In the second half of the twentieth century, the so-called modern wǔ shù was officially established. This new wǔ shù was characterized by flashy and difficult-to-execute acrobatic movements, but devoid of any martial use, leading to a new era in which exhibition martial arts would gain ground to the traditional ones, to the point that the latter are virtually extinct to this day. However, these exhibition arts had been present in China for several hundred years.

Wǔ shù (traditional Chinese 武術, simplified 武术) is a term that literally means "martial arts". Although, today, this term is used to designate exhibition martial arts, we should refer to them as "modern wǔ shù" and to traditional martial arts as "traditional Kung Fu" or "traditional wǔ shù".

Historical antecedents

During the Sòng dynasty 宋朝 (960-1279) there were already exhibition styles in China, practiced by the civilian population at fairs and festivals. These styles were profuse in acrobatic movements whose objective was pure spectacularity, and barely included any effective techniques for combat. These movements, known as huā fǎ 花法 or "flowery techniques", often received criticism from the military, and resulted in the distinction between martial practice for real combat (實戰武藝 shí zhàn wǔ yì) and martial practice for display (花法武藝 huā fǎ wǔ yì).

At the end of the Sòng period, these exhibition arts were already the main spectacle at festivals and fairs, and their practice continued even during the Yuán dynasty 元朝, when real martial arts were forbidden.

In later centuries, during the Qīng dynasty 清朝, the "flowery techniques" of exhibition martial art were introduced into the practice of some military forces. The Green Banner Army (綠營兵 lùyíngbīng), a military group composed of Chinese of the hàn 漢族* ethnic group, suffered criticism from various army officers and even from emperor Jiāqìng 嘉庆, for the use of such techniques in their training. These voices claimed that the practice of this military group was pleasing to the eye but lacking martial utility, and therefore only useful for exhibitions.

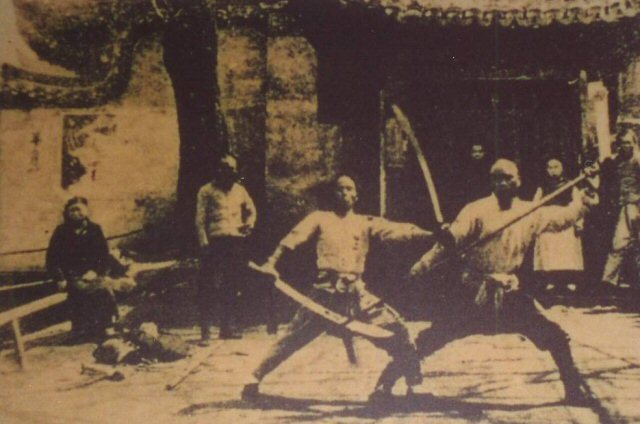

Martial arts exhibition at a market in Shànghǎi 上海, around 1930.

The establishing of modern wushu

The last development of these non-martial arts took place after the establishment in 1949 of the People's Republic of China under Máo Zédōng 毛澤東. Máo valued physical exercise as a method of strengthening, not only of the human body, but also of the entire nation. However, the communist leader considered that the existence of many training methods caused confusion and was therefore negative for "bones and muscles". This diversity of methods included the different styles of Chinese martial arts.

Under this same point of view, the Communist Party promoted in 1951 the organization and standardization of martial arts practice. In 1957, the National Sports Commission (guó jiā tǐ wěi 國家體委) established physical education and non-combative competition as the objectives of the modern wǔ shù.

With the Cultural Revolution (無產階級文化大革命 wúchǎn jiējí wénhuà dà gémìng, "Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution", 1966-1976), the elements of traditional culture, which were considered remains of a feudal past, were harshly persecuted and, in many cases, destroyed. Many intellectuals and martial artists were also the subject of this persecution. Only in isolated areas, where the Cultural Revolution did not arrive with such intensity, were some martial arts styles able to survive.

From this moment the practice of combat was eliminated and the traditional master-disciple relationship, also considered as a feudal element, was abolished. Self-defense techniques were no longer needed in the new established order and in the face of new warfare technology, and began to be regarded as useless. The traditional relationship was replaced by the new coach-athlete relationship.

The traditional teacher-disciple relationship was also an adoptive parent-adopted son relationship, as highlighted by the term "master" (shīfu 師父, composed of the characters shī 師, "teach" or "teacher", and fù 父, "father").

For more information on this aspect, see the article "The Role of the Master in Chinese Tradition".

Swordsman performing in the street. Shànghǎi, circa 1910.

Various expert meetings, convened by the Communist Party, unified different martial styles and established standardized routines, competition standards and scoring systems, all based on aesthetic rather than practical criteria. Thus, the new scoring rules gave greater value to flashy and difficult-to-execute movements than to those related to martial effectiveness.

Moreover, a new belt classification system, not existing in traditional Chinese martial arts, was introduced, imported from Japanese martial arts.

The modern wǔ shù has received numerous critiques from traditional martial artists, to the point of being regarded by some as sports gymnastics and even as "dance arts" (wǔ shù 舞術), an expression that is pronounced identically but written with different characters.

The new trend and the expansion of exhibition martial arts has jeopardized the existence of traditional martial arts, to the point of being very difficult to this day to find teachers who teach truly-martial arts, in the pure meaning of the term. In China, Kung Fu is regarded by today's generations as a useless practice, for the rare probability of being put into practice in today's life.

Note:

* The Qīng dynasty was of Manchu origin, so at that time the regular army was composed mostly of Manchus.