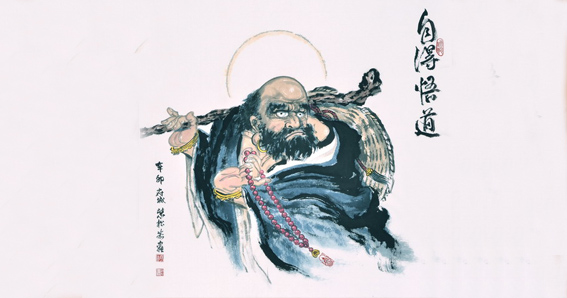

Bodhidharma, known in China as Pútídámó 菩提達摩 or Dámó 達摩, was an Indian monk who came to China in the 6th century, and is usually considered as the founder of Kung Fu and Chán 禪 Buddhism.

Although historical records on Bodhidharma are contradictory (we will see this in a forthcoming article), we want to expose here his life as it has become part of the popular imagination.

According to tradition, his birth name was Jayavarman, being Bodhidharma his Buddhist name, and he was the third son of an Indian king. If this was true, he would have thus belonged to the Indian caste of the Kshatriyas, the warrior caste. However, he decided to take the Buddhist vows and become a monk and eventually travel to China to propagate the Buddha's teachings.

Bodhidharma as the Patriarch of Chán

Buddhism had penetrated China through the Silk Road from India and at the beginning of 6th century was already a consolidated religion throughout the Empire. However, when Bodhidharma arrived in China in the year 520, he found a very ritualized Buddhism, which put a great emphasis on the study of the scriptures, ceremony and cult.

For Bodhidharma, the path to realization was based on the practice of meditation, above ritual, for what was known in China as Chánnà 禪那, or simply Chán 禪, a term derived from the original Indian word dhyāna, meaning 'meditation' or 'contemplation'. Chán did not begin to take shape as a separate school until the end of the 6th century, and later it extended to Japan, where it acquired the name by which it is known today in the West: Zen.

In China, Bodhidharma is considered the first Patriarch of Chán and the twenty-eighth Patriarch of Buddhism, that is, in a lineage of disciples in direct line from the Buddha Gautama. However, it is possible that this genealogy was invented much later, during the 7th and 8th centuries, in response to the criticisms received by the Chán School by other Buddhist sects. These criticisms sought to undermine the growing popularity of Chán in China, alleging that there were no records to demonstrate its direct transmission from the founder and that, therefore, the school lacked authority.

According to popular belief, shortly after arriving in China, Bodhidharma was invited to an audience with Emperor Wǔdì 武帝 of the Liáng 梁 dynasty, a fervent Buddhist devout who had spent large sums of money in the construction of temples and monasteries.

Emperor Wǔdì 武帝

Bodhidharma's encounter with the Emperor

During his meeting, the emperor asked Bodhidharma, proudly:

— Since I ascended to the throne, I have built many temples and monasteries and translated scriptures, how great is my merit for these acts?

To his surprise, Bodhidharma responded sharply:

— Absolutely no merit.

The Emperor was greatly irritated to hear this, but he still continued enquiring the monk about the nature of Buddhism:

— What, according to you, is the essence of Buddhism?

— There is no essence, just vast emptiness. — This response from Bodhidharma angered the emperor again.

— Then, who is the person I have in front of me?

Faced with this new question, Bodhidharma simply replied:

— I don't know.

The Emperor was very disappointed with his encounter with Bodhidharma, of whom he expected great praise for his patronage of Buddhism, and dismissed the monk. He did not understand that, for Dámó, the realization of acts of transitory nature moved by desire to acquire merit and popularity were not something worthy of mention, and that the true merit lay in the search for enlightenment and true understanding through meditation.

Bodhidharma's words to the emperor are too profound to be explained. Bodhidharma speaks of emptiness not as a concept but as an experience. In China, Buddhists were too busy debating the scriptures and concepts like the Four Noble Truths. But the practice of Chán leads to the realization that all things are deprived of essence, of an independent self. For the Indian monk, this was not a question that could be reached through rational understanding, through concepts or words, but through the experience of meditation. The Emperor was filled with these concepts that clouded his mind and distracted him from his own experience.

Finally, his answer to the emperor's last question is that of someone who has emptied himself of concepts and ideas. Therefore, Bodhidharma cannot answer that question.

It is said that, after having dismissed Bodhidharma, Emperor Wǔdì regreted it and wept bitterly.

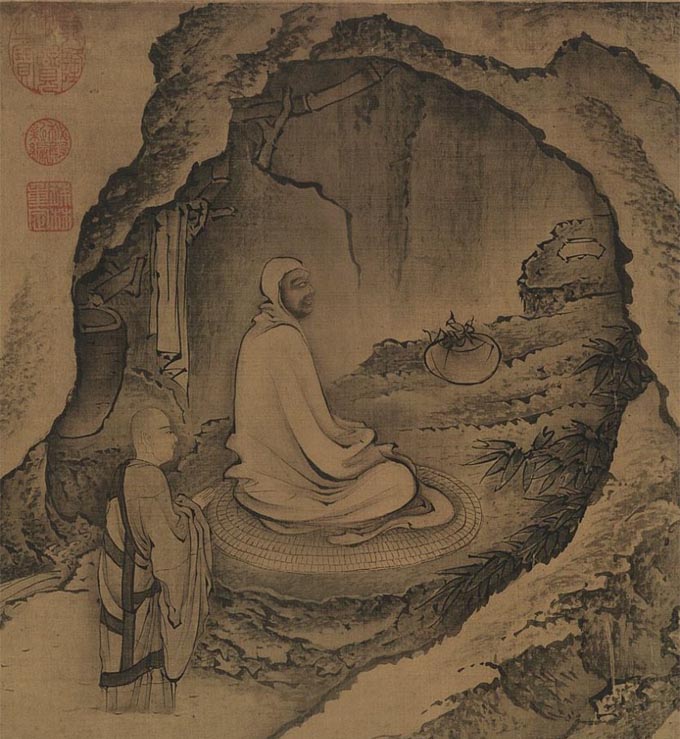

Bodhidharma in Shàolín 少林

After meeting the emperor, Bodhidharma traveled north, near Luòyáng 洛阳, to Mount Sōng Shān 嵩山, where the Shàolín 少林 monastery is located. According to the popular legend, after being denied access to the monastery, he settled in a nearby cave, where he spent nine years, without interruption, sitting in meditation in front of a wall. It is said that during that time he never spoke to anyone, even though many of the monks visited the cave to see him.

There are many legends concerning this period of his life. One of them tells how Bodhidharma, after falling asleep while meditating, cut off his eyelids so as not to sleep again; this is why he is always represented with huge eyes, without eyelids. From his eyelids, which he threw to the ground, the first tea-plants germinated; since then, the brew made of this plant keeps the monks awake during meditation. Of course, tea was already consumed in China for hundreds of years, perhaps even millennia.

Bodhidharma is represented without eyelids

Another of these legends says that a monk begged Bodhidharma to accept him as a disciple, to which he refused. The monk repeatedly insisted and Bodhidharma ended up telling him that he would agree to teach him when the snow covering the entrance to the cave turned red. Upon hearing this, the monk cut off one of his arms, and his blood turned the snow at the entrance red. That's how Bodhidharma began to teach Chán.

Some versions of the myth say that Bodhidharma died in the cave, sitting in meditation. But the most widespread one says that, after nine years of meditation, Bodhidharma was accepted into the Shàolín monastery, where he taught Chán Buddhism. According to popular belief, as the monks spent long hours in meditation and their limbs were atrophied, Dámó taught them a series of physical and Qì Gōng 氣功 exercises to keep them fit, which over time gave rise to the martial arts of Shàolín.

After several years of teaching, Bodhidharma felt the desire to return to India. To test his disciples, he asked them to say something to prove that they had understood his teachings. One after another they were stepping forward and uttering profound words, until one of them approached, bowed, and simply remained silent. It was to this monk whom Bodhidharma chose as his successor. He was called Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 and is considered the second Patriarch of Chán, and the twentieth ninth from the Buddha.

It is not known if Bodhidharma returned to India, but there is a legend according to which he died in China. Some time after his death, he was seen on his way to his native land, barefoot and with a single sandal hanging from his staff. After exhumed his tomb, the monks found it empty, except for one sandal.