Introduction

In the time we have been teaching, we have been surprised by the number of people who often come to our school suffering from knee pain, having practiced Taichi.

Taichi (Tàijíquán 太極拳), in addition to being a very useful martial art in self-defense, is also a precious discipline for the cultivation of health and mental balance. But, as can be understood, to enjoy its benefits it is necessary to learn and practice it correctly, since a poorly done Taichi not only will not bring us these benefits, but it can also lead to various injuries.

This is something obvious and yet often overlooked. Taichi is not magic, it is not a panacea that heals by the mere fact of attending a class or by some kind of esoteric principle. Rather, it helps, through a conscientious, constant and prolonged practice, to the correction of bad habits, both postural and mental, and to the maintenance of health through a gentle and very controlled exercise.

We say it again, at the risk of repeating ourselves: through a conscientious, constant and prolonged practice. This is something that unfortunately many people do not seem to be willing to accept; learning takes effort.

It is a pity that such a valuable discipline ends up causing problems, such as knee pain, which are indeed easily avoidable, and often caused by the ignorance of the very instructors who teach it. And it is that Taichi, in its diffusion, has often become another commercial activity, has been emptied of all its depth and its very essence, and has been distorted to such an extent that it is really difficult to find properly qualified instructors.

Taichi and knee pain

As we have said, knee pain is easily avoidable in the practice of Taichi. It is only necessary to follow a couple of recommendations, but the teacher or instructor must be demanding and be aware of the mistakes that their students may make, to correct them properly. Even instructors with knowledge of this art often overlook these mistakes in their students.

The most important points to highlight are the following:

1. The knee of the leg that bears more weight should point in the same direction as the corresponding foot. In the event that both legs support a similar weight, this rule must be applied to both knees.

This point is the most important and, ultimately, the others can be reduced to this one. Its importance is even greater in xūbù 虛步 (empty stance) since, in this case, practically the entire weight of the body falls on one leg.

Correct xūbù. The knee "pushes" toward the tip of the foot.

Incorrect xūbù. Note that the knee "comes in" in relation to the tip of the foot.

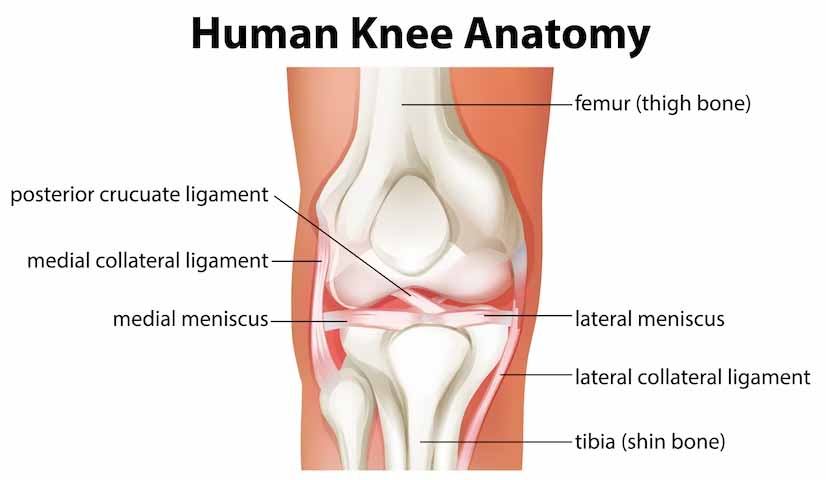

When the knee is not placed in the correct position, the internal ligaments of the knee and the anterior cruciate ligament are stretched. It can cause ligamentous laxity and other problems associated with it, such as crushing of the medial meniscus, knee osteoarthritis due to uneven wear, etc.

(Image credit: Freepik)

To avoid this, you must "push" the knee out until it is above the tip of the foot. Although it is simple to understand, it is difficult for a beginner to realize that he is making such mistake; that is why the instructor or teacher must be very attentive to correct it.

The same applies in sìliùbù 四六步.

Correct sìliùbù.

Incorrect sìliùbù.

2. Another point to consider is the following: in arch stance (gōngbù 弓步) the knee should not exceed the tip of the foot.

At present, the negative effects of this position are disputed. A few years ago it was believed that, if the knee exceeded the tip of the foot, there was too much pressure on it, which could affect the patellar tendon. Today, it is said that this pressure is compensated by the action of the hamstring muscles and hip. In any case, this is a technical error and should be avoided.

Correct gōngbù. The knee is at the height of the toe.

Incorrect gōngbù. Regardless of whether the effects of exceeding the toe with the knee on the health of the latter are considered null, it is a technical error, since the position is more difficult to "retrieve".

Correct gōngbù, front view. The knee is above the tip of the foot.

Incorrect gōngbù. In this case, the position has a negative effect on the knee ligaments, for the reasons specified in point 1.

3. In dúlìbù 獨立步 (single leg stance) it is also important to pay attention to the stability of the knee applying the same principle mentioned in point 1 and, in this case, it is important an adequate progression in training to avoid an injury due to knee instability, when the practitioner does not have sufficiently developed musculature.

4. Finally, another mistake related to knee pain is not keeping the third line principle (chuānzì 川字) when it is due. When the principle of third line is not maintained, stability is lost in the knee and it shakes, causing it to point in a different direction to the tip of the foot, and causing problems similar to those mentioned in the first point.

It is incredible that some Taichi instructors do not even apply this principle themselves, and their positions are unstable and potentially harmful, apart from being absolutely ineffective martially. The principle of third line is basic, and must be learned from the first day one starts in this discipline.

With these statements we do not intend to offend anyone, but simply to warn of the importance of finding a serious school and a qualified instructor when one wants to start in Taichi. In our school we pride ourselves on the fact that, in the time we have been teaching, no person who has started with us suffers from this ailment.

On the other hand, it is important to note that these errors do not automatically produce a knee injury, but that the injury occurs when the error becomes a habit. That is, the isolated execution of a bad posture does not usually lead to injury, but its continued repetition probably will.

Finally, it should also be noted that, if someone has a condition of knee injury, prior to starting in Taichi, they should consider whether this is really an activity appropriate to their condition.

Some doctors recommend Taichi without ever having practiced it or having the slightest idea of what it is. And keep in mind that Taichi, despite providing certain more immediate benefits (relaxation, calm, gentle exercise...), needs a fairly long learning time (often several years) to lay a minimum foundation and be able to start getting all its benefits. Therefore, if you are interested in this discipline, do not wait until you are older or have an injury to start, because then it may be too late.

Health and good practice!

2 thoughts on “Taichi and Knee Pain”

Hi, thank you very much for this post. What is chuānzì 川字 ? I cannot find reference to it anywhere. Maybe it also has another name?

Hi Alex,

Thank you for your comment.

Regarding your question, chuānzì 川字 is a concept that relates to the distance that separate both feet in width.

The name is not meant to be translated literally, since chuān 川 here refers to the shape of the Chinese character and not to its meaning. Therefore, in my language (Spanish) we call it “third line”. I am not sure if it has a specific name in English (I am only aware of the original Chinese name).

So, basically, it means that both feet should be separated more or less by the width of the hip (left-right separation, not front-rear separation). So they are not standing on the same straight line or on the center line. So in the character chuān 川, the middle stroke is meant to be the centerline, and the left and right strokes are the lines on which both feet stand. This principle applies only to some stances, like bow stance, where weight is distributed on both feet. Not on “empty stance”, for example, where the rear leg holds all the weight.

I explained it as best as I could with my English, although is very easy to understand when you look at the posture directly.

Hope it helps.

Kind regards,

Juan