Introduction

Corruption was a widespread problem during the Qīng 清 dynasty. Such was its magnitude that it precipitated the fall of the dynasty. Corruption has often been cited as the underlying cause of the uprisings and rebellions that arose during the nineteenth century, as well as justification for the activities of secret societies and certain martial arts circles in their supposed struggle against the government. In this context, it is, to some extent, a justification for Chinese nationalism, which despises the Manchus as foreign barbarians and extols the superiority of the Han 漢 ethnic group.

In Southern China's martial arts circles, such as Hung Ga Kyun 洪家拳, Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 or Wing Chun 詠春, corruption would have been the justification for proclaiming the famous Fǎn Qīng fù Míng 反清復明 ("Expel the Qīng and Restore the Míng"). We have already talked on other occasions (Secret Societies and the Origin of Triads) about how this motto was created a posteriori by secret societies and illegal groups. In this article we want to expose the real problem of corruption: its magnitude, its causes, and the measures that were taken to deal with it, as well as examine in particular what is possibly the most famous case of corruption: the case of Héshēn 和珅 towards the end of the reign of Qiánlóng 乾隆.

For this we will rely on the studies of Nancy E. Park and Chong-chor Lau & Rance P.L. Lee, who have studied corruption in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, respectively, as well as the studies of Shawn Ni & Pham Hoang Van and Wook Yoon, cited below in the "Sources" section.

Definition of corruption

The first problem we deal with is that of defining what was considered corruption, since this is a flexible concept, which could be interpreted differently according to different customs, ethics and a sense of pragmatism, and what was interpreted as corruption by the government did not necessarily correspond exactly to what was interpreted as such by the commoners.

The Qīng government understood corruption as the misappropriation of public funds and provisions, as well as the use of power for personal gain. This definition fell within the illegal acts classified as sīzuì 私罪 (private crimes); in contrast to those classified as gōngzuì 公罪 (public crimes), which were acts committed during the professional exercise of an official, but considered unintentional (negligence) and that did not seek personal gain.

Thus, acts of corruption were those committed by government officials that implied an intention of personal benefit.

Acts of corruption, in turn, can be classified into those directed at the government —embezzlement of funds for public works, military funds, and public property; minting of counterfeit money, etc.— and those directed at the people —earnings by improper performance of official duties, extortion by creation of new fees or taxes, collection of irregular taxes, acceptance or demand of bribes in exchange for favours, allowing family members or subordinates to demand undue fees, extorting money by torturing criminal suspects.

Due to the structure of the imperial bureaucracy, corruption directed at the people was the most widespread (63% of cases during the nineteenth century), despite being the harshest punished, and was concentrated at the lowest level of the imperial bureaucracy.

Of all the provincial, prefectural and district magistrates, the latter were the most often punished for corruption, probably because they had more direct contact with the local people.

A problem of definition: gifts

The custom, common in China, of offering and exchanging gifts is an added problem when it comes to determining certain corrupt acts.

Gifts (kuì 饋) played an essential role in Chinese culture since ancient times. It was common, therefore, to give gifts to commemorate the birthday of a superior, the appointment to a new position, an official visit or certain festivities.

Differentiating what was a gift and what was a bribe (lù 賂) was not clear and simple. Often, this distinction was arbitrary and appears to have been based on subjective perceptions rather than objective criteria. Gifts, though made sincerely, could potentially corrupt the recipients and influence their decisions.

For this reason, Manchu emperors tried to limit the practice of giving gifts, on the one hand, by setting limits on the value or type of goods that could be received and, on the other, by forbidding magistrates and prefects to visit their superiors except on official business.

However, the exchange of gifts and favours was often an expression of respect and friendship and served to cement a complex social network of reciprocal obligations. In many cases, then, what was considered by law to be an illicit exchange could be considered appropriate according to social norms and permitted within the culture of government.

We are therefore faced with a dilemma when it comes to considering what is a bribe and what is a licit gift, since, between the two extremes, there is a whole ambiguous continuum subject to subjective interpretations. We find evidence of this ambiguity in the contradictory views expressed in official commentaries, imperial edicts, and judgments of magistrates.

Causes of corruption:

Despite being harshly punished, corruption flourished in every corner of the empire during the Qing dynasty, although, as we will see later, the root of the problem came from earlier times.

Low salaries

Most studies on corruption in this period agree in identifying the main cause of the problem: the salaries of civil servants were generally too low. Not only that, but an official also had to incur a series of expenses to administer his position, expenses that he was expected to assume out of his own pocket.

For example, a district magistrate had to hire several personal secretaries (mùyǒu 幕友), whose salaries he had to pay himself. He was also in charge of several employees or government clerks (shūlì 書吏) who, although they received their salary from the administration, received such a miserable payment that they were often unable to meet their most basic needs of food for themselves; much less for their families.

Therefore, if the magistrate wanted to maintain his administration in an honest manner, he had to subsidize his employees from his own pay. Thus, the total expense needed to run his post was much greater than his legal income. Although, as we will see a little later, there was other legal sources of income in addition to the regular salary, this ammount was still generally insufficient.

Origin of the reduction in salaries:

The problem of low salaries of civil servants was not unique to the Qīng dynasty. This problem would have originated at the beginning of Míng 明 as a result of the economic pressure caused, among other causes, by the increase in population.

Government salaries were progressively reduced throughout the Míng dynasty to the point that, by the middle of the fifteenth century, half of the salaries went unpaid. Corruption was already a serious problem in this period. The Manchus inherited this situation and, when they took power, avoided major institutional reforms, particularly in the area of taxation, so wages remained low at first.

More than six hundred years earlier, officials of the Sòng 宋 dynasty were paid much higher salaries than during Míng-Qīng. Current studies indicate that an effective wage reform would have been feasible by the middle of the Míng period, but by the time the Qīng state attempted to implement it in the mid-dynasty, the magnitude required for such a reform to be effective made it unfeasible.

In this way, the state depended on extralegal sources of income to be able to function. One of these sources of revenue was the levying of irregular taxes known as lòuguī 陋規 (literally, "reprehensible practices"). These funds were regularly collected from the local population by an authority figure, in addition to the taxes established by law. Although they were illicit, the population often accepted them because it was understood that without them government officials could not carry out their administrative duties.

The amount of these irregular taxes was not formally established, but was regulated by local custom. As long as the amounts collected remained within the usual limits, the population tolerated them. If an official exceeded his demand, he risked provoking local revolts and uprisings.

Here, then, we have a new problem in identifying corruption. When was the levying of irregular taxes an inevitable and necessary practice to make the administration function, and when was it led by interests of personal gain? The perception on the part of the authorities did not necessarily matched the perception of the people who paid these fees.

Social pressures

Furthermore, in order to become a civil servant, large sums of money had to be invested, which in most cases had been loaned, and had to be returned. The two ways of access to the civil service were the imperial examinations and the purchase of the post. The latter possibility had been established with the intention of increasing the state's revenues. On the other hand, the exam required years, even decades, of preparation and study, and if it was passed —only a few among tens of thousands did pass it—, it could again take years before a position was given and assumed.

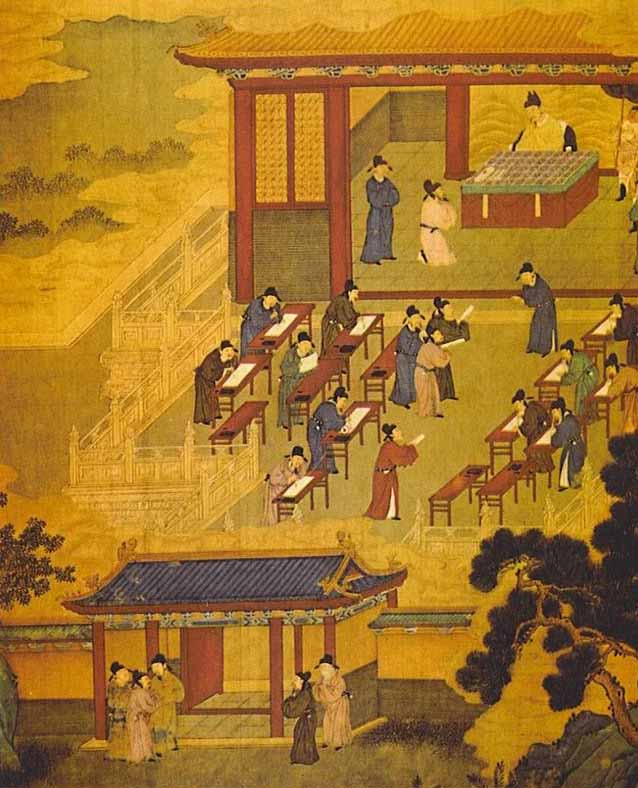

Examinations for access to the civil service.

Thus, in one way or another, when an official took office he had probably accumulated large debts to those who had supported him, which he was expected to pay off promptly, or else he would carry a significant social stigma. But, if it depended on his regular salary, it could take many years to comply.

But if these pressures were not enough, there were other related to the standard of living expected of civil servants, who belonged to the highest social class, consuming high-quality products and offering generous gifts, contributing to public charities or subsidizing projects in their home communities, entertaining their superiors, and helping friends and relatives.

Concentration of power

Low salaries and administrative expenses alone were not sufficient cause for sustained corruption on a large scale. What made corruption possible was the combination of low salaries and concentration of power in the hands of officials, who served as tax collectors and judges in local courts as well as administrators of public affairs.

This multiplicity of roles made it difficult to control their power and invalidated some of the mechanisms for preventing corruption.

Dependence on government clerks

Finally, another cause of corruption was the dependence that officials had on government clerks. This was because officials were transferred to different locations at most every three years, precisely to avoid corruption, with the intention of preventing them from developing close ties with the local population that could affect their decisions.

It was therefore these clerks of the local government, who were permanently linked to the ministry, who had better knowledge of local affairs. They also had specialized knowledge, as opposed to the general scholarship —history, literature, knowledge of the Confucian classics— that magistrates acquired in preparation for imperial examinations, and they were responsible for performing a number of administrative tasks that the official in charge simply could not cover.

Because of this dependency, clerks were often in a position to sabotage the policies of magistrates and to blackmail local people. They were often allowed and even asked to collect irregular taxes from the population or from lower-level officials, from which they gave an agreed part to their superior and kept another for themselves.

As we have seen, the collection of irregular taxes was governed by local customs. A government official was therefore not to allow his secretaries to collect taxes beyond the usual limits, but these were often exceeded.

Thus we see that the bureaucratic structure itself led more or less inevitably to corrupt practices.

Measures and punishments:

Corruption was so widespread that it greatly worried emperors and high-ranking officials, and a number of preventive and punishing measures were arranged to prevent it.

Prevention measures

The first way in which corruption was expected to be avoided was through the moral education that candidates for the imperial examinations received. After years of Confucian education in the values of a good ruler, the aspirant had to at least know and respect moral norms. However, most officials found the reality so different that they took these ideas simply as something to expand on in exams, with little practical application in real life.

Somewhat more pragmatically, there was a system of responsibilities, whereby a superior was to supervise his subordinates in the performance of their duties, and to prosecute and report any improper action, and to be held responsible for the faults of those in his charge. He also had to give an account of his own obligations to his superiors.

However, due to the need to find funding outside the law, the accountability system often led to the development of organized corruption networks involving officials of various ranks. Thus, when an official demanded improper payments from his subordinates, he had to agree to cover up their misdeeds.

On the other hand, there was the rule of avoidance of the natal district and that of periodic transfer. The first stipulated that an official could not be elected to office in his home district, to avoid being subjected to social pressures to favour friends and relatives. For this very reason, he could not marry a woman from the district in which he served.

The rule of periodic transfer, which we have already mentioned, dictated that an official could not remain in the same post for more than three years, and must be transferred to another place at the end of that period, to avoid developing close relations with local inhabitants that would compromise his impartiality. Despite the three-year limit, the average duration of a position was around two years.

Finally, and taking into account the need for a realistic salary, a series of measures were taken to increase the legal income of civil servants.

In this regard, Emperor Yōngzhèng 雍正 implemented the system of yǎnglián 養廉, a supplementary salary that in theory was supposed to serve to motivate the integrity of officials. The yǎnglián was a much higher income than the regular salary (fènglù 俸祿). For example, the regular salary of a district official in Jiāngsū 江苏 in 1851 was 45 silver taels per year, while his yǎnglián could be as high as 1,800 taels.

The amount of yǎnglián was not regular, and depended on the specific position rather than on the rank of the position. In addition, part of the sum was paid in kind or could be withheld as a mandatory contribution to public needs. In addition to the yǎnglián, magistrates could also receive a certain amount of government funds for administrative expenses (gōngfèi 公費).

In addition to being intended to prevent corruption, the rules of avoidance of the home district and periodic transfer also prevented the formation of connections that could be used to lead riots or revolts against imperial authority. However, and as we have already mentioned, they in fact caused the dependence of officials on clerks, a dependence that ended up favouring corruption.

Nor were the measures aimed at increasing revenues effective because, as we will see below, there was much more to be gained by being corrupt than by being honest.

The system of punishments

The punishment system, insofar as it was intended to discourage corrupt practices, was in itself a preventive measure.

In general, the law was harsh on corruption, which it punished more severely than other crimes. Likewise, corrupt acts directed at the people received greater punishments than those directed at the government itself.

In addition to administrative sanctions —fines, reduction of salary, reduction of category or rank, transfer, or dismissal— corruption also entailed harsh criminal punishments, ranging from twenty lashes with a bamboo pole to death by strangulation, including imprisonment or exile.

The harshness of the penalties meant that pocketing relatively small amounts of money was not worth it. For example, receiving fifteen taels of silver in exchange for illegitimate favours carried a penalty of between seventy and one hundred blows with a heavy bamboo stick. This amount of blows could easily kill anyone; therefore, it was not a much better punishment than death by strangulation, stipulated for those who received more than eighty taels in exchange for favours. This regulation meant that, if an official risked taking money from corrupt practices, he always tried to get as much as possible.

To report corruption, anyone could submit a letter reporting the unlawful acts of an official to the district government offices (yámén 衙門). Whether the local government did not investigate the case, or if the complainant was not satisfied with the trial, the plaintiff could go to the provincial authorities and even the national authorities.

However, the complainant was taking considerable risks in initiating legal proceedings against an official. Although law was the same for everyone, it was not applied in the same way and tended to favour the richest. A poor, low-social plaintiff who was not well connected did not have much chance of satisfying his interests as a claimant. Moreover, both plaintiffs and defendants could be interrogated under torture, and the interrogator would not miss an opportunity to extort money from both for profit, no doubt favouring whoever could pay the most.

In this way, most people generally tolerated government corruption, and only risked filing complaints when their survival was at stake.

On the other hand, we find in the enforcement of penalties the same problems that we find when defining corruption. For example, the collection of irregular taxes was generally an administrative necessity, and was accompanied by subtle forms of intimidation, making it difficult to differentiate from extortion for personal gain, which was punishable by immediate beheading. Whether the collection of these taxes could be considered extortion depended on particular circumstances, such as the amounts demanded or the purposes for which they were collected.

As a result, there was considerable flexibility in the application of the law, and many cases were tolerated, although they did not have the approval of the government. Thus, the anti-corruption law appears to have been applied arbitrarily, following subjective criteria of a political nature rather than objective criteria. In short, if the law had been applied to the letter, most officials would have deserved the death penalty. Those who were convicted were usually under investigation for other crimes, and received swift and harsh punishments. The government thus used the anti-corruption law as a political weapon and, as we will see later, political rivalries to control corruption.

In short, punishment measures imposed on corruption crimes do not seem to have been effective. The reasons for this are several. First, the precariousness of wages meant that there was much more to gain by being corrupt than by being honest; on the other hand, the harshness with which the mildest crimes of corruption were punished impelled, when corruption existed, to a greater magnitude of it, that is, to try earn as much as possible as soon as possible. An additional problem was the difficulty in determining what was corruption, especially when irregular taxes were a recognized necessity for managing the administration.

Finally, the risks faced by the plaintiffs meant that the crimes were only reported when the possible benefit derived from it outweighed the risks. The fact that the types of corruption that were punished most severely —that directed at the people— were the most common is a sign of the ineffectiveness of the punishment system.

The magnitude of corruption

As we have mentioned, an official usually tried to get the most out of his position in the shortest possible time. Popular thinking at the time seems to have been marked by the following assumptions: 1) that officials were almost always corrupt, 2) that those who were not corrupt could not prosper, and 3) that those who were honest abstained from participating in government.

The popular proverb "money falls into the hands of the administrator of the yámén like a sheep into the jaws of the tiger" (qián luòchā shǒu, yáng luò hǔkǒu 錢落差手, 羊落虎口) seems to account for this idea.

But how does this translate into numbers? Counting the annual legal income of all government officials we have an approximate figure of 6.3 million taels of silver, divided as follows: 1.4 million in salaries, 4.3 million in yǎnglián, and 0.6 million in administrative expenses (gōngfèi).

On the other hand, it is estimated that non-legal revenues in 1880 totaled 115 million taels, an amount more than 18 times greater. In turn, out of 23,000 civil servants, more than half of this income was concentrated in only 1,700 of them.

In rural areas, irregular land taxes were only possible when there was a surplus of agricultural production. Some studies (Shawn Ni et al., 2006) suggest that because officials had so much power in these areas, nominal ownership of land did not matter, as the official could collect the surplus by virtue of his position. In other words, the official's income would have been the same as if he were the owner of the land.

The Qīng government tried to stop corruption by increasing salaries by threefold. But by the time it did, corruption was already so entrenched that no possible fiscal increase could have uprooted it. As can be understood from the figures mentioned, the wage reforms had little impact because, despite being generous, they were still insignificant compared to the income from corruption.

The case of Héshēn

When we talk about corruption during the Qīng dynasty, we cannot pass by without mentioning Héshēn, a character who has gone down in history as one of the greatest villains of China. However, and as is often the case in the history of the country, much of what is said about Héshēn is more a legend than a reality. At the same time, the meritorious contributions he and his clique made to the dynasty are also forgotten.

As an exhaustive account of Héshēn's life escapes the scope of this article, we will try to synthesize.

Héshēn was a member of an aristocratic Manchu family who, at the age of twenty-two, began working as an imperial guard in the Forbidden City. It is believed that the emperor really liked him, as he ascended in a very short period of time – four years – to be part of the Grand Council (Jūnjī Chù 軍機處). This government body dealt with important matters such as supervising civilian examinations, supervising construction works, leading military forces in combat or managing the emperor's personal affairs. Since, at that time, the Great Council was not subject to the scrutiny of the Censorate (Dūchá Yuàn 都察院), it was a highly susceptible organism to corruption.

Although Héshēn strengthened his power over time, even marrying his daughter to one of the emperor's favourite sons, he was not the only member of the Great Council to do so. Qiánlóng also appointed Héshēn's political rivals as members of the Grand Council, so that two rival factions were established within the Grand Council: the Héshēn clique and a rival clique initially led by Ākèdūn 阿克敦 and Liú Tǒngxūn 劉統勳.

Wook Yoon, in his study of the relationships between these two rival factions, proposes that Emperor Qiánlóng used the dissensions and rivalry between the two as a tool to control corruption in the Great Council. Thus, the surveillance that both groups would have maintained over each other would have served as a limit to the corrupt activities of their members who, as we have said, were not subject to the supervision of the Censorate.

Héshēn 和珅.

Normally, the time of Héshēn's rise is seen as the time when the Qīng dynasty went from splendor to decadence. However, it is often forgotten that around this same time, some of the Qiánlóng government's most successful military campaigns were led by members of the Héshēn faction, who oversaw the projects to finance them. Likewise, the empire's finances were also remarkably prosperous in the decades they were managed by Héshēn.

The key moment, then, which seems to be linked to Héshēn's most corrupt activities, was the end of Qiánlóng's formal reign. The emperor abdicated in 1796, as a gesture of filial piety towards his grandfather Kāngxī 康熙, who had reigned for sixty years—a reign longer than any other emperor in China. Qianlóng, who had ascended the throne in 1735, did not want to reign more than his grandfather. At least, officially, because he continued to serve as de facto emperor until his death in 1799.

These years after Qiánlóng's abdication would coincide with the time when Héshēn's political rivals within the Grand Council, who were already in advanced age, were gradually withdrawn from their positions and replaced by young and inexperienced members. With them, the rival faction that served as supervision of Héshēn's group disappeared.

Likewise, the senility of Qiánlóng himself, who was progressively losing faculties, allowed Héshēn to control the policies of the court in the following years. These factors would leave the way open for Héshēn and his followers to unleash their corrupt activities.

Emperor Qiánlóng 乾隆.

One opportunity that Héshēn seized to enrich himself was the White Lotus Rebellion (Chuānchŭ Báiliánjiào Qǐyì 川楚白蓮教起義), which had broken out in 1796. During the first years of the war that followed, Héshēn controlled the expenditure of military funds. It would later be seen that more than half of these funds were diverted directly into the pockets of corrupt commanders.

Héshēn hid reports to the emperor of the defeats inflicted on government troops and militias, inventing false victories and non-existent armies. It was later discovered that a large part of the militiamen who were being recruited to deal with the rebellion were "ghost soldiers", and did not really exist. Their false names were listed so that the military officers who supposedly commanded them could pocket their salaries, as well as any equipment funds and supplies they would have needed had they existed.

But that was not all. When royal militia soldiers were killed in combat, their families had the right to receive death compensation. The corrupt officers found a way to pocket these financial compensations themselves, which in turn served as an incentive for them to send more soldiers to needless deaths.

The White Lotus War was a disaster for the dynasty, in which huge amounts of funds were invested that were never used in the war. However, corruption was not the only cause of this disaster. Other factors contributed significantly, such as the emergence of other uprisings in different regions, the conditions of the terrain and climate in which the fighting took place, or the absence of competent generals—as some of the most capable generals of Héshēn's faction had recently been killed in combat.

It is impossible to expand here further on the White Lotus Rebellion, a historical event that deserves at least a lengthy article in itself. Suffice it to emphasize, then, that corruption, although it was perhaps not the decisive factor, was at least a great burden for the suppression of this uprising that lasted eight years.

After Qiánlóng's death, his successor, Emperor Jiāqìng 嘉慶, soon ordered a full investigation into Héshēn's crimes. It is interesting to note that although the literature on Héshēn made him famous as the most corrupt man in Chinese history, the most important crimes for which he was prosecuted were political, and for the most part correspond to the years after Qiánlóng's abdication: falsification of edicts, concealment of reports, removal of names for important appointments, etc.

However, it was his wealth that has most marked his legend. Among his most notable possessions were his 730-room mansion and a 620-room second residence; productive farmland with an area of almost 500 square kilometers and a multitude of objects made of gold and silver, jade and precious stones. He also owned several banks and pawnshops.

Estimates of the total value of his posessions range from impossible figures like 800 million taels (equivalent to four times the entire gross domestic product of the United States; a totally overestimated figure), to Wook Yoon's proposal of four million taels, which is a large figure but not at all unexpected for someone of Héshēn's position. Surely reality is somewhere in the middle between the two extremes.

After his trial, Héshēn was forced to commit suicide. Emperor Jiāqìng, out of respect for his sister, who was married to Héshēn's son, allowed him to hang himself with a silk rope, instead of ordering his death by quartering, which was the rightful punishment for his crimes according to law.

Conclusions

As we have seen, low salaries and the need for irregular sources of funding for the administration, coupled with social pressures and the dependence of civil servants on clerks, made the administrative structure highly susceptible to corruption, to say the least.

The members of each ministry demanded payments not only from the people, but also from the members of the lower levels of the administration. So the lower down the administrative ladder an employee was, the more pressure he received that impelled him to corrupt practices.

While some practices were tacitly approved by the government due to sheer necessity, they were perceived as unfair by the rest of society, and the image of the government official was inevitably associated with corruption and oppression of the people.

Despite this, the general attitude of the Chinese people was one of resignation to a situation perceived as irremediable and, during the eighteenth century, it does not seem to have been subversive. This attitude would change towards a growing hostility to the government throughout the nineteenth century, leading to major uprisings and social unrest.

The root of corruption seems to have appeared as early as the Mingo dynasty. The founder of this dynasty, Zhū Yuánzhāng 朱元璋, who came from humble origins, strove to relieve the peasant population by reducing taxes and, consequently, the government budget and the salaries of civil servants. This reduction in salaries triggered further corruption already during Míng.

With corruption already entrenched for three centuries, the reform attempted by the Qīng emperors was now absolutely unfeasible and doomed to failure. The Manchu dynasty thus went into the popular imagination as the most corrupt in the history of China.

Sources:

Corruption in Eighteenth-Century China, Nancy E. Park. Journal of Asian Studies - J ASIAN STUD. 56. 10.2307/2658296 (1997).

Bureaucratic Corruption in Nineteenth-Century China: Its Causes, Control, and Impact, Chong-chor Lau and Rance P.L. Lee. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (1979), pp. 114-135.

High corruption income in Ming and Qīng China, Shawn Ni, Pham Hoang Van. Journal of Development Economics, Volume 81, Issue 2 (2006), Pages 316-336.

Prosperity with the Help of "Villains," 1776-1799: A Review of the Héshēn Clique and Its Era, Wook Yoon. T'oung Pao. 98. 479-527. 10.2307/41725992 (2012).

El Crepúsculo Imperial: La guerra del Opio y el fin de la última edad de oro china, Stephen R. Platt. Ático de los Libros, 2024