The Lántíngjí Xù 蘭亭集序 ("Preface to the Collection of Poems of the Orchid Pavilion") is a short text considered one of the masterpieces of Chinese calligraphy. It is a preface written as an introduction to a collection of poems composed in a place known as "Orchid Pavilion" (lántíng 蘭亭). His somewhat curious story is related to wine and poetry. Let's get to know it.

The story behind the Lántíngjí Xù

In the spring of 353, a purification ritual (修禊 xiūxì) was held, bringing together several dozen scholars and literati of the time in a place called Lántíng 蘭亭 (Orchid Pavilion), in present-day province of Zhèjiāng 浙江. The ceremony was presided over by Wáng Xīzhī 王羲之, who, in addition to being a government official at the time, was a famous writer and calligrapher.

Portrait of Wáng Xīzhī 王羲之.

During the celebration, forty-two literati decided to participate in a poetry contest (鬥詩 dǒu shī), a common pastime among the scholars of the time. There were several forms of poetic competition, which involved the intake of wine, and which were practiced at banquets and gatherings for fun.

On this occasion, the type of contest chosen was the so-called liú shāng qū shuǐ 流觴曲水 ("floating cup on a winding brook"). Participants sat on the edge of a brook, and someone upstream was leaving in the stream cups of wine, made with lotus leaves, floating in the water. When one of those cups stopped on the shore in front of a participant, that person had to compose a poem on the spot, or else drink the wine from the cup.

Illustration of the scene: the scholars, on the banks of the brook, composing poems, and the cups floating downstream.

That day, 26 of the participants composed a total of 37 poems, which those gathered there decided to collect in a written collection. Excited, the poets asked Wáng to write a preface as an introduction to the collection of poems.

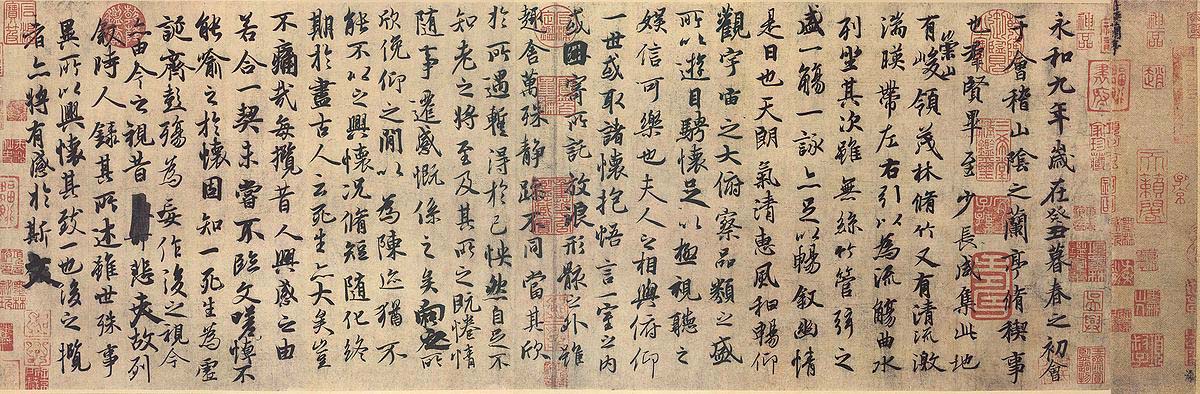

Wáng, drunk like the others, prepared a piece of paper, took the brush and wrote the so-called Lántíngjí Xù, consisting of three hundred and twenty-four characters written in semi-cursive style (行書 xíng shū), which express the pleasure of encounter, at the same time as melancholy feelings about the fleetingness of life.

The piece, being improvised, contained crossed-out words and corrections of certain characters. The next day, Wáng, sober, wanted to rewrite the preface on a new sheet, so that it would be cleaner. However, no matter how much he tried, he did not get his calligraphy to match that of the previous day in a state of intoxicatedness. So the Lántíngjí Xù remained as Wáng had written it on the day of the celebration, with its corrections and everything. And, despite containing these corrections, the work is considered a masterpiece, the pinnacle of semi-cursive Chinese calligraphy.

Loss and replicas of the Lántíngjí Xù

Unfortunately, the original Lántíngjí Xù is lost. In fact, not even a single piece of the calligraphy of Wáng Xīzhī, perhaps the most famous Chinese calligrapher, has survived to this day. All that remains are replicas of later artists, who imitated Wáng's calligraphy based on his original works, before they were lost.

It is believed that Emperor Tàizōng 太宗 of the Táng 唐 dynasty, a great admirer of Wáng Xīzhī, managed to take over the original Lántíngjí Xù and that, after his death, he was buried with it.

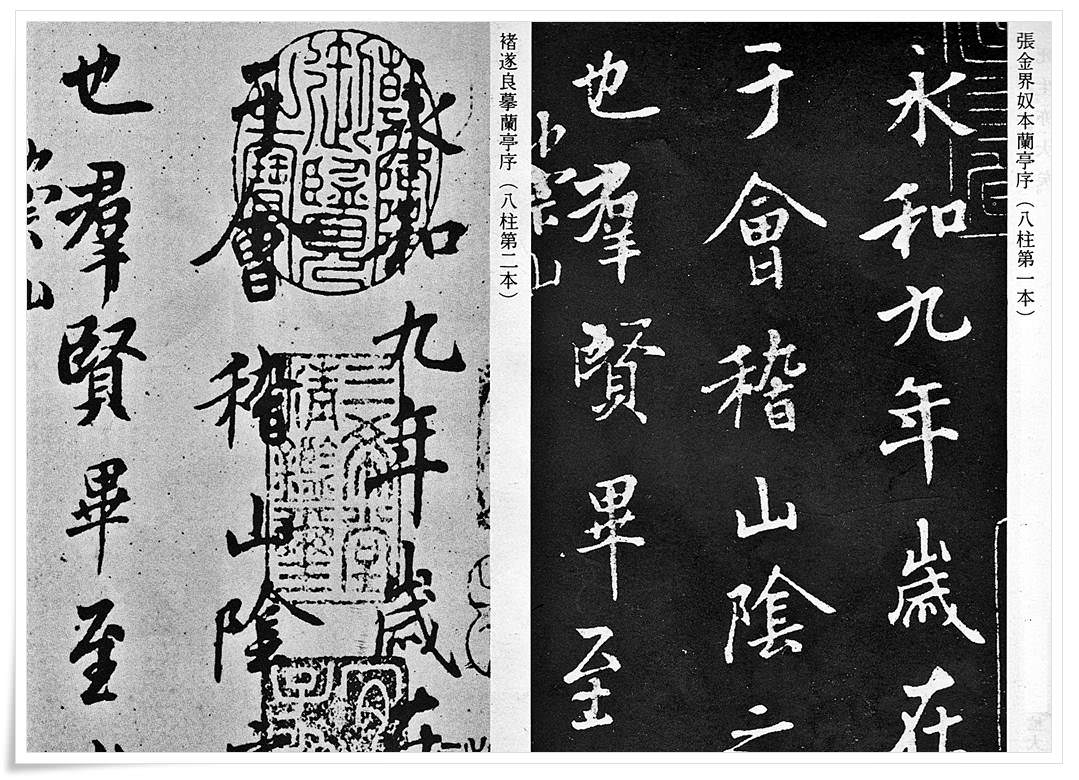

Today's replicas of the original preface are the work of later great masters of calligraphy, such as Féng Chéngsù 馮承素, Ōuyáng Xún 歐陽詢, Zhǔ Suìliáng 褚遂良 and Yú Shìnán 虞世南. Féng was a copyist of the royal court and his work is believed to be the most accurate copy of the original. The method he used to recreate Wáng's work is similar to tracing.

Copy of the Lántíngjí Xù 蘭亭集序 by Féng Chéngsù 馮承素, considered the closest to the original.

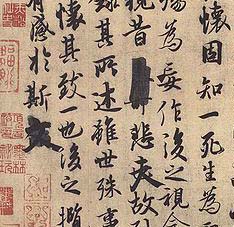

Detail. Note the corrections in certain characters, which have also been reproduced in the replica.

Detail of the replicas by Zhǔ Suìliáng 褚遂良 (left) and Yú Shìnán 虞世南 (right).

Conclusion

It is said that Wáng tried to rewrite his preface more than a hundred times, but none of them satisfied him as much as the original. This shows the importance that in calligraphy is given to the mental/emotional state of the artist at the time of production of the work.

The feelings that inspired Wáng to produce his masterpiece, the company of friends, the euphoria of wine, and the jovial atmosphere were no longer present when he tried to rewrite it.

Below are transcribed, to finish, a few lines of the Lántíngjí Xù, with pīnyīn 拼音 phonetics and an approximate translation.

當其欣於所遇,暫得於己,怏然自足,

dāng qí xīn yú suǒ yù, zàn dé yú jǐ, yàng rán zì zú

When we find pleasure, we are momentarily satisfied

不知老之將至。

bù zhī lǎo zhī jiāng zhì.

but I get old without realizing it.

及其所之既倦,情隨事遷,感慨係之矣。

jí qí suǒ zhī jì juàn, qíng suí shì qiān, gǎn kǎi xì zhī yǐ.

When I consider where I've come to, I sigh with unease,

向之所欣,俛仰之間,已為陳跡,

xiàng zhī suǒ xīn, fǔ yǎng zhī jiān, yǐ wéi chén jì,

Joys belong to the past,

猶不能不以之興懷;

yóu bù néng bù yǐ zhī xīng huái;

we can only long for them;

況修短隨化,終期於盡。

kuàng xiū duǎn suí huà, zhōng qī yú jìn.

The length of our life is unknown, but it always ends.