Introduction

We have previously discussed how martial arts are influenced, at the time of their creation or development, by the socio-historical context in which they emerge. For this reason, they must reflect, at least in part, the reality of violence in the society and historical period in which they were created.

Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 Kungfu is a southern martial arts style that arose during the Qīng 清 dynasty (1644–1912), known for its powerful and devastating techniques, many of which target vulnerable points of the body—such as the throat, eyes, carotid sinus, joints, etc.—and are therefore potentially lethal.

In seeking to better understand our style, we decided to explore the concepts of self-defense as they were understood under Qīng dynasty law, expecting to find justification for the use of such lethal techniques in a self-defense context. However, to our surprise, upon examining the provisions of the Qīng legal code on this matter, we found that the law punished violence and homicide very harshly, even in cases of self-defense.

This article was born from an attempt to resolve this apparent contradiction and to answer the question of why a style like Choy Li Fut—as well as others that emerged in the same era and region, such as Hung Ga Kyun 洪家拳, Bak Mei 白眉, and, perhaps to a lesser extent*, Wing Chun 詠春—systematized such a wide range of dangerous techniques within a legal framework that allowed little room for self-defense.

Self-Defense in Qīng Law

The concept of self-defense involves a person’s right to take actions to protect themselves or another person in a situation of danger—actions that, under other circumstances, could themselves constitute a crime.

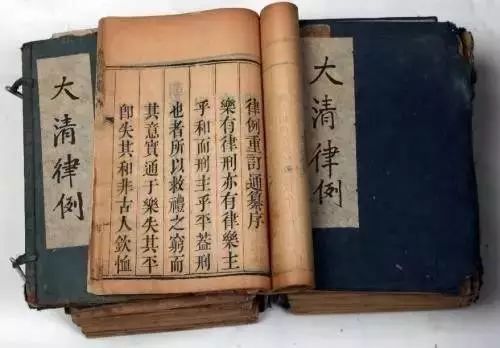

The main legislative body during the Qīng dynasty was the Dà Qīng Lǜ Lì 大清律例, which was derived from earlier legal codes of preceding dynasties. This code was composed of 436 statutes or articles (lǜ 律), which established permanent regulations, and more than a thousand sub-statutes (lì 例), which defined exceptions and specific cases, and were subject to periodic revisions. In this way, the system of sub-statutes allowed for adaptation to the different situations of a changing society, completing and clarifying the statutes—which had been enacted under different circumstances—and even being able to completely modify them. In cases where both a statute and a sub-statute were applicable, the sub-statute carried greater legal weight.

It is noteworthy that no mention of self-defense is made in the statutes of the legal code; it is in the sub-statutes where we can find specific considerations related to this concept.

In cases of homicide, the Qīng legal code was very clear: the guilty party had to pay with their own life. As stipulated in Article 290.1 (Chapter IX), anyone who, during a brawl, struck and killed another—whether with a hand, foot, object, or any other weapon—would be sentenced to death by strangulation. This article did not take into account the reasons behind the act, only its outcome. However, the sub-statutes associated with the article provided for a reduction of the sentence if the killer acted in defense of a third person (especially in the case of defending a parent or elder who was being attacked), commuting the death sentence to heavy bamboo beatings—a punishment that could still result in death—exile, or penal servitude, along with financial compensation for the victim’s burial.

The death penalty by strangulation extended even to cases of involuntary homicide, although there were also sub-statutes that mitigated the penalty depending on the circumstances. In the case of a brawl resulting in injury without death, the law did consider who had started the fight and who had a reason to strike—in self-defense; in such cases, the sentence could be reduced.

Even though self-defense was taken into account in the sub-statutes, there was no recognized right to self-defense as such, and its application depended on various factors, such as the presence of witnesses or the honesty of the magistrates handling the case. There was no guarantee of escaping punishment.

Although it is possible that in some more or less remote rural areas the law was not strictly enforced, and local clans and families took justice into their own hands, in general, the legal framework does not account for the nature of the Choy Li Fut style techniques, which are potentially lethal and target vulnerable points. To understand this, we must look beyond the legal framework and self-defense in urban societies, and delve into the sociopolitical context of the time, especially in rural areas.

Times of chaos and disorder

The 19th century was a period of growing instability; the increase in population had reduced the ratio of arable land, leading to a rise in banditry and struggles for local resources among different clans, widespread corruption, and insecurity that triggered rebellions and conflicts, further worsening the situation in the villages. In the suppression of these rebellions, peasants often suffered looting, both by the rebel groups and by government troops, under the suspicion that the villagers were harbouring rebels.

To this was added the activity of secret societies which, despite maintaining a rhetoric of fighting against oppression, were often groups defending their own interests and practicing predatory violence, engaging in clan wars over land and water resources. These groups operated outside the law and were persecuted by the government.

This situation frequently endangered both the properties and possessions of villagers—especially the crops on which their survival depended—and their very lives. Thus, when villagers were caught in violent situations, it is highly likely that their main concern was not the applicable legislation, but mere survival. It is within this context that we can begin to understand the nature of Choy Li Fut techniques, as well as those of other styles from the same period.

Villagers with rudimentary weapons and rattan shields.

On the other hand, it is important to note that the application of these techniques is only potentially lethal. In other words, the result of their use is not necessarily to end the opponent's life; rather, they can be used—despite the risks they carry—to neutralize or incapacitate the opponent quickly without causing fatal injuries: joint dislocations, loss of consciousness, broken bones, and, when weapons are involved, mutilation. In this case, as we saw earlier, the magistrate handling the case could indeed consider who struck first. However, investigations to clarify such cases often involved torture to extract confessions, making them undesirable for anyone, despite the possibility of being declared innocent.

Another factor to consider in judicial processes was the relative social status of the individuals involved. Due to the low salaries of government officials, who served as magistrates, they were highly susceptible to bribery (see "Corruption in the Qīng Dynasty"). In investigations and legal proceedings arising from scuffles and violent altercations, it was likely that the magistrate would be biased toward the party who could pay the most. Therefore, even acting in self-defense, it was dangerous for someone of low social status to use dangerous martial techniques for reasons other than defending their own life.

Finally, due to the insecurity described above, the local bourgeoisie of the villages would raise and train civil militias for the defense of the villages. These militias operated under the protection of the government and supplemented the work of the regular army, which often could not cover the defense of the country’s vast territory (though if the government suspected the loyalty of a militia, it could disband it). It is likely that when these militias were acting in defense of the village, the law would be more lenient in considering the injuries or deaths resulting from their actions, or that the legal system would have interpreted the use of force in such situations differently than in a civilian context, even though the militiamen were not part of the regular army.

For all these reasons, it is in the collective context of rural militias, who acted in defense of the villages against looting and rebellions, where the emergence and development of styles like Choy Li Fut is best understood, rather than in the context of individual self-defense.

Other factors that influenced the development of Choy Li Fut Kungfu

In addition to the reality of the violence of the time and the laws concerning self-defense, there were other factors that undoubtedly influenced the creation and development of southern styles such as Choy Li Fut, especially the restrictions imposed by the government on the practice of martial arts.

Contrary to what is commonly believed, the practice of martial arts among civilians was not prohibited during the Qīng government, but it was carefully monitored to prevent uprisings. The government was particularly suspicious of religious or superstitious groups, as these could use martial arts to spread anti-government ideas, as was the case with the Boxers (Yìhétuán 義和團)—this was the reason why secret societies were banned.

Member of the Boxers (Yìhétuán 義和團).

However, despite martial arts practice being permitted, there was a prohibition on the possession of weapons among the civilian population. This prohibition had a significant influence on the development of Kungfu styles in southern China, which is why most of them were developed around a core of empty-hand combat (unlike other eras when empty-hand techniques were rarely trained, as they were considered useless).

This restriction also influenced the popularity of the staff or long pole, as it was not considered a weapon, but rather a common accessory often used for walking. Therefore, many styles combined staff techniques with spear techniques, using the former to simulate and train spear movements.

Additionally, in the repertoire of Choy Li Fut, farmer tools such as hoes and rakes are included. These could be used to disguise the training of other forbidden weapons—such as halberds or the "horse-chopper" (zhǎnmǎdāo 斬馬刀)—and also provided very useful knowledge to peasants, teaching them to defend themselves with the tools they used daily for work.

The weapon prohibition also explains the use of other everyday objects in combat, such as the bench, the fan, or the transport pole, as well as, in the case of other styles, the meteor hammer (liúxīngchuí 流星錘), and "concealed" weapons, which could be easily hidden, like the butterfly knives (húdiédāo 蝴蝶刀), which were concealed in the wide sleeves of the period's attire, double daggers, or the nine-section chain.

Some butterfly knives (húdiédāo 蝴蝶刀) could be carried concealed in the sleeves.

Finally, we can assume that part of the training was carried out with wooden weapons or blunt-edged weapons, and therefore, were not subject to any restrictions.

In the case of civil militias, the prohibition on weapon ownership was somewhat looser than in private life. Militias were considered auxiliary bodies of the state, and they were allowed to possess certain weapons, as long as these were properly registered.

Conclusion

The right to self-defense, when considered in the individual context, does not account for the nature of styles such as Choy Li Fut, Bak Mei, or Hung Kyun. It is in the collective context of rural defense where this nature is understood. Villagers, often outside the protection of the regular army against aggression and looting by bandits, rebel troops, and secret societies, formed civil militias, under the umbrella of the government, to defend villages and crops.

Given the restriction on weapon ownership, martial arts schools of the time favored empty-hand combat or the use of weapons that could be mistaken for everyday objects (such as poles, fans, stools, agricultural tools like rakes, hoes, or machetes, etc.). It is also possible that some health exercises similar to Qìgōng 氣功 were used to disguise martial practice. Furthermore, it is likely that mou dak (wǔ dé 武德), or martial ethics, played a key role in teaching the controlled use of violence.

The powerful techniques of southern styles from the time often target vulnerable points on the body, such as the throat, eyes, carotid artery, and joints. In the case of techniques involving bladed weapons, many techniques aim to sever tendons and ligaments essential for movement. Targeting these points means being able to end a confrontation efficiently to eliminate the threat, while simultaneously having the tools to deliver definitive strikes if one’s own life is at risk.

Finally, since masters like Chan Heung 陳享—the founder of Choy Li Fut—trained civil militias, it is possible that the very lethality of their styles was a factor that, rather than limiting, favored their development and proliferation within the context of social insecurity.

Note:

*We do not mean to suggest that the techniques of Wing Chun are not equally lethal. However, it is noteworthy that while the other styles mentioned include a substantial repertoire of traditional weapons (swords, spears, knives, daggers, staffs, bench, and a long etc.), Wing Chun is characterized as an empty-hand system, to which the methods of long pole and butterfly knives were only added in recent times.

Sources: