In all Chinese Martial Arts circles is rooted the belief that it was Bodhidharma, known to the Chinese as Dámó 達摩, who transmitted Chán 禪 Buddhism to the monks of Shàolín 少林, and taught them certain physical exercises that would later develop into Shàolín Kung Fu. However, and although Bodhidharma's existence seems to be documented, the legend of his relationship with Kung Fu is based on a long oral tradition without historical basis, and we have no reliable evidence of its veracity.

As we saw in our article Chinese Martial Arts before Shàolín, there was already a long martial tradition in China before the arrival of Bodhidharma to the monastery in the year 520. It is also known that the monks practiced jiǎo dǐ 角抵, a ludic form of combat, and that some monasteries possessed weapons to defend against the attacks of bandits. In addition, the Wǔtái 五台 monastery was already famous for its martial arts, and it is known that its monks fought against the jurchen invaders, a Tungús tribe from Manchuria known in China as nǚzhēn 女眞, who would end up founding the Jìn 晉 dynasty.

Historical records on Bodhidharma

As Acevedo, Gutiérrez and Cheung point out in their book Breve Historia del Kung-Fu, based on the studies of various historians both Chinese and western, the stories about Bodhidharma are contradictory. Although it is believed that he was a monk of Indian origin, some sources cite him as coming from Persia. In addition, the existing texts of authors contemporary to Bodhidharma, locate their activity, either in Sōng Shān 嵩山, where the Shàolín temple is located, but without referring to it, or in Yǒngníng 永宁寺 monastery, in Luòyáng 洛阳.

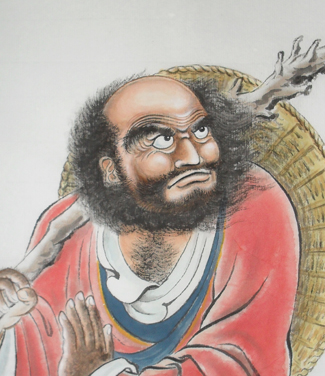

Chinese painting representing Bodhidharma

The first text relating Dámó to Shàolín is the Chuán Fǎ Bǎo Jì 傳法寶紀, Precious Record of Dharma Transmissions, written nearly two hundred years after his life. The earliest monuments dedicated to his figure in the temple also date from the 8th century, and it is from that same period onwards when other texts begin to appear associating him with the temple, an association that will be consolidated over the years.

However, the attribution of martial knowledge to Bodhidharma does not occur until more than a thousand years later, in the Yì Jīn Jīng 易筋經 or Tendon Change Classic, a treatise that collects the famous Qì Gōng 氣功 exercises known by the same name, and to which martial applications are attributed. Legend has it that Bodhidharma left the monks a series of texts including the Yì Jīn Jīng and the Eighteen Luohan Hands, among others. However, the first is the only one that has survived. In it, the author, a Taoist monk from the 17th century called Zōng Héng 宗衡, attributes the text to Bodhidharma, as a legendary character, with the intention of bringing credibility to his work, a practice that was very common among ancient Chinese writers. Following the reasoning of Acevedo et al., which cite professor Meir Shahar, the attribution of martial knowledge to Bodhidharma should be due to Zōng Héng's ignorance of the fact that the monks themselves already attributed the origin of their martial arts to Vajrapani or Jīngāngshǒu 金剛手, a protective deity of Buddhism. Subsequently, due to the great diffusion of the Tendon Change Classic, the monks would adopt the myth of Bodhidharma as the founder of Shàolín Kung Fu.

But legend has not only placed Dámó as a transmitter of the secrets of Kung Fu, but this same legend also seems to have exaggerated the martial abilities of the temple monks.

Recorded History of Shàolín Monastery

Although there are documents that speak of an early martial practice in Shàolín, according to historians, between the 7th and 13th centuries there are no written sources to account for their continuity. In the Yuán 元 dynasty (1271-1368) these references reappear, which speak of the monks' fighting ability with the staff. Some later authors refer already to the very staff techniques used by the monks. General Qī Jìguāng 戚继光 (1528-1588) names the Shàolín staff method in his New Treatise of Military Efficiency, Jìxiào Xīnshū 纪效新书; however, when he comes to exposing the techniques of combat with staff, he prefers those of general Yú Dàyóu 俞大猷. Yú himself visited the Shàolín monastery and, according to him, was disappointed by the monks' poor skills. After making a demonstration of his own abilities, the monks asked him to teach them but, considering that they needed several years of practice, he only accepted that two of them would accompany him to learn from him. These monks returned to the monastery to transmit the general's staff method after three years of learning.

Chéng Zōngyóu 程宗猷 is another author who, not only names, but exposes the staff techniques of Shàolín in a manual, after having learned himself in the temple, from which he says that only a few monks were skilled fighters. Another author, Wú Shū Zhuàn 吳殳撰, criticises the monks for using the spear as if it were a stick, without knowing the techniques of this weapon.

During the Míng 大明 dynasty, China's eastern coast suffered frequent attacks by both Chinese and Japanese pirates. The Chinese Government supported the creation of militias to deal with these attacks, some of which were made up of monks, both from Shàolín and other Buddhist monasteries. It is believed that it was at this time when the Shàolín monastery acquired its fame in martial arts, overshadowing other monasteries that also practiced them.

Shàolín Temple in Sōng Shān.

On the other hand, the temple's historical records do not account for the activities of the monks as fighters, a fact that could be explained as an intentional way to cover up the violation of Buddhist rules of not inflicting harm on others. The practice of martial arts in monasteries as something common seems to be explained, among other reasons, by the fact that many martial artists, like other scholars, rented dependencies in their precincts in order to have a quiet place to teach.

Another legend that seems to be exaggerated, despite having a historical basis, is that of the rescue of Emperor Tàizōng 太宗 of the Táng 唐 dynasty by thirteen monks who, armed with iron rods, fought against an entire army. This legend originated some thousand years later from the facts it intends to narrate, and most likely some monks participate in the fight along with the army of the emperor himself.

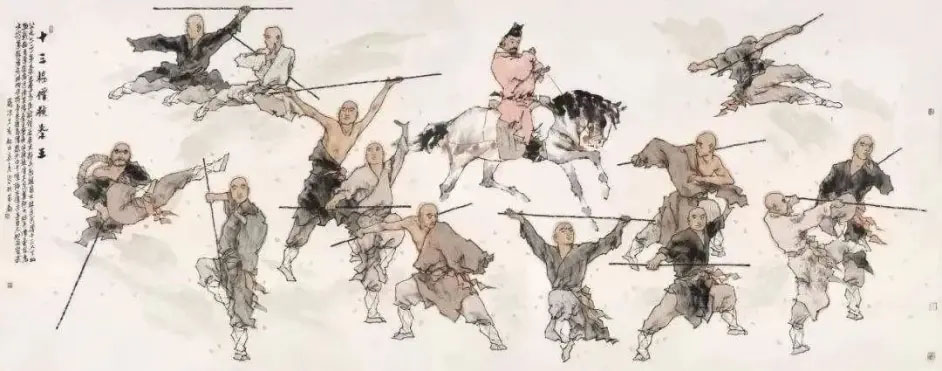

The legend of the thirteen monks who fought alongside Tàizōng

In the year 621, Tàizōng was in the vicinity of Mount Sōng facing the army of Wáng Shìchōng 王世充, a general who had served the Suí 隋 dynasty to later depose the last emperor of the dynasty and proclaim himself as Son of Heaven. In the beginning, luck seemed to favour Tàizōng, but after the arrival of reinforcements of the enemy, the scales tipped in favour of Wáng Shìchōng. When all seemed lost to Tàizōng, thirteen monks from Shàolín armed with long iron rods appeared on the scene to lead an attack on Wáng's army and capture his nephew. According to some versions of the legend, the thirteen monks defeated the entire enemy army by themselves; and according to another version they managed to rescue Tàizōng himself who had been made prisoner.

Although there are many records that account for the participation of the monks in the battle, the magnitude of the feat has certainly been exaggerated over the years. It seems that, in fact, Tàizōng's army was quite bigger than his opponent's. In addition, some historians (Shahar, 2000) believe that the participation of the monks in this episode was due to, on the one hand, the fact that Wáng had appropriated certain lands belonging to the monastery and, secondly, to the persecution of political advantages, after having considered carefully which side was more likely to emerge victorious.

Taking part in combat was not a decision of the temple order itself, but only of a group of isolated individuals; in fact, participation in political affairs was forbidden in the monastery. However, Emperor Tàizōng was very grateful to the monks for the help provided and, because of that, Shàolín was the only monastery that was saved from the persecution initiated by Tàizōng himself against the Buddhist religion.

There are also some shadows on the legend of the destruction of the temple, burned by imperial officers during the Qīng 清 dynasty, and of which only five monks survived: Lǐ Shìkāi 李式开, Hú Dédì 胡德帝, Mǎ Chāoxīng 马超兴, Fāng Dàhóng 方大洪 and Cài Dézhōng 蔡德忠. On the burning of the temple at this time no historical record has been found. The names of the surviving monks have not been found in the records of the temple itself. This story seems to originate in the secret societies which fought against the Qīng dynasty, of Manchu origin and, therefore, a foreign one. The names of the five monks appear in the documents of the Hóng Mén 洪門 party, one of these societies, as founders of the secret society Tiān Dì Huì 天地會, Society of Heaven and Earth. These documents also name legendary and literary characters among their members, with the intention of attracting followers towards their cause.

Finally, there is also no historical reference to the existence of a Shàolín temple in Fukien (Fújiàn) 福建 province, of which many styles of Kung Fu claim offspring; and it is possible that this legend also originated among the referred secret societies of the Qīng era. Recently, a Southern Shàolín temple has been built in Fújiàn province, to take advantage of the current boom of Kung Fu and the commercial success that the original temple, and everything related to Shàolín, have nowadays.

Concluding, we see that the history of Kung Fu in general, and that of Shàolín in particular, are riddled with myths whose historical foundation is, many times, minimal. It is clear that these stories bring a degree of romanticism certainly appealing, and our intention is not least to destroy the beauty they may have, but it is also true that they have suffered a high degree of manipulation. Behind this manipulation lurks an intention that has been, and still is, attracting adepts, either in the form of partisans of one or the other faction in the past, or of prospective clients in the present.

Therefore, we consider that Kung Fu must be valued for the beauty it has in itself, for its usefulness as a defense system and for the benefits that it brings us, both physically and mentally or spiritually, but never for the mythical origins attributed to it or for tracing its origin back to a certain legendary lineage.

Sources:

- William Acevedo, Carlos Gutiérrez, Mei Cheung, Breve Historia del Kung-Fu, Madrid, 2010.

- Meir Shahar, Epigraphy, Buddhist Historiography, and Fighting Monks: The Case of The Shaolin Monastery, Taiwan, 2000.