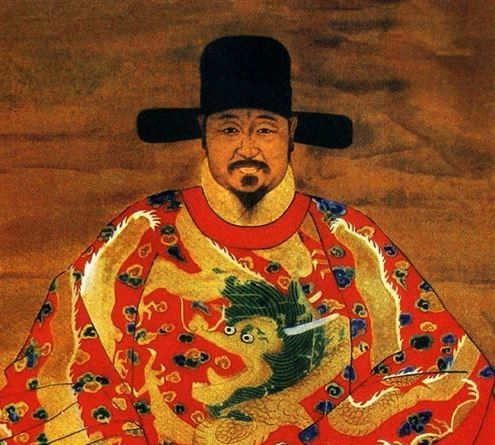

Qī Jìguāng 戚繼光 was a general of the Míng 明 dynasty, famous for leading expeditions against the attacks of the Japanese pirates wōkòu 倭寇 and later against the Mongols in the north. He was a military genius who, among other achievements, invented the "Mandarin Duck" formation (鴛鴦陣 yuānyāng zhèn), which we will examine in this article.

The wōkòu were pirates that, during the Míng dynasty, attacked China's coastal towns. Although the term wōkòu is usually translated as "Japanese pirates", the truth is that its ranks were made up of Japanese as well as Chinese and Koreans.

In the 16th century, the situation on the coast was out of control due to attacks by the wōkòu.

In 1555, Qī Jìguāng, who was in command of the coastal defense in the province of Shāndōng 山東, where he could not do much to fight the pirates due to the shortage of troops, was sent to Zhèjiāng 浙江, where the situation was especially delicate. He and two other Míng generals got a first victory in Céngǎng 岑港.

However, many of the wōkòu were former samurai and very well trained in the art of the sword, while Chinese troops defending the coast were made up of civilian militias with little training or experience. Similarly, the two-handed katanas or sabres used by the Japanese were a problem for Chinese troops, whose sabres were shorter.

To deal with this threat, General Qī Jìguāng designed a special unit, which he called "Mandarin duck" (鴛鴦陣 yuānyāng zhèn), composed of twelve men, of whom ten were armed, one carried the flag and the other performed only support functions, as a cook or carrier.

The mandarin duck formation

Unlike other duck species, mandarin ducks join a single couple for life and, therefore, in Chinese folk art and imagery they are always represented in pairs.

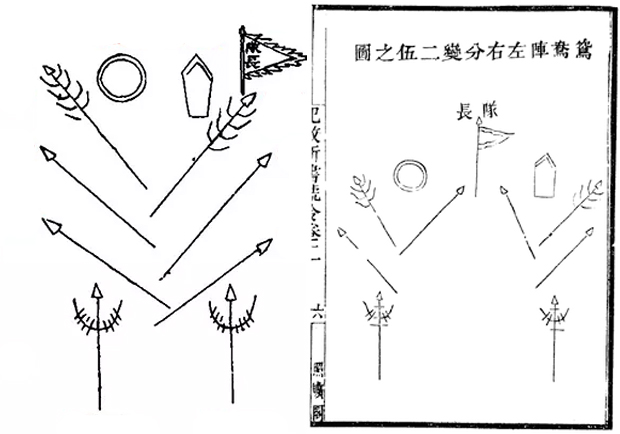

The "mandarin duck" formation received this name because it was composed of pairs of armed men, and could be divided at any time into two almost identical units of five men each.

The formation of ten armed men was composed as follows: two men with sabres and shields, two carrying lángxiǎn 狼筅 ("wolf brush"; see below), four spearmen, and two men armed with tridents. The unit worked in a coordinated manner so that each pair of men supported others. Let's look at it in more detail.

In the centre and in front were the two soldiers who carried sabres (dāo 刀) with shields. The one on the left, carried a rattan shield (téng pái 藤牌) and also a javelin (biāo qiāng 鏢鎗); and the one on the right, a long wooden shield called ái pái 挨牌.

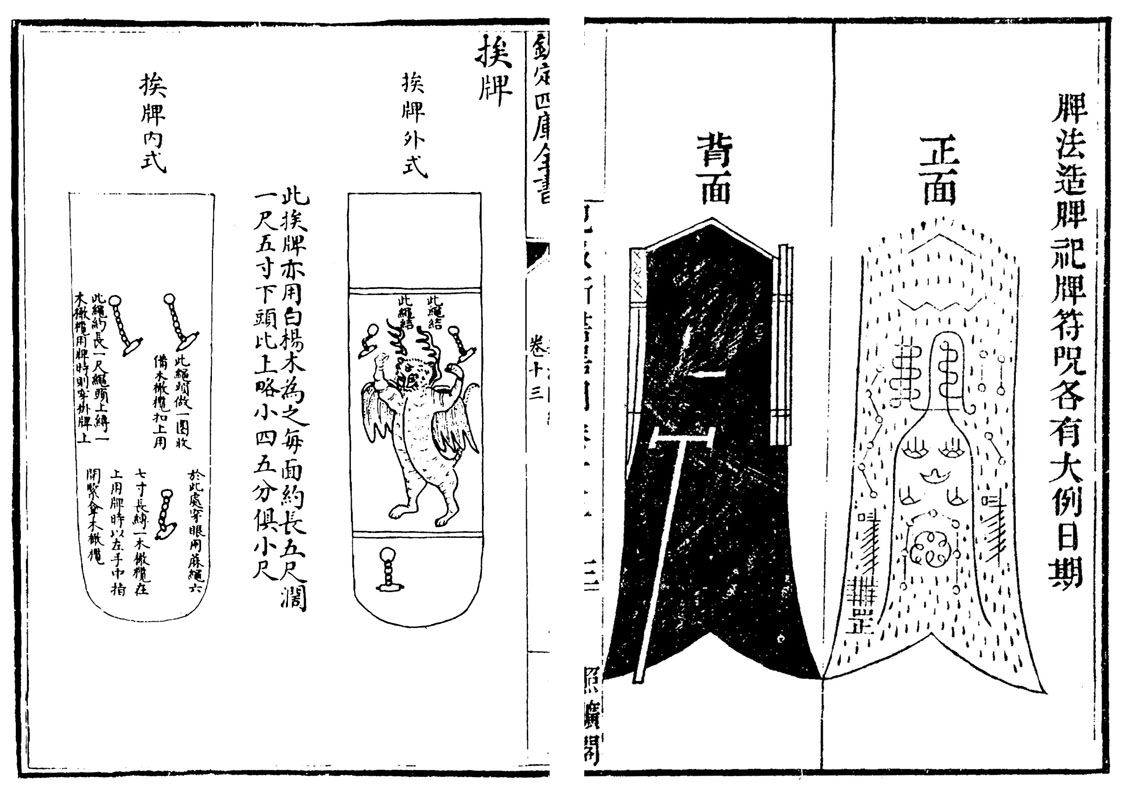

The ái pái 挨牌 (also written 捱牌)

The ái pái is a somewhat peculiar shield, since it does not have a handle to grab it, but a series of strings that work as follows. On the one hand, a rope allows the shield to be hung from the wearer's neck, while another string allows the left hand to direct or modify the position of the shield. In this way, the shield can be used with one-handed weapons, when directed with the left hand, or with two-handed weapons, leaving it the shield only hanging from the neck.

On the other hand, it has a wooden support that can be deployed as a easel, leaving the shield vertical on the ground, allowing the bearer to crouch behind it to protect himself from a rain of arrows.

Drawing of two different models of ái pái 挨牌.

Upon entering combat, these men protected those behind them with the shields. The one with the rattan shield could throw his javelin just before lashing out at the enemy. Enemy sabres could sometimes get stuck on the rattan shield, providing an opportunity for their carrier to take down their opponent with his sabre. The one with the wooden shield maintained his defensive position alongside the rest of the group. As these men carried short light onde-handed sabres, they needed the assistance of the rest of the unit, which carried long weapons.

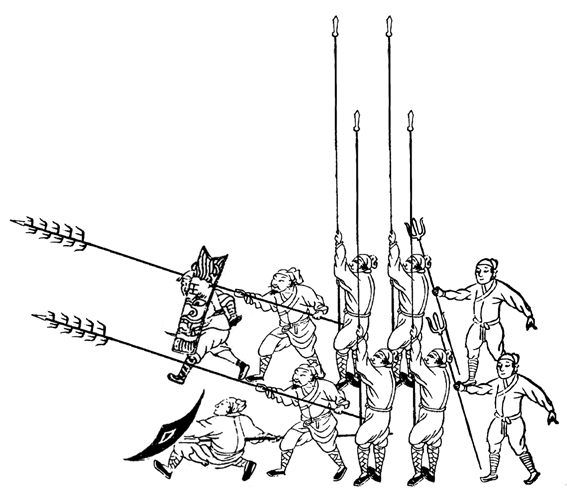

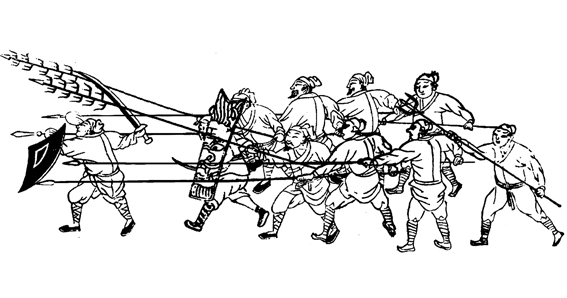

On both sides of these men were those who carried two lángxiǎn. The lángxiǎn is, simply, a long bamboo stick with branches, to which was added a spearhead at the tip, which was used to charge against Japanese swords with the intention of catching them between the branches. These men accompanied the swordsmen behind them, carrying the lángxiǎn forward above their heads, so that, despite walking behind them and therefore protected by the shields of the former, their weapons were ahead of them. By thus lashing out in a coordinated manner against the enemy, the lángxiǎn hindered their enemies by locking Japanese swords so that Chinese sabres, shorter than katanas, could approach and take them down.

Soldier carrying a lángxiǎn.

In turn, the four spearmen on the back, two on each side, carrying long spears, attacked at the same time from their sheltered position, when japanese swordsmen saw their sabres hooked in the lángxiǎn.

Finally, two men with tridents, shorter than spears, protected the spearnmen in case any enemy managed to get close enough to attack them.

The formation could be divided into two almost identical units.

The reason why the mandarin duck formation was genius is because through intelligence it managed to turn around the technical superiority of the enemies. We have already said that Japanese pirates were very well trained and very skilled at handling the two-handed sabre, which was longer than Chinese sabres. Chinese troops, with very poor training, were no match for them in singular combat. However, the mandarin duck formation, by using strategy, managed to invalidate the technical superiority of its enemies and give victory to these units with very little training and martial skills. In it, short and long weapons complemented and supplemented each other.

The "mandarin duck" formation in standby.

The "mandarin duck" formation in combat.

Despite being designed for small-scale clashes, this formation could also be used in large battles. Qī Jìguāng collected his methods in his New Treaty on Military Efficiency (紀效新書 jìxiào xīnshū).

When, in the 1590s, Korea suffered the Japanese invasion led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉, its troops were not prepared to make war on a large scale, and required the assistance of the Míng dynasty, which used General Qī's "mandarin duck" formation. Later, when the martial arts manual called Muye Dobo Tongji 武藝圖譜通志 was compiled in Korea, the shield and lángxiǎn techniques of General Qī Jìguāng were included.

Qī Jìguāng trained miners and farmers to deal with the raids of the wōkòu, and obtained great victories that contributed very importantly to the eradication of this threat.

The new mandarin duck formation

Years after fighting the wōkòu, General Qī Jìguāng was sent to the northern border to deal with the attacks of the Mongol tribes. He then modified his original formation to suit the conditions of war in the north, where enemies were nomads on horseback with great mobility. This "new mandarin duck formation" included firearms and an archer, who was the leader of the unit.