Introduction

Chan Heung 陳享 founded Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 in 1836, while also beginning the teaching of his martial art. In 1848, his pupils began to open other schools in the nearby regions. Undoubtedly, one of the most renowned was the Hung Sing Gun 鴻勝館 of Fóshān 佛山.

Cheong Jim 張炎 was one of the most relevant teachers in charge of this school. He is also the founder of a style of his own somewhat different from Chan Heung's, which was called Hung Sing Choy Li Fut 鴻勝蔡李佛 (with the Hung meaning "goose"; for more information on this name see our previous article Chan Heung's Legacy and the Style Branches).

In this article we will focus on the figure of Cheong Jim and the school he took over. For convenience, throughout this article, when we name the school or the Hung Sing style, we will be referring to the Hung Sing of Fóshān (as opposed to the Hung Sing 雄勝 of King Mui 京梅).

Chan Heung 陳享, founder of Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛.

Foundation of the Fóshān Hung Sing School

The first of Chan Heung's students to open a school was Lung Zi-Choi 龍子才 in Guǎngxī 廣西 Province. Immediately thereafter, Chan Din-Jau 陳典尤 and Chan Din-Wun 陳典桓 (in other sources transliterated as Chan Din-Fune) were sent to the nearby city of Fóshān to transmit Chan Heung's teachings there.

There, they opened a school linked to Chan Heung's organization, called, like the rest, Hung Sing 洪聖 ("Great Sage"). However, a short time later, with the Red Turban Rebellion of 1854-1856 (Guǎngdōng hóng bīng qǐyì 廣東洪兵起義), the school had to close its doors, as the entire province was plunged into chaos and violence. This rebellion was led by members of the Tiāndìhuì 天地會 secret society and joined forces with the Tàipíng 太平天國 rebels.

In 1854, the Red Turban troops took the city of Fóshān and attempted to take Guǎngzhōu 廣州, which was defended by irregular militias in the service of the government, supported by the British army, causing the attempt to fail.

It is unclear what role the Choy Li Fut school of Fóshān played in these events. Today, some practitioners of the style claim that the school was involved in rebel movements.

This is a statement that is repeated over and over again in the mythology of Choy Li Fut but, again, there is no proof of its veracity. After the suppression of the Red Turban Revolt, the repression of suspects throughout Guǎngdōng 廣東 province, according to some estimates, reached the figure of one million executions. Among them, entire groups, such as the troupes of opera actors, among which there were many martial artists, were put to the sword.

At the time, other schools in Chan Heung's organization were operating openly, so they do not appear to have been the subject of suspicion by the government. On the other hand, and although the Fóshān school was closed when the city fell into rebel hands, its subsequent success suggests that it was not viewed with suspicion by the government either.

However, it is possible that practitioners of the style were among the rebels in their personal capacity, just as it is quite possible that there were also among the government militias.

After the suppression of the revolt, the Fóshān school was not immediately reopened. Although the reason is not known for sure, it is possible that it was necessary to wait for the waters to calm down before resuming activity. It wasn't until 1867 that Chan Heung sent another student to reopen the school.

Cheong Jim, fact, legend or fiction?

We know very little about Cheong Jim's life. It is believed that he was born around 1814, but the date of his death is disputed, and varies between 1844 and 1893.

While, at one extreme, some say he never existed, others argue that he was a member of secret societies and therefore there are no written records about him—although secret societies left behind historical records, membership certificates, and membership lists.

Most of the facts about Cheong Jim that have passed into legend are the product of later fiction novels. We are going to narrate his story as this legend imagines it.

The legend of Cheong Jim

Cheong Jim had been born in a village in San Woi 新會 district and had been orphaned at a young age, so his uncle had taken care of him. At a young age, he began his martial arts training with Li Yau-San 李友山, the same person who had been Chan Heung's second teacher.

In 1836, his uncle had to move to another location and, unable to take his nephew with him, asked his friend Chan Heung, who had just returned to his native village of King Mui, to take care of the young man. Chan Heung took him into the village, and Cheong Jim began working there as a gardener.

In those days, it was not allowed to learn a style of Kung Fu to those who were not clan members and bore the family name, so Cheong Jim could not attend classes where the new Choy Li Fut style was taught. However, Cheong Jim was not a novice in martial arts and was able to copy the moves he saw the Chan clan members perform. Thus, he secretly trained at night when no one was watching.

But one night, Chan Heung himself, who had gone for a walk, discovered Cheong Jim practicing the same moves he taught. Chan Heung was surprised by the young man's great ability, and decided to teach him secretly, behind the clan elders' backs.

Several years passed in which this training was kept secret; Chan Heung would meet his young student at night to teach him without anyone else knowing. But one day, while Chan Heung was outside the village, the students of the village belonging to the family clan rebuked Cheong Jim and the dispute ended in a fight. It seems that Cheong Jim emerged victorious from the encounter, but upon seeing him use the moves that Chan Heung had taught him, it was revealed that he had been receiving training. The clan elders forced Chan Heung to expel Cheong Jim from the village.

Chan Heung had to comply with the order, but he sent his disciple to continue his training with a monk whose Buddhist name was Ching Chou 青草, 'Green Grass', who lived somewhere in Guǎngxī Province. Cheong Jim is said to have found the monk and for eight years, from 1841 to 1849, learned from him the Fat Ga Kyun 佛家拳 style of the Buddha Palm.

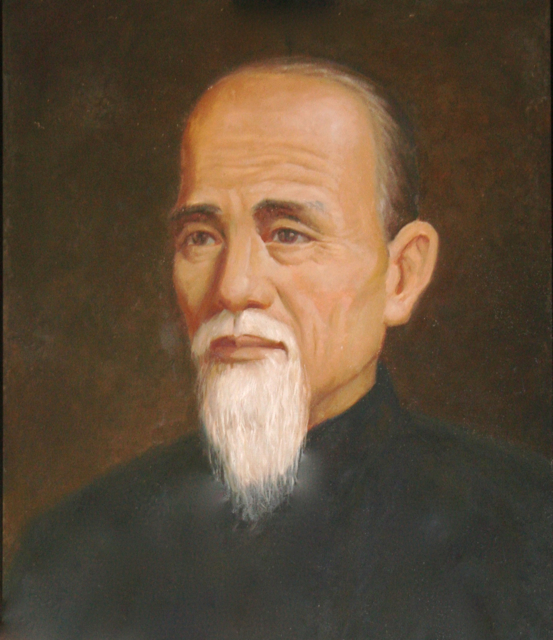

Image of Cheong Jim 張炎 preserved in the Hung Sing Gun 鴻勝館 in Fóshān 佛山.

Different versions of the legend:

After learning from Ching Chou, Cheong Jim returned to Fóshān where he trained fighters to nurture the Tàipíng rebellion. Practitioners of the Hung Sing style of Fóshān believe that it was Cheong Jim himself who founded the school, and not Chan Din-Wun and Chan Din-Jau. They also state that, in those years, Chan Heung and Cheong Jim met again, and that Cheong Jim shared with his former master the techniques he had learned from the monk Ching Chou —some also identify the monk Ching Chou with Choy Fook 蔡褔 himself—. According to this version, it would be in 1850 when Chan Heung and Cheong Jim, together, systematized the Choy Li Fut style, and that is why the Fóshān branch considers both of them as co-founders.

As we can see, Cheong Jim's story has more elements of legend than reality. The Chan family tells us that Cheong Jim was a disciple of Chan Heung in the years when he would have taught in Hong Kong 香港.

What is clear is that he was a disciple of Chan and that he reopened the school under Chan's authority in 1867. However, unlike the Chan Gun-Bak 陳官伯 schools, which changed the Hung (洪) character of their names to the Hung meaning "hero" (雄), Cheong Jim changed it to the homophone character meaning "goose" (鴻).

It also seems to be responsible for the distinctiveness of Fóshān's Choy Li Fut style, which is why this style is known as Hung Sing Choy Li Fut and he is known as Cheong Hung Sing 張鴻勝.

Master Wong Zan Gong 黄振江 of the Hung Sing Gun 鴻勝館 of Fóshān 佛山

practicing a staff form.

The legendary narrative about Cheong Jim originated in a fictional novel published in the 1930s by Xǔ Kǎirú 許凱如, a writer who wrote under the pseudonym Niànfó Shānrén 念佛山人 (or niàn Fóshān rén, "one who longs for Fóshān"). This novel, titled "Fatsan Hung Sing Gun" 佛山鴻勝館 reimagines Cheong Jim's life and gives him the role of co-founder of the Choy Li Fut style.

The novels of "martial fiction of the Guǎngdōng school"

Novels in the genre known as "Canton School martial arts fiction" (Guǎng pài wǔ xiá xiǎo shuō 廣派武俠小說) enjoyed an explosion of popularity since the 1930s. In addition to being distributed in book form, they were also distributed in serialized form in newspapers and publications in Hong Kong and Guǎngdōng.

Many of these fictional stories had such an impact that they greatly influenced the popular imagination and came to replace the real stories of the characters who starred in them.

These novels were a way to build a local identity based on values such as heroism and opposition to authority. While they succeeded in this endeavour, they also managed to obscure the real origins of many local martial styles, embedding the romanticized fictional stories into the local traditions that have been passed down to the present day.

Thus, stories of the imagined origins of South Chinese martial arts styles must be treated with caution, and understood as representing the ideals of the time in which they were propagated—after the emergence of these styles—rather than as true historical facts.

Xǔ Kǎirú was inspired by another very influential author of the same genre, Dèng Yǔgōng 鄧羽公, whose works told stories of the Shàolín 少林 temple and turned another martial artist from the region, Wong Feihung 黃飛鴻, into the well-known local hero he is today.

As far as Cheong Jim and the Fóshān school are concerned, Xǔ Kǎirú is responsible for introducing revolutionary activities into the popular imagination and implanting them in people's memory.

However, many present-day practitioners of the Hung Sing branch are stubborn in the idea that the Hung Sing association trained revolutionary fighters and that the Qīng 清 government would repeatedly send troops to try to shut it down—which, had it wanted to, it might well have done. All these ideas are the product of the mythology created well into the twentieth century, already in the republican era after the fall of the dynasty, as a way of boosting the reputation of the school to attract followers, and when these revolutionary ideas about the past were accepted and did not cause any repression by the new government.

In any case, we do not understand what merit could be brought to today's practitioners by the fact that their school had participated in revolutionary activities in the past such as the Tàipíng rebellion, led by an alienated man who believed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ and was dedicated to the burning of Buddhist and Taoist temples and the genocide of Manchus. and whose actions triggered one of the worst wars of humanity, which would end up claiming the lives of twenty million Chinese.

The Hung Sing school was, in fact, involved in politics and the anti-Qīng movement, but in much later era, as we will see in the next article.

Conclusions

The true information available about Cheong Jim is extremely scarce. The narrative about his life is, therefore, a legendary construction, we do not know if it is a cause or a consequence of the absence of real data.

One of the most important assertions of this legend is the attribution to Cheong Jim of the founding of Choy Li Fut together with Chan Heung. There is enough evidence of the founding of Choy Li Fut unilaterally by Chan Heung to lend credence to such a claim; moreover, the styles of Chan Heung and Fóshān's Hung Sing Choy Li Fut are quite different.

It is, however, fair to consider Cheong Jim the founder of a different style of Choy Li Fut, as is the case with Fóshān's Hung Sing.

The Hung Sing School enjoyed great success until the first half of the 20th century, despite the setbacks suffered by the chaos and altercations of the time. However, its success is due more to having been an open and public school, and not to having trained rebel fighters in secret.

After Cheong Jim's death, Chan Ngau Sing 陳吽盛 took over the Hung Sing school and, under his leadership, the school achieved remarkable success, becoming one of the most membered martial arts associations of its time. In the next article we will investigate these issues.

Sources:

Hamm, John Christopher. Paper Swordsmen: Jin Yong And The Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel, 2005 University of Hawai’i Press.

Dian H. Murray, Qin Baoqi. The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History, 1994 Stanford University Press.

Benjamin N. Judkins, Jon Nielson. The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. University of New York Press, 2015