Introduction:

Although we have already spoken more or less extensively on other occasions about certain aspects or periods of the history of tea, we would now like to address this issue with a more global approach.

The history of tea and its culture is an extensive topic and impossible to cover in detail in one or several articles of this blog. Even the books that have been written about it often focus exclusively on certain eras. Thus, we do not intend to offer a detailed view of this whole long history, but a general outline in broad strokes.

Therefore, in the topics that we have already discussed previously we will not go into detail and we will refer the reader to some of our previous articles where you can find more information about it. These articles are:

- From «Eating Tea» to «Drinking Tea»: Tea Since Táng Dynasty

- Lu Yu and the Cha Jing (I): The Sage of Tea

- Lu Yu and the Cha Jing (II): The Classic of Tea

- The ‘Cha Jiu Lun’, A Debate Between Tea and Wine

- Cha Ma Dao: The Tea Horse Road

Origins of the tea plant:

All the tea comes from the plant called camellia sinensis, whose origin is located in the current Chinese province of Yúnnán 雲南. From this region it would spread over thousands and thousands of years to the regions of northeast India, Southeast Asia and the rest of mainland China, even being found on the island of Taiwan.

Leaf and flower of camellia sinensis, or tea plant.

In this process of expansion, the plant mutated and adapted to different conditions and habitats, giving rise to more than five hundred subspecies, which we can group into two large main groups: camellia sinensis sinensis and camellia sinensis assamica.

The plant presents a great variety of characteristics among these subspecies. Some are large-leaved trees that can reach more than 25 meters in height, while others are small-leaved low shrubs.

The tea tree is a particularly long-lived plant. In Yúnnán there are tea forests of great antiquity. It is estimated that one of the oldest trees still alive is around 2700 years old.

Tea tree.

The chemical components of the tea leaf, among which we find catechins and other polyphenols, sugars, vitamins, amino acids, probiotics, oils, minerals, alkaloids, fiber and organic acid, endow the plant with medicinal properties highly appreciated by humans since ancient times.

The Chinese have been exploiting this plant for several thousand years, in various ways, which have been changing throughout history, some of them very different from what we recognize today as tea. In addition, they have developed a whole culture around this plant and its consumption, to the point that today drinking tea is undoubtedly one of the defining features of Chinese culture.

First uses of tea:

Legends attribute the discovery of tea to the mythical emperor Shénnóng 神農, the divine farmer, a figure linked to medicine, who is said to have taught humanity to sow and harvest grain and who tested all plant species to know whether or not they were suitable for human consumption.

Shénnóng 神農.

Regarding tea, the well-known "Shénnóng myth" tells that on one occasion, while this character was sitting under a tea tree, and feeling sick after having consumed a toxic plant, a leaf of the tree fell into the pot where he was boiling water. After drinking this water, Shénnóng felt revitalized and thus discovered the beneficial properties of tea.

We have already seen above that the first written reference to the Shénnóng myth appears in the Chá Jīng 茶經 of Lù Yǔ 陸羽 and that, therefore, he may have been the creator of such a myth, clearly false (see Lù Yǔ and Chá Jīng II: the Classic of Tea). Although some scholars believe that Shénnóng may actually be the name of a tribe or group of people (Shénnóng shì 神農氏), the myth is interesting because it tells us about an origin of tea as medicine.

The first consumption of the tea leaf seems to have been as an edible, possibly for medicinal purposes, in the form of pickles, fries or condiments. Certain ethnic groups in the Yúnnán region still consume tea in this form to this day.

Also, in some areas of Guǎngdōng 廣東 and Taiwan the Hakka (kèjiā 客家) groups still consume a kind of soup made with tea known as léi chá 擂茶, "crushed tea", to which nuts and cereals are added. The ingredients are ground in a mortar to form a sticky paste to which hot water is added, and the result is consumed as a soup. These forms of tea as an edible are very old and predate the use of tea as a beverage.

Preparation of léi chá 擂茶, “crushed tea”.

Due to the vague nomenclature with which the ancient Chinese referred to the tea plant, it is difficult to trace its origins. For a long time, there was no word to refer to this plant exclusively. The Chinese included it among a group of bitter plants that they named tú 荼, so when we find this term in written documents we cannot be sure that it refers to tea. Only from the Táng 唐 dynasty, when the specific term by which we know it today, chá 茶, would appear, does the information begin to be truly reliable.

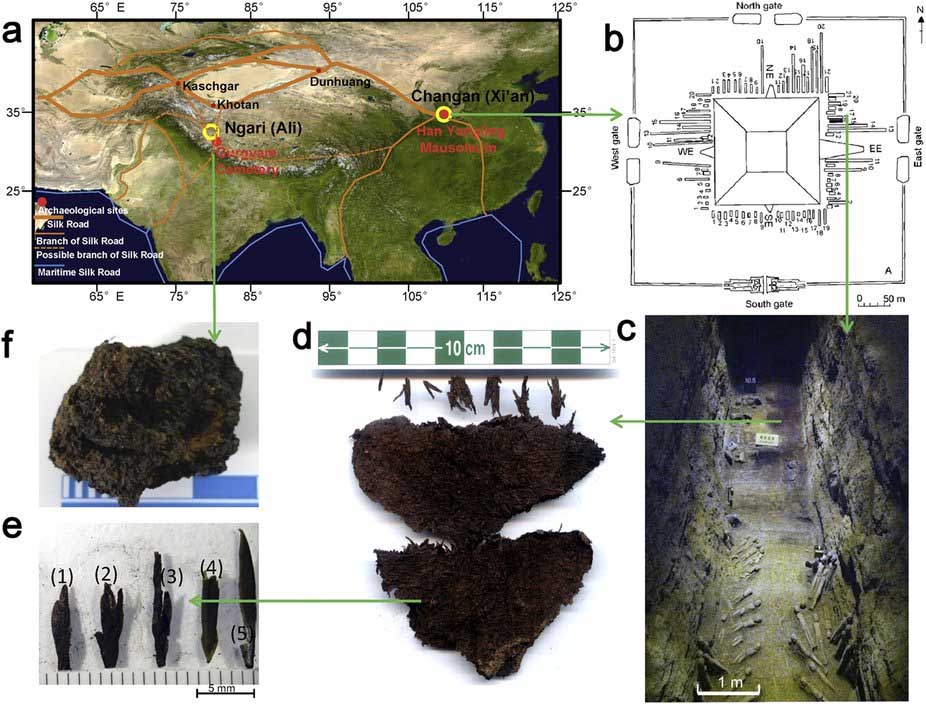

Although tea began as a product consumed locally in the producing regions, tea leaves have recently been discovered in the tomb of Emperor Hàn Jǐngdì 漢景帝 (died 141 BC), in present-day Xī'ān 西安. Chemical analyses confirm that it is camellia sinensis. This shows that tea was already being imported into this region in the second century BC. To preserve and transport these leaves without spoiling them, it is possible that the locals let them dry in the sun.

Similar findings speak of a transport of tea to the Tibet region as early as the second century AD, hundreds of years before written documents recorded tea trade with Tibet. Also, the fact that the emperors were buried with it, shows the importance that this plant had for them.

Findings of tea at the tomb of Emperor Hàn Jǐngdì 漢景帝 and in Tibet.

Although the leaves found in these tombs are composed of young buds of a fine harvest that point to a high degree of specialization and knowledge for the time, this does not mean that the tea was already consumed as a beverage.

Despite these recent discoveries demonstrating its consumption by some emperors and kings and, possibly, by other members of the elite, it appears that tea consumption remained limited mainly to the southern regions.

Wú Lǐzhēn

It is said that the first person to domesticate the tea plant was a monk named Wú Lǐzhēn 吳理真, a native of Yǎ'ān 雅安 in Sìchuān 四川. In the first century BC, Wú Lǐzhēn, aware of the medicinal properties of tea, would have taken seeds from wild tea plants growing in the mountains and planted and cultivated them himself.

Statue of Wú Lǐzhēn 吳理真.

Wú Lǐzhēn is said to have planted seven tea bushes on Mount Méngdǐng 蒙頂 of the Méngshān 蒙山 region and experimented with their cultivation. He is considered the father or ancestor of tea (chá zǔ 茶祖). However, its existence is questioned by many, and it could be another legend.

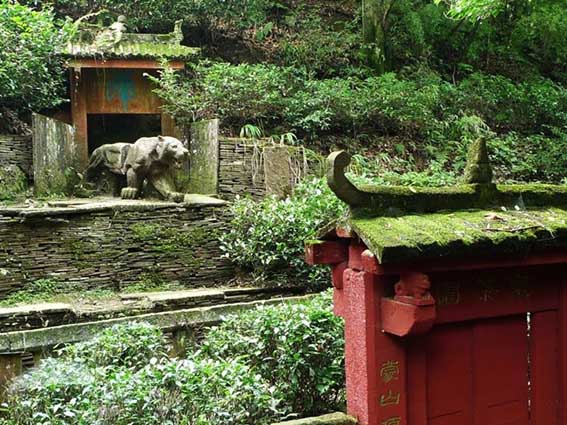

During the Sòng 宋, the place where this monk supposedly planted tea was an imperial garden (皇茶園 Huáng cháyuán) that supplied tribute tea (gòng chá 貢茶), and was protected under penalty of death. Although this garden still exists today, the plants that grow there are not the original ones planted by Wú, if they ever existed.

Imperial garden of Méngdǐng 蒙頂 where Wú Lǐzhēn supposedly planted tea for the first time.

During the Hàn 漢 dynasty, some medical treatises, such as the Shí Lùn 食論 by Huà Tuó 華佗 (year 220), contain references to what could be tea, but due to the nomenclature problem we have already talked about, we cannot be hundred percent sure.

By the third century AD, tea was already grown in the southwestern regions, in present-day Yúnnán and Sìchuān. Its consumption would have been reserved at first for emperors and social elites, with a high purchasing power.

After the fall of the Hàn dynasty, invasions by nomadic peoples in northern China produced large population shifts to the south. With these migrations, the center of China's culture also shifted, with southern traditions gaining greater prominence, tea consumption among them.

The domestication of the plant and its production allowed a surplus of product that was exported to new markets. It was around this time, around the fourth century, that tea consumption began to spread among ordinary people in southern China. Production and processing were refined and product quality improved, preparing for the big changes that were to take place during Táng.

By the middle of the sixth century there was already a general understanding of the tea plant and its medicinal properties, although a specific terminology had not yet been developed to refer to it.

Already at this time tea was consumed in the form called jiānchá 煎茶, cooked in water with other ingredients such as chives, ginger, orange peel, butter and salt, which was to be the predominant form during the Táng.

The spread of tea consumption before Táng

In order to transport tea over long distances without suffering great deterioration, certain changes in its processing would have been necessary. Before, probably an unprocessed leaf would have been collected and consumed nearby, perhaps being dried in the sun to keep it for longer time.

However, faced with the need for a stable product, which could be transported and consumed at other times and places, tea cakes or medallions appeared. This was made possible by the discovery of the deactivation of the enzymes that produce oxidation by applying heat in the form of steam, so that the tea remains green for longer.

It is not clear at what point, before Táng, these cakes begin to be produced with steamed leaves, ground and pressed in a mold along with some binding substance. This change would have allowed transport over long distances without the tea spoiling along the way.

For many centuries all that had been produced was green tea (lǜchá 綠茶), the rest of the current varieties still unknown. But by this time post-fermented tea (hēichá 黑茶, although this nomenclature is later) would have appeared, when tea blocks fermented by accident during transportation. It turned out that this tea, which at first seemed to have spoiled, became softer and acquired greater complexity of flavour.

To be continued...

In the following article we will explore the great changes that occurred during the Táng, both materially and philosophically.