Introduction

Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 popular folklore associates it with the Tàipíng Rebellion 太平天國, secret societies, and other revolutionary movements that fought to overthrow the Qīng 清 dynasty. But, as we saw in the previous article on the life of Chan Heung 陳享, there is no evidence to support these claims.

We believe that it is worth dedicating a brief article to this topic, as it is a deep-rooted belief and should be studied with more caution.

The Tàipíng Rebellion

Southern China was the worst-hit region during the Opium War. Consumption was widespread and there was great discontent; the new infrastructure had put many porters out of work, and there was animosity among the local population towards the Hakka 客家人, an ethnic group from northern China that had recently established themselves in the region.

It was precisely a Hakka named Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全 who organized the revolt. An unsuccessful aspiring civil servant and convert to Christianity, Hóng had visions in which he discovered that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. The hatred and resentment that existed towards the Qīng received divine mandate: God ordered the extermination of the Manchus. Hóng proclaimed the Celestial Kingdom of Great Peace, Tài Píng Tiān Guó 太平天國, and headed north at the head of some 20,000 armed followers until he took the city of Nánjīng 南京, where a great carnage took place in which the Manchu population was exterminated.

Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全, leader of the rebellion.

In the north, General Zēng Guófān 曾國藩 organized an army of 120,000 peasant soldiers and, in a war that lasted ten years, recaptured Nánjīng and ended the rebellion. The official version says that the rebels were so fanatical that they all committed suicide, although it is more likely that a systematic massacre took place.

During the years of the rebellion, other uprisings took place in the rest of China, and it took another four years for the imperial army to put them down. It is believed that the imperial army was successful because the upper classes supported the dynasty.

The Legend of Chan Heung's Eight Original Forms

In some lineages, there is a legend that says that, at the time of the Tàipíng rebellion, and after founding the new style, Chan Heung created eight main forms. Joining the first word of the names of each of them was Tai Ping Tin Gwok Choeng On Man Nin 太平天國长安万年 (in Mandarin, Tài Píng Tiān Guó Cháng Ān Wàn Nián), "Long live the Celestial Kingdom of Great Peace", a revolutionary slogan.

After the rebellion was crushed by imperial forces, the Qīng government began hunting down anyone suspected of having participated in it. To avoid problems, the names of those eight main forms would have been changed.

The original forms are believed to have been:

Tai Zou Kuen 太祖拳, Form of the Supreme Ancestor, whose name alludes to the first emperor of the Míng 明 dynasty. This form was renamed until the one it currently retains: Mou Gik Kuen 无极拳. Currently very few schools know this way.

Ping Mun Kuen 平满拳, whose name literally means "Pacify the Manchus". The name of this form was shortened to Ping Kuen 平拳. Since the character Ping 平 also means "flat", "level", this form is usually translated as "Level Fist".

Tin Dei Sap Fong Kuen 天地十方拳, "The Ten Directions of Heaven and Earth". This name was shortened to Tin Dei Kuen 天地拳, Form of Heaven and Earth. "Heaven and Earth" was the name of a revolutionary anti-Qīng society. Later the name was changed to Sap Zi Kuen 十字拳, Cross Pattern Form (since the Chinese character 'ten' 十 is shaped like a cross). When the Siu Sap Zi Kuen 小十字拳 form was added to the system, the name of this form was changed again to Dai Sap Zi Kuen 大十字拳.

Gwok Fa Kuen 国花拳, Form of the National Flower. The peony had been the national flower for a long time, but the rebellion adopted the plum blossom as a revolutionary symbol, so this shape was also known as Mui Fa Kuen 梅花拳 or Plum Blossom Form. Again, when the form Siu Mui Fa Kuen 小梅花拳 was introduced into the system, the name of this original form was changed to Dai Mui Fa Kuen 大梅花拳.

Choeng Gong Dai Long Kuen 长江大浪拳, Fist of the Great Waves of the Yangtze. As the name was very long, it was shortened to Choeng Kuen 长拳 or "Long Fist".

On Bong Kuen 安邦拳, "Securing the Nation", which was later called Hung Yan Kuen 洪人拳, Form of the Hung, referring to the Hung Mun 洪門 party, a revolutionary society. In order not to betray their support for the revolution, practitioners of the style changed the name again to Hung Yan Kuen 雄人拳, this time using the character Hung 雄 meaning 'powerful', 'masculine'. This is the form we usually know as Hung Yan Bat Gwa Kuen 雄人八卦拳, or Righteous and Strong Bat Gwa Form.

Man Zoeng Kuen 万象拳, Fist of Ten Thousand Forms, which today is called Dai Bat Gwa Kuen 大八卦拳 or Great Bat Gwa.

Nin Choeng Kuen 年长拳, Fist of the Elder, later renamed Bak Mo Kuen 白毛拳 or White Hair Fist Form.

As far as we know, the Cheong Kuen form is a form originating from the Hung Sing 鴻勝 style of Fóshān 佛山 and does not come from Chan Heung, as it is not found in other lineages of the Hung Sing 雄勝 style of Chan Heung.

On the other hand, according to the tradition of our lineage, the forms Bak Mo Kuen (also called Bak Mo Bat Gwa Kuen) and the form Mui Fa Kuen (also called Mui Fa Bat Gwa) were created by Chan Jiu Chi 陳耀墀, along with the rest of the Bat Gwa.

Deconstructing the myth

The mythology of Choy Li Fut, common to the styles of South China that claim descent from the legendary temple of Southern Shàolín 少林 (Nán Shàolín 南少林), relates Chan Heung and Choy Fook 蔡褔 to revolutionary activities encompassed under the slogan fǎn Qīng fù Míng 反清復明 (overthrow the Qīng and Restore the Míng 明).

According to this mythology, the corruption into which the government of the Qīng dynasty had fallen and the oppression to which it subjected the people justified a subversive struggle, which was seen as just and heroic. In this narrative, the Manchus were presented as the oppressors of the Chinese people, who would yearn for liberation from the Manchu yoke.

However, the anti-Manchu sentiment conveyed in these stories and the widespread hostility towards the government are a product of a date later than the time of Chan Heung and his early disciples.

There are several reasons that support these ideas:

1) Corruption, although widespread and practically pervasive, was often tolerated with an attitude of resignation (for a more exhaustive assessment on this subject, see our article Corruption in Qīng Dynasty).

2) The mythology of the burning of Southern Shàolín first appears in the records of the confessions of members of the Tiāndìhuì 天地會 Society at Chan Heung's time. This secret society, like others, was at the beginning a society of mutual aid and assistance among its members without any political or revolutionary aspect. As these societies were embroiled in inter-clan violence and struggle for local resources, and were known for their beliefs and superstitions, they were persecuted by the government, which was suspicious of sectarian religious groups. It is possible that this same persecution was in fact what turned these societies against the government.

3) Despite the fact that the legend of Southern Shàolín had already been recorded in writing in the founding mythology of these societies, it was not until 1893, the year in which the novel entitled "The Flowering of the Holy Dynasty" (Shèng Zhāo Dǐng Shèng Wàn Nián Qīng 圣朝鼎盛万年青, better known as Everlasting) was published, that there was a boom of stories that reproduced this myth, mainly in the literary genre known as "martial arts fiction of the Canton school" (Guǎng pài wǔ xiá xiǎo shuō 廣派武俠小說). Little by little, the beliefs transmitted by these fictitious stories supplanted historical reality.

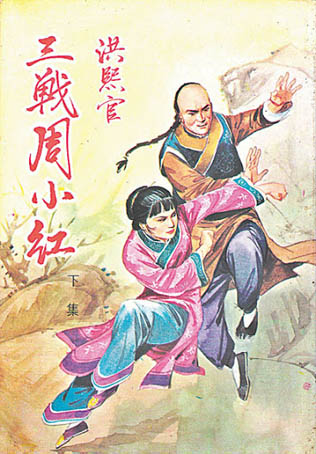

Cover of a martial arts fiction novel.

4) If the Chinese, as a people, had felt oppressed by the Manchus, they could easily have rebelled. Despite the uprisings that took place, the largest of which was the Tàipíng rebellion, the government would not have been able to deal with them without the support of a large popular majority. In fact, despite the fact that at this time the Eight Banner corps (Bāqí 八旗) consisted mainly of Manchus, the Green Standard Army (Lǜyíngbīng 綠營兵) was also active. This was a corps formed exclusively by Hàn 漢 Chinese under the command of Chinese officers subordinate to the regional administration. This army of Chinese, estimated to number three times as large as all the troops of the Manchu Eight Banners, fought against the uprisings in favour of the Qīng dynasty, instead of rebelling.

5) On the other hand, all the corps of the army –Eight Banners and Green Standard Army– numbered at most a few hundred thousand –of which, we reiterate, three-quarters were Hàn Chinese of the Green Standard– while the Chinese population in the mid-nineteenth century is estimated at 430 million. It is understandable, then, that if the Chinese as a people had wanted to overthrow the Manchus, they could easily have done so. From these figures it can be deduced that the dynasty had great popular support.

6) Despite the rhetoric of Míng restoration, and the existence of an anti-Manchu movement in the early days after the Qīng conquest in the seventeenth century, this movement did not have a continuity during the eighteenth century until the nineteenth century. Even though, at the end of the 19th century, there were groups that wished to overthrow the Qīng dynasty, Míng restoration was not at all possible. The anti-Qīng movement would not resurface until the dawn of the twentieth century.

7) Finally, we have already pointed out how the schools of both Chan Heung and his students were operating openly without persecution by the government, and without apparently having suffered any reprisals after the suppression of the rebellion, indicating that they were not perceived with suspicion or felt as a threat to the government.

For all these reasons, the mythology that links Choy Li Fut with rebel movements does not hold up. It is, of course, possible that some practitioners of the style felt sympathy for the revolutionary movements and even participated in them, but in no case does it seem that the Choy Li Fut as an institution, embodied in the different schools that were founded under the influence of Chan Heung, participated in these movements during the nineteenth century —the Fóshān branch will be involved in these movements later, already in the twentieth century.

We therefore understand that this revolutionary rhetoric is the fruit of a few discontented individuals who, in later times, tried to use it to legitimize their political activities and thereby reimagined the past.

We know, too, that secret societies made use of martial arts as a recruiting tool, and through martial arts instruction they transmitted their ideology and beliefs to their students. It is possible, then, that these myths were propagated by this means among the martial arts circles of the time, and took root in the collective imagination.

Sources:

Hamm, John Christopher. Paper Swordsmen: Jin Yong And The Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel, 2005 University of Hawai’i Press.

Dian H. Murray, Qin Baoqi. The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History, 1994 Stanford University Press.

Benjamin N. Judkins, Jon Nielson. The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. University of New York Press, 2015

Wong Doc-Fai, Eight Principal Forms of Choy Li Fut