This article is a continuation of History of Tea and its Culture (I): First Uses of Tea.

Tea culture in the Táng dynasty

The Táng 唐 dynasty (618-907) was the time of greatest diffusion of tea consumption within China, and in it there were great changes that defined not only the way of consuming tea, which would continue to change over time, but also the way of thinking about it during the rest of China's history.

Certain economic changes made these processes possible. The subsistence economy, in which families produced for their own consumption, gave way to commercial agriculture, allowing producers to sell their product on an open market, and the diffusion of certain products away from their origin.

A more prosperous economy meant that more people had money to buy this exotic herb; likewise, the unity of the territory and the improvement of infrastructures and communication routes facilitated the transport of tea to the north.

By the middle of the eighth century, tea was already drunk by people from all walks of life, although within high society a high degree of refinement and specialized knowledge developed that became a mark of social status. The tea market spread from common types of tea for mass consumption to some high-quality products whose market was a luxury clientele.

It was at this time that the word chá 茶 appeared, a term that is still valid today to unequivocally designate the camellia sinensis plant, and that derives from the old character tú 荼. Other names of the plant continued in use, such as míng 茗, used to refer to tea in materia medica, and which remained even after chá became the standard term.

Other than that, already in the middle of Táng we have evidence of the existence of tea houses, spaces dedicated especially to this drink, which accounts for its diffusion among the general population.

In terms of cultivation, farmers adapted the plant by hybridization to colder climates in the north, and began a time of research and experimentation with the plant that led to the emergence of new varieties.

Lù Yǔ

Lù Yǔ

The most important figure of this period in relation to tea is undoubtedly Lù Yǔ 陸羽, a scholar who dedicated much of his life to research on this plant, and author of the first and most important treatise on it: the Chá Jīng 茶經 or Classic of Tea (we have already talked about Lù Yǔ on other occasions so we will not expand here on him and we refer the reader to our previous articles: Life of Lù Yǔ; Chá Jīng).

For several centuries, the imperial court needed a series of luxury products that were not obtainable on the open market, and whose production they had to take care of. During Táng, obtaining these items had evolved into a complex tribute system (gòngxiàn 貢獻), whereby special items such as medicines, food, textiles, animals, handicrafts, etc. were procured.

Under the tribute system, each region provided the imperial court with local specialties. Sometimes government officials procured products in the markets and sent them to the court, but often they oversaw production directly to ensure the best quality of the product in question. Tea, as a luxury product consumed by emperors and the royal family, was also introduced into the tribute system, giving rise to what is called "tribute tea" (góngchá 貢茶).

The state needed enormous quantities of this product of the best quality, which the open market could not provide with uniform quality. Thus, the best teas became a state monopoly, and official posts were established to oversee the cultivation and processing of tribute tea.

Government officials thus began to supervise production on plantations that produced tea, sometimes exclusively, for the imperial court. The first of these tribute tea factories was established in Zhèjiāng 浙江 province in 770.

By the end of the ninth century, tea had grown from a regional specialty of southern China to an essential component of the daily life and economy of the empire.

Tea as a gift

Tribute tea became a standard gift from the emperor to his favourite subjects and thus an instrument for strengthening both social and political ties. Such was the value of tea that, implicitly, the recipient of the gift was expected to reciprocate with his loyalty to the monarch.

This system of gifts existed since ancient times, when it served to establish alliances in times when there were no strong institutions. However, and despite the evolution of government institutions, the custom of granting gifts remained in time, as a sign of the emotional factor in power relations.

The tribute tea given by the emperor (cìchá 賜茶) to one of his subjects represented imperial favour, and greatly increased the prestige of the recipient while extolling the public image of the sovereign by making him appear generous to his subjects. Due to tea's role as a socializing drink, there were numerous occasions to show the gift received from the emperor.

Tea was also considered an ideal gift for other foreign monarchs. This not only extolled the receiver as a symbol of appreciation for the Táng emperor, but also expanded China's sphere of cultural influence, drawing foreign elites into their own culture. This custom of giving tea to the rulers of foreign nations continued for centuries, to such an extent that during the Míng 明 dynasty (1368-1644), when these gifts were given to Tibetan religious authorities, this custom was called "using tea to control the barbarians" (yǐ chá yù fān 以茶馭番).

But in addition to this tribute tea, quality tea also became a standard gift among people belonging to other social strata, and it became frequent to exchange tea gifts between friends. The gift socially elevated the donor demonstrating his good taste.

Along with these economic changes, other philosophical changes took place. A very high philosophy began to develop around tea, to the point of imagining tea as a spiritual path (dào 道).

The first recorded mention of this Way of Tea (chádào 茶道) appears in a poem by the monk and poet Jiǎorán 皎然, a friend of Lù Yǔ and one of the most influential figures of his time, who perhaps coined the term himself. This association of tea with a spiritual path implied that this drink possessed morally and spiritually elevated qualities, and therefore its consumption was no longer a daily action but something much more significant and profound.

Jiǎorán 皎然 seems to have been the first to associate a spiritual path (dào 道) with tea.

Jiǎorán and Lù Yǔ inaugurated an era of exploration of the moral dimension of tea. Tea was also patronized by Buddhist institutions, whose monasteries, often located in remote mountainous regions where tea grew naturally, were often responsible for the cultivation and processing of this plant.

In addition to its medicinal qualities, tea favoured meditation, keeping the mind awake and providing a sense of calm, which made it a favourite drink for the monks, who were also forbidden to drink alcohol.

Until the Táng dynasty, alcoholic beverages such as wine and other liquors (jiǔ酒) had been the socializing drinks par excellence, also playing a fundamental role in ritual, guarantor of the order of Chinese society.

But tea not only came into direct competition with alcoholic beverages in Chinese society, but also among the nomadic peoples of the north, who consumed fermented milk drinks such as kumis. And in addition to competing with alcohol, tea had to make its way into the market among other medicinal and tonic products such as ginseng and astragalus.

The nomadic peoples of the steppes of Mongolia and Central Asia consume an alcoholic beverage called kumis,

made from fermented milk.

Buddhist institutions modified their discourse from an exposition of the negative effects of wine to an exaltation of the qualities of tea. Progressively, there was a cultural change in the society from alcohol towards tea, which also assumed part of the ritual function that until then was carried by wine. Tea could now be used as a funeral offering, could nourish the dead and be offered to quench the thirst of pilgrims. And besides, unlike wine, it could be offered to the Buddhas.

A ninth-century satirical text, the Chá Jiǔ Lùn 茶酒論 (Discourse on Tea and Wine), found in Dūnhuáng 敦煌, gives an idea of this situation. We refer the reader to our article on this text for more information about it (The 'Chá Jiǔ Lùn', a Debate Between Tea and Wine).

Tea in ritual

Since the Shāng 商 dynasty, alcohol had played an essential role in official state rites, which purported to establish a connection between the emperor and the supernatural, and finally defining the emperor as the Son of Heaven (Tiānzǐ天子).

During the Táng dynasty, the shift of alcohol in favour of tea was also evident in state rituals. If until then tea had been considered a humble beverage, its use in these rites instead of wine substantially raised its status, making it a valuable instrument for sanctifying political power.

However, the ritual or sacrificial use of tea may have first appeared at the domestic level, as an offering to the ancestors of the family lineage, and from there have moved to the scope of the State.

In addition to being consumed as a stimulant by Buddhist monks, and as a medicinal plant, tea soon began to be drunk for mere pleasure. Lù Yǔ was one of the most influential figures in this change. In the Chá Jīng, Lù Yǔ considers medicinal preparations with other ingredients as disgusting, and advocates tea consumption with no ingredients other than a pinch of salt.

The predominant way of preparing tea in Táng was the so-called jiānchá 煎茶, which consisted of a tea soup with other condiments such as chives, ginger, orange peel and salt. Lù Yǔ also used this method, boiling it with a rich foam on top, but suppressed the rest of the ingredients.

However, jiānchá was not the only way to prepare tea. The humblest people simply added the leaves to hot water, similar to how tea is consumed today. It also appears that a prototype diǎnchá 點茶 ("whisked tea") was already brewed, although it would not reach its final form until the Sòng 宋 dynasty.

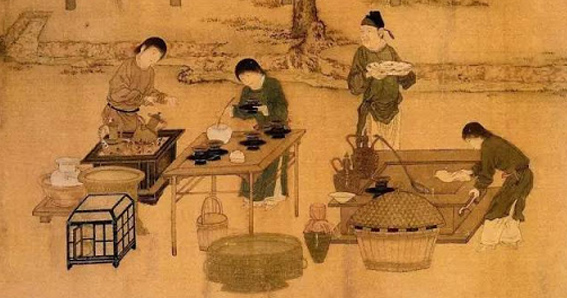

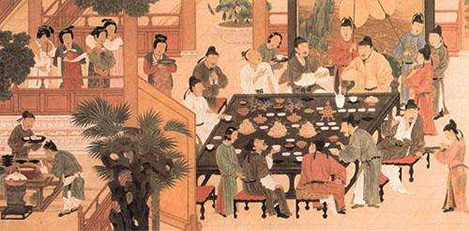

The preparation and consumption of tea restructured social life in China. Group gatherings to drink tea away from home became more frequent until they became a social habit.

Although tea drinking could be informal, gatherings between men of different social statuses were highly ritualized and required a certain etiquette. Buddhist monasteries were the first to encode this etiquette in the very texts in which monastic behavior was prescribed. These codes of etiquette are the prelude to the tea ceremonies (chálǐ茶禮) that would later appear described in the monastic codes of the Sòng dynasty.

The imperial court drank tea in a solemn and ritualized manner. Lavish tableware of precious metals made by the best craftsmen was used, and the servants prepared the tea in a ritual and laborious way.

Ordinary people drank more humbly. Lù Yǔ renounced lavishness and promoted a simpler and more modest way of preparing tea. Although he did not alter the mechanics or the process of tea preparation, he did propose a new mental attitude towards it, turning the preparation and consumption of tea into a practice of internal cultivation, an attitude that was also adopted by other characters in his closest circle, such as the monk Jiǎorán.

Writers and poets contributed significantly to imbuing tea with a new meaning outside everyday life. Tea was presented as a mediator between the human world and the supernatural, and as possessing high values. The tea literature produced during Táng associated it with the inspiration to compose poetry and the mental clarity needed to meditate. Buddhism and tea soon became linked in the popular imagination, and tea and Chán 禪 (Zen) became almost synonymous, as shown by the famous saying chá Chán yīwèi 茶禪一味 ("tea and Chán have a single flavour"), attributed to Chán master Zhàozhōu Cōngshěn 趙州從諗.

Chá Chán yīwèi 茶禪一味 (“tea and Chán have a single flavour”)

Poetry was the most prestigious and well-regarded form of cultural expression during the Táng, and thus came to greatly influence the attitude of the population towards tea. Poets introduced this drink as a literary topic, and when literati exchanged gifts of tea, they used to write poems to thank each other. Even so, poetry devoted to tea is only a minor genre of all the poetry produced in Táng times.

Tea ware

Until then, while tea had been a medicinal preparation and an edible, people prepared it on the same tableware used to make soups and meals. As tea became a form of aesthetic expression and good taste, the tableware used in its preparation was changing, reflecting not only practicality but also aesthetics.

Many of the new designs appeared in response to the problems of tea preparation, such as the need for servants to transport hot containers from the fire to the table.

In the imperial court, pieces forged in gold or silver were preferred. However, most consumers used ceramics of different styles, such as Yuè pottery (越窯 Yuè yáo) of celadon, Tóngguān pottery of Chángshā (長沙銅官窯遺址 Chángshā Tóngguānyáo Yízhǐ) or Dìng porcelain (定瓷 Dìngcí).

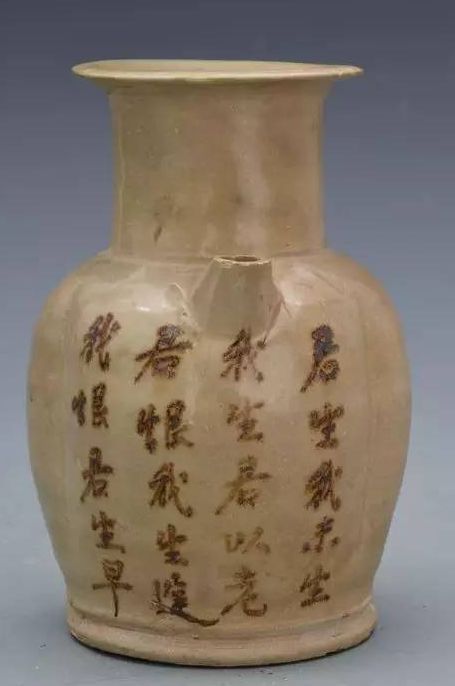

Chángshā Tóngguān pottery:

Characterized by its grayish-green enamel, Tóngguān pottery produced everything from figures to utilitarian objects such as bowls, jugs and other tableware. The objects were decorated with paintings of figures, natural motifs or calligraphy, before applying enamel, which in its time was an innovation since it managed to protect this decoration so that it did not deteriorate with use.

This style of ceramics had its peak towards the end of Táng and declined after.

Chángshā Tongguān ceramic (長沙銅官窯遺址 Chángshā Tóngguānyáo Yízhǐ) jar.

Dìng porcelain:

Produced in Dìngzhōu 定州 in Héběi 河北, it was characterized by objects generally of a white or grayish colour with an almost transparent enamel, and usually decorated with reliefs. This pottery continued to be produced until the Yuán 元 Dynasty.

Dìng porcelain (定瓷 Dìngcí).

To be continued...

In the next article we will deal with tea culture during the Sòng, the time of greatest sophistication and refinement in tea consumption.