of Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism are mixed together forming, in what we can call the Chinese "folk religion", an amalgam sometimes chaotic but also very rich and complex.

In this popular religion, the different currents influence each other, share, exchange and "dialogue", sometimes with greater fluidity and others with a certain tension, reaching consensuses not explicitly formulated, which allow them to coexist in the thought and practices of the Chinese people.

Spirits, deities and ghosts:

When a person dies, he becomes a guǐ 鬼. Guǐ can be translated as ghost or even demon, but in this case, in order not to confuse it with the Western concept of ghost, it would be more appropriate to translate it simply as spirit. That is, guǐ is the spirit of a deceased person and, a priori, the term does not have a negative or frightening connotation, as the word ghost can have it in English.

When the soul of the deceased is appeased with offerings and regularly and duly cared for by his living descendants, it becomes an ancestral spirit, which is benevolent and treatable by the living, being able to help them at certain times.

Only when these spirits are not properly cared for, either because they have no descendants or because it has not been possible to properly comply with the mortuary rites, do they become what we in the West understand by ghosts: "solitary wild spirits" (gūhún yě guǐ 孤魂野鬼) or demons (shà 煞). These spirits roam the border between the world of the dead and that of the living causing problems in the latter.

Finally, the spirits of important characters, whose cult extends beyond one's own family, become deities (shén 神) or immortals (xiān 仙), and usually dwell in Heaven (Tiān 天).

The realm of the dead:

According to Chinese thought, the cosmos is made up of Heaven, Tiān 天, and Earth, Dì 地 (also referred to as Tiānxià 天下, that is, what is "under Heaven").

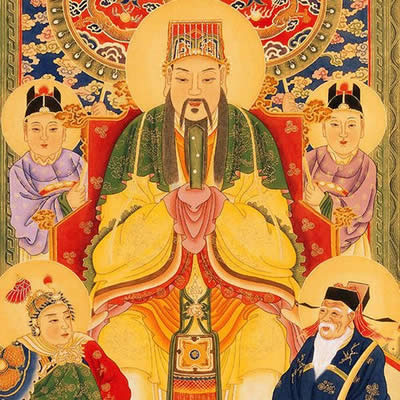

Heaven is inhabited by deities, spirits of immortals and important characters belonging to the three Chinese religions, and ruled by the Jade Emperor (Yù Dì 玉帝).

The Jade Emperor (Yù Dì 玉帝).

In turn, the Earth comprises the realm of the living or "regions of light" (yángjiān 陽間), where the Son of Heaven (Tiānzǐ天子, the name by which the Emperor of China was known) reigns, and the realm of the dead or "regions of darkness" (yīnjiān 陰間).

Other names by which the realm of the dead is known are Dìxià 地下, "under the Earth", Huángquán 黄泉, "the Yellow Springs", Yōumíng Shìjiè 幽冥世界 or, simply, Míngjiè 冥界, "World of Darkness".

Within the realm of the dead, built in the likeness of the world of the living, is the seat of government of the afterlife (陰曹地府 yīncáo dìfǔ), an idea that seems to be of autochthonous origin, and the Dìyù1 地獄 or "Earth Prison". This idea is of later Buddhist origin and is equivalent to the Sanskrit term naraka. Both places, yīncáo dìfǔ and Dìyù, coexist or even overlap in the popular imagination.

In the first and second centuries, when the idea of Dìyù appeared in China, it was placed on Mount Tàishān 泰山. The governor of this abode of the dead was considered the "Grandson of Heaven" (Tiānsūn 天孫), and was in charge of summoning the hún 魂 and pò 魄 of each person2. On Mount Tài the records with the years of life assigned to each living person were kept.

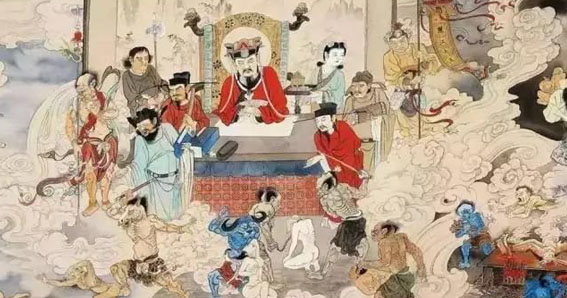

In Dìyù, souls are judged and punished for their actions in life, before obtaining a new incarnation according to the karma accumulated in their past existences. Dìyù consists of ten courts that judge souls and apply punishments, known as the Ten Courts of Yánluó (十殿閻羅 shí diàn Yánluó).

Thus, Dìyù is a kind of purgatory in which the souls of the dead are judged and punished, but not eternally. It is not a hell in the Christian sense of the word. All souls pass through Dìyù after death, and this fate is in no way the result of divine punishment.

We have already spoken on another occasion of the hún and pò, which are genuinely Chinese conceptions. Since the arrival of Buddhism in the country, ideas such as reincarnation and cyclical existence were introduced into the popular imagination, where they coexist with other seemingly opposed ideas.

According to the Buddhist conception, death is not a definitive change, but a part of a cyclical process of existence, death and rebirth. The Chinese afterlife evolved to integrate part of these ideas, combining those of local origin on ancestors with others of Buddhist origin on cyclical existence. The result is an Afterlife that is understood as a place of temporary residence, transition between the death of the individual and his next incarnation, but endowed with characteristics and attributes similar to those of the world of the living.

The yīnjiān, that is, the world of the dead or kingdom of darkness, is configured as the polar opposite and complementary to the yángjiān, the world of the living or region of light. In these terms, yīn 陰 and yáng 陽 not only refer to their literal meaning of dark and luminous, but act in their usual sense as a dichotomous pair.

This means that the yīn and the yáng world are relative to and reflect in each other. They are juxtaposed and in mutual interaction. A popular phrase says that "what separates yīn and yáng is as thin as a sheet of paper" (陰陽隔層紙 yīn yáng gé céng zhǐ).

The world of the dead is thus an imitation of the world of the living. In the popular imagination, the world of the dead is a more or less exact copy of the world of the living, with the same places and activities. Life after death thus continues with the daily life of the known world, resolving the anxiety of the human being for an unknown destiny after death.

The elaboration of this realm of darkness was progressive, and over the centuries it has inherited the characteristics of the realm of the living, including its bureaucratic system of administrative officers (府君 fǔjūn).

In the following article, we will examine in more detail the Ten Kings or Courts of the Underworld, and how this idea has progressively evolved until it was fully formed around the ninth century.

Notes:

1. Dìyù 地獄 normally refers to the purgatory through which the dead pass on their way to reincarnation, but it is also used to designate hells, one of the six kingdoms of Buddhist existence (liùqū 六趋 or liùdào 六道). In the latter case, it is also often referred to as shíbā dìyù 十八地獄, "eighteen earth prisons", since hells have eighteen levels. We use it here with the first meaning.

2. For more information on these concepts, see our article The Idea of Soul and the Veneration of Ancestors.