Introduction

At the end of the eighteenth century, the China of the Qīng 清 dynasty was one of the most advanced and powerful nations on the planet. For more than a hundred years, the country had enjoyed a period of economic and cultural splendour, which allowed massive population growth and the flourishing of arts. Their material culture and standard of living were the highest in the world. Emperor Qiánlóng 乾隆himself would write to the King of England, in response to an English embassy, that the Chinese nation produced all the products it could need and did not want anything from foreign nations1.

Qiánlóng 乾隆.

But this would change radically in the following decades, almost overnight. Industrialization was advancing in Europe by leaps and bounds, especially with regard to military technology, and the balance of power in the world shifted to the Western side.

The decline of the Qīng dynasty began drastically in the Opium Wars (Yāpiàn Zhànzhēng 鴉片戰爭) and precipitated even faster until the Boxer Rebellion (Yìhétuán Qǐyì 義和團起義) and with new humiliations at the hands of the industrialized powers of the West and, this time also, of Japan, challenging the regime's own legitimacy. unable to adapt to the times.

The fall of the dynasty in the early twentieth century would mark the end of an imperial era of more than two thousand years.

Historical context

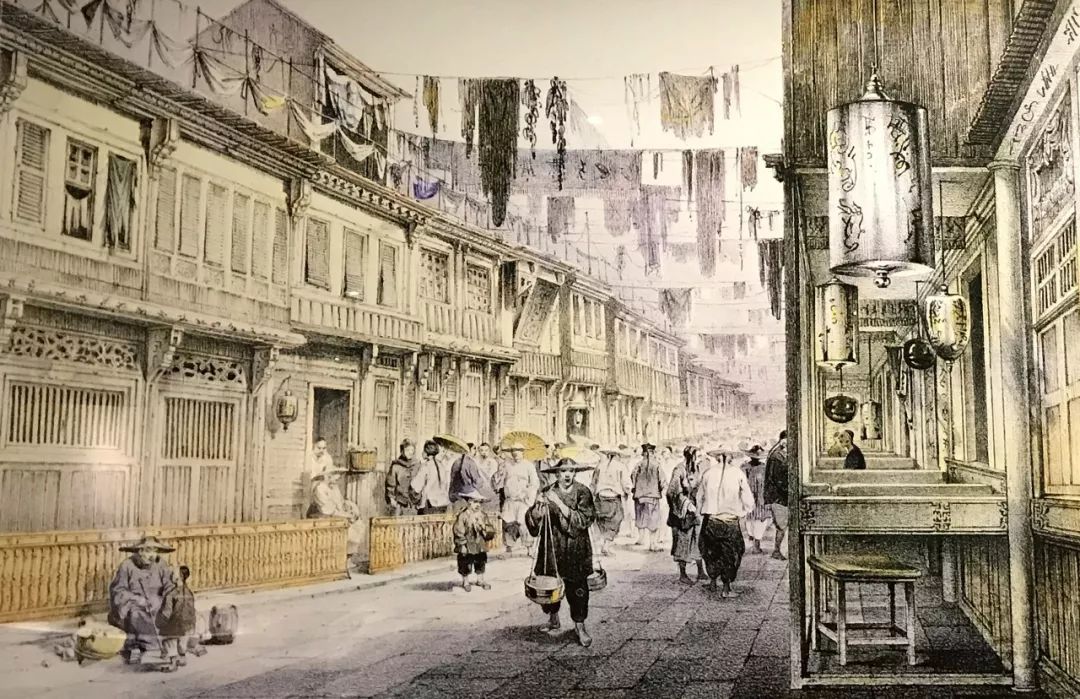

To talk about the Opium Wars we first have to talk about China's trade with the West. At that time, all of China's trade with Western nations was regulated according to the Canton System, known in China as yīkǒu tōngshāng 一口通商, "trade relations through a single port".

This system, implemented in 1770, was intended to regulate trade relations with Western merchants, which until then had operated only on trade routes between countries in the region, and which now offered the possibility of direct trade with the West and India.

The Canton System allowed foreigners to trade with China only through merchants with an official license issued by the government (cohong/gōng háng 公行), operating in the port of Guǎngzhōu 廣州 (Canton).

Painting depicting the streets of Guǎngzhōu 廣州.

Current photograph by Guǎngzhōu.

It should also be noted that at the heart of this system lay a difference in the understanding of international relations. While the Qīng empire was based on a tributary system, and thus had a hierarchical concept of these relations, Western governments were eager to establish diplomatic relations with China on an equal base, and demanded European-style relations, through consuls, ambassadors, and trade treaties.

Of all the products demanded by Britain, tea was undoubtedly the most important of them. When the British began to consume tea from China, it quickly became the British national drink.

Tea imports grew in England from 180 tons in 1720 to 10,500 tons in 1800. At that time, the tea trade was one of the main sources of revenue for the British state through the taxes imposed on the import of the product.

However, the commercial interests of the two countries were very different. While the British wished to acquire, in addition to tea, an endless number of Chinese manufactures such as silk or porcelain; the Chinese, on the other hand, were not as interested in Western products and demanded payment in silver in exchange for their goods. In turn, the Canton System prevented Westerners from accessing tea-producing regions, where they could get the product at lower prices.

Under these circumstances, the British government's coffers were being emptied of silver, which was flowing into China from three million ounces in the 1760s to 16 million ounces in the 1780s. The British needed to reverse the influx of silver and eventually came across a commodity whose demand was on the rise at the time among the Chinese: opium.

Opium

Before the importation of opium by the British, the drug had been used in China for more than a thousand years as a medicine, by ingestion.

The custom of smoking opium postdates the discovery of tobacco in the Americas, and seems to have first appeared in Taiwan in the 1620s, spreading from there to the Chinese provinces of Fújiàn 福建 and Guǎngdōng 廣東.

However, the opium consumed by the Chinese until the eighteenth century was not a pure substance but adulterated with tobacco, known as madak (màndákè 曼達克), which had approximately 0.2% morphine, and was used for its therapeutic properties to relieve pain and stress. However, many Chinese had already developed an addiction2 to madak and, in 1720, the Qīng government, considering it a problem for society, banned its use.

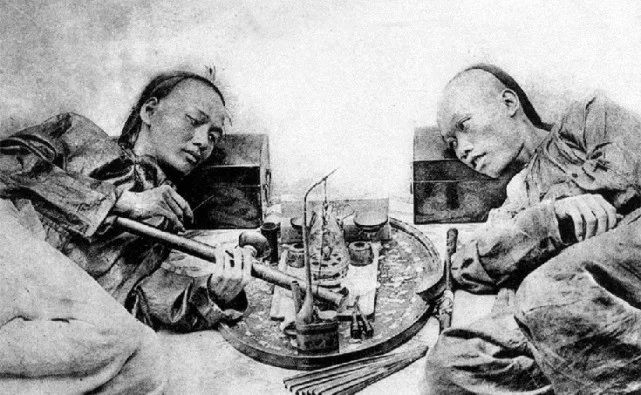

In contrast, opium introduced by England was an unadulterated substance, with a higher morphine content and addictive potential. Its consumption produced alterations of the respiratory system; it slowed the heart rate and slowed down metabolism. Once the habit was acquired, withdrawal syndrome caused cramps and trembling, shivers, vomiting, diarrhea, nausea and other gastrointestinal problems.

Men smoking opium.

Consequences of the opium trade

In the late eighteenth century, the East India Company produced opium in Bengal for introduction into China. As the importation of the drug was prohibited by the Qīng government, the company sold it to private traders, who in turn used the profit generated to pay for the company's trade in tea.

The introduction of opium into Canton gradually increased from 200 chests in 1729, reaching 4,500 in 1800, and skyrocketed at the beginning of the nineteenth century to 40,000 chests in 1839. It is estimated that this amount could supply about two million consumers.

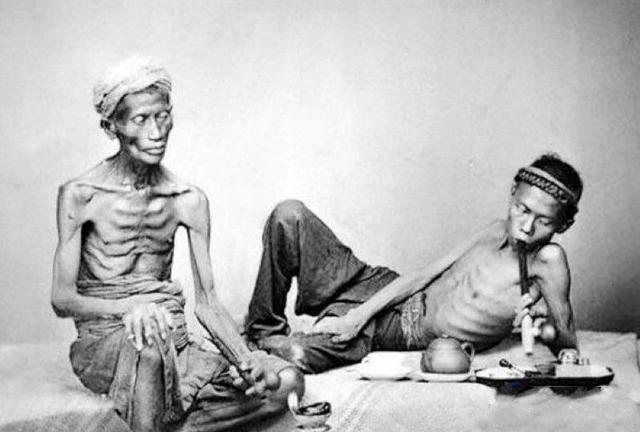

According to official historiography3, the social consequences of the opium trade were, mainly, a generalized addiction, with the damage to health that it entails, and a worsening of the effectiveness of the labour and military force of the population as a result of the former.

Although addiction in the general population is estimated at 0.6%, its incidence was much higher in certain social segments. It is estimated to have affected 10-20% of central government officials, 20-30% of provincial government officials, and up to about 50% among mùyǒu 幕友 (local government councillors or private assistants).

Opium consumption also spread among Manchu military cantonments, and among the imperial guard and palace eunuchs.

Opium addiction wreaked havoc among the population.

But the consequences of the opium trade also had important economic dimensions. The silver that had entered China to pay for tea now came out in exchange for opium, despite the government's ban on exporting silver (and also, despite the prohibition of opium itself). The amount of silver paid for the drug increased from two million taels a year in 1820 to nine million in 1830.

Although taxes were stipulated in silver, peasants paid their value in copper. And, as there was less silver, the price of it increased. Consequently, the amount of copper that peasants had to pay increased drastically, without the central government increasing its income.

Opium itself became a currency. Western merchants were not the only ones to make a profit. Chinese merchants also profited from this trade, as well as police officers who were bribed to smuggle the drug.

A long smuggling network was established, from the mouth of the Pearl River (Zhū Jiāng 珠江), through canals, to the Yangtze (Cháng Jiāng 長江) and thence to northern China. With smuggling, corruption increased and spread to senior government officials, who often confiscated a few chests of opium to pretend to do their job, while letting many more pass in exchange for bribes.

Although both the British public and missionaries based in China were against the opium trade, the British government consented to it. After all, its profits paid for tea that produced substantial income for the crown. The Chinese government itself maintained for a long time a rather lax nominal ban that translated, in practice, into permissibility, and only attempted to enforce the ban from the 1820s onwards.

The First Opium War

Faced with this situation, the Chinese government finally decided to curb the opium trade. In December 1838, Emperor Dàoguāng 道光 appointed an imperial commissioner to be sent to Canton with the mission of ending smuggling.

Commissioner Lín Zéxú 林則徐 arrived in Canton in March 1839, and made great progress in the fight against opium. He set up sanatoriums to treat addicts, arrested thousands of Chinese smugglers and confiscated goods. His efforts succeeded in creating great difficulties for British merchants, who could not sell their opium shipments even at low prices.

Lín even wrote a letter to Queen Victoria appealing to her sense of morality and decency, asking her country to stop bringing opium into China. But the West wanted unfettered open trade.

On March 24, 1839, Lín's men surrounded thirteen western warehouses, holding some 350 hostages until they handed over their opium shipments. In front of their own eyes, he destroyed more than a thousand tons of the drug.

Commissioner Lín Zéxú 林則徐.

Lín tried to force the Westerners to sign an agreement by which they promised not to trade in opium and, if necessary, to be prosecuted and tried under Chinese law.

The negotiations reached an impasse, and Lín blocked access to the ports of Canton and Macau for Western ships, leaving their crews without access to water or provisions, in order to force them to sign the agreements.

Finally, violence broke out on September 4, and British ships docked in Hong Kong 香港 in search of provisions. In April 1840, the English parliament, at the request of merchants in China, decided, albeit narrowly, to send troops from India. It was the beginning of the first Opium War.

The result was a crushing defeat and terrible humiliation for the Qīng. The war ended up in August 1842, when British ships, making use of their naval and armament superiority, went up the Yangtze to Nánjīng 南京 and threatened to bombard the city.

Emperor Dàoguāng had to accept the conditions imposed. Lín Zéxú was made the scapegoat, blamed for starting the war and condemned to exile.

The conditions that Westerners imposed on China were registered in the Treaty of Nánjīng (Nánjīng Tiáoyuē 南京條約), considered by China one of the so-called "unequal treaties" (bù píngděng tiáoyuē 不平等條約). Among these conditions were the cession of Hong Kong and the opening of the ports of Canton, Fúzhōu 福州, Níngbō 宁波, Xiàmén 廈門 and Shànghǎi 上海 to Western merchants, missionaries and consuls; the abolition of the Cohong monopoly, the reduction of taxes on export products, the right of extraterritoriality and, in addition, a compensation of 21 million silver dollars.

Opium trafficking, although not legalized, continued throughout the nineteenth century, reaching two hundred thousand chests annually.

Signing of the Treaty of Nánjīng (Nánjīng Tiáoyuē 南京條約).

Later conflicts

But the conflicts did not stop after the concessions of the Treaty of Nánjīng. In the 1850s, while the Qīng government was busy facing the bloodiest rebellion in its history, England and France launched a joint campaign that ended with the occupation of Běijīng 北京 in 1860 and the burning of the Summer Palace.

Through these attacks, China was forced to sign new treaties. The Treaty of Tiānjīn 天津 (Tiānjīn Tiáoyuē 天津條約) legalized the opium trade, paid new compensations, opened new ports to trade, forced the Chinese to buy European goods, and allowed Western missionaries to preach throughout the country.

The European powers obtained the right to establish legations and consulates, open factories on Chinese soil, and some areas were leased to them in perpetuity.

The end of opium consumption

According to Western observers, in the late nineteenth century, about one-tenth of the Chinese population smoked opium. In 1880, its import decreased due to the development of local crops. Its consumption continued in China for half a century and was not definitively eradicated until the seizure of power by the communist government in 1949.

Conclusion:

The Opium Wars were the result of a series of events that originated in errors due to ignorance and lack of understanding between the two cultures, rather than a succession of malicious acts. Its causes are complex and impossible to explain in a few pages.

While it is true that British merchants had no qualms about illegally trading opium, it must also be understood that this trade was not born of an evil intention to poison the Chinese people, as the official story has wanted to understand, but of a demand that already existed and increased over time. For every British merchant who introduced opium, there was a Chinese smuggler who acquired it and took care of its transport and distribution in China.

The British were not the only foreigners to trade in opium. The Americans did the same, and although they did not get involved in the first war, they benefited greatly from it, despite officially remaining against it.

Finally, the Opium Wars were not known by this name in China during the nineteenth century. It was only after the fall of the dynasty in the 20th century that Chinese historians began to adopt this name, which over time would become a key piece of Chinese nationalism and its struggle to strengthen the nation against the imperialist powers of the West.

To understand this conflict in depth, we recommend the book "Imperial Twilight", by Stephen R. Platt, cited in the "Sources" section below.

Notes:

1 This was not strictly so, although Qiánlóng wanted to make him believe it. China imported textiles such as cotton and certain Western products considered luxurious, such as watches, from the British empire, which were fashionable among the upper classes, although it is true that these products were not essential for the country.

2 The problem of opium and addiction is currently being discussed by numerous historians, as we will see in a future article.

3 Again, many historians have debunked this official story, emphasizing that the custom of smoking opium would have spread from the upper classes to the lower classes, and not the other way around.

Sources:

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press, 2010

Stephen R. Platt, Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2018