Introduction

Sūn Wùkōng 孫悟空 is the main character of the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West (西遊記 Xī Yóu Jì), one of the four most important works of Chinese literature.

The Xī Yóu Jì tells a fictional story based on the travels of Xuánzàng 玄奘, a historical monk of the Táng 唐 dynasty who undertook a long pilgrimage to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. In Journey to the West, Xuánzàng is accompanied by four immortal disciples who help him in all kinds of adventures using their supernatural abilities. These disciples are: a hog named Zhū Bājiè 豬八戒 (Wùnéng 悟能), a sand demon named Shā Sēng 沙僧 (Wùjìng 悟淨), a dragon in the form of a horse, Bái Lóng Mǎ 白龍馬, and the well-known Wùkōng, also known as Monkey King, or Handsome Monkey King (Měi Hóu Wáng 美猴王).

Of all the characters in the novel, it is undoubtedly Sūn Wùkōng who has the most prominence, eclipsing even his own master.

Sūn Wùkōng 孫悟空.

Wukong in the Xiyouji

In Journey to the West, Sūn Wùkōng is born from a rock nourished by the Five Phases (wǔxíng 五行) and devotes himself to the study of Dào 道 until he acquires immortality and supernatural powers. After that, the Monkey King travels to Heaven where he causes chaos through his quarrels and mischief.

When it seems that no deity can stop him, Buddha gives him a lesson and buries him under the Mountain of Five Phases (Wǔxíng shān 五行山), where he remains confined for five hundred years until the bodhisattva Guānyīn 觀音 converts him to Buddhism and orders him to follow Xuánzàng (also called Tripitaka, Sānzàng 三藏) to protect him on his journey, giving him the religious name of Wùkōng ("He Who Awakens to the Void"). In the novel, Wùkōng is undoubtedly the most charismatic character, and often instructs his own master in Buddhism.

Wùkōng is characteristic for his "cloud summersault", his iron rod that grows at will and his multiple transformations, among other supernatural powers acquired through meditation and inner alchemy, with which he faces all kinds of monsters to clear the way for his master on the journey.

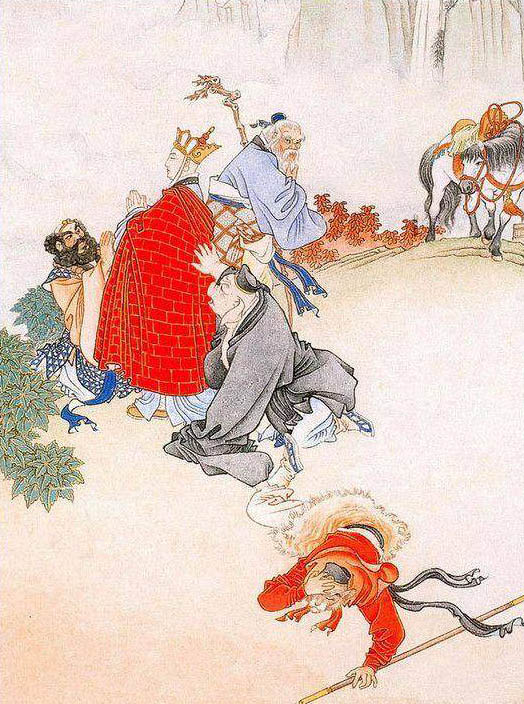

Scene from Journey to the West.

However, this odd monkey-character is not an original invention of the author of the Xī Yóu Jì, but we find several literary antecedents that were gradually shaping his image until culminating in the character of this work.

First, it is worth highlighting the existence of previous works that already narrated fictional stories about Xuánzàng, in which the "disciple-monkey" already appears.

Second, we will examine various Chinese and foreign stories and legends (especially the Ramayana), which could give rise to the legendary figure of the monkey-disciple.

1) Works of fiction about Xuánzàng antecedents to Xī Yóu Jì:

It is worth highlighting two previous works that already narrated a fictional story about Xuánzàng's travels:

- Poetic History of the Acquisition of Scriptures by Tripitaka of the Táng Dynasty (大唐三藏取經詩話 Dà Táng Sānzàng Qǔjīng Shī Huà)

- New Record of the Acquisition of Scriptures by the Master of the Law, Tripitaka, of the Táng Dynasty (新雕大唐三藏法師取經記 Xīn Diāo Dà Táng Sānzàngfǎshī Qǔjīng Jì)

Both works date from the thirteenth century, and constitute the first examples of popular fiction in China. It is clear that by then the real story of Xuánzàng had already entered fiction. However, these works do not yet reach the complexity of Journey to the West.

In these works, a monkey-disciple (猴行者 hóu xíngzhě) already appears, disguised as a scholar with white robe, who, like in the Xī Yóu Jì, earns himself the title of dà shèng 大圣 ("great sage").

In later literary accounts, the monkey character gradually gains popularity until in the Xī Yóu Jì completely monopolizes the prominence over his master.

2) Indigenous and foreign legends

The Ramayana is one of the most important works of Indian Hindu literature, dating from the third century BC. It is a monumental epic that recounts the journey of the hero Rama to rescue his wife Sita from the clutches of the demon Ravana. In his adventures he is assisted by the white monkey god Hanuman, one of the most important deities of the Hindu pantheon.

Undoubtedly, many have seen in the Hanuman of the Ramayana the possible origin of the Wùkōng of the Xī Yóu Jì. However, references to Ramayana in Chinese folk literature are fragmentary and modified. Some authors (Dubridge, Wu Xiaoling) see as unlikely that the author of the Xī Yóu Jì had contact with them. Despite this, the parallels between Wùkōng and Hanuman are too many to ignore: their supernatural powers, their courage in combat, the use of the iron rod as a common weapon, the great leaps through the air or their multiple transformations.

Representation of Hanuman in the Cambodian temple of Angkor Wat.

Hera S. Walker proposes in her study Indigenous Or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong that the influence of the Ramayana on the Xī Yóu Jì would not have been direct, but indirect. That is, that the Ramayana would have influenced certain aspects of Chinese popular culture, and that in turn these aspects influenced the formation of Journey to the West. In this way, Sūn Wùkōng is presented as the product of indigenous and foreign influences at the same time.

Indian civilization, through trade routes, would have passed on the tradition of Rama, in the same way that it has exerted influence on the religion and arts of many Southeast Asian countries. However, this influence would have been less in China, since there was already a powerful local culture independent of that of its neighbors.

Wùkōng would thus be based on an amalgam of both foreign and local elements. Among the local legends that possibly influenced the formation of Wùkōng, Walker highlights the following.

The Cult of White Gibbons in the Kingdom of Chu

Gibbons, especially those of white color, were worshipped in the ancient kingdom of Chǔ 楚 (700-223 BC), in the Yangtze (长江 Cháng Jiāng) basin, which regarded the animal world as equal to human society.

Later, Taoism considered these gibbons as possessing a hidden knowledge of inhalation of qì 氣, as well as magical powers among which was the ability to assume human form and to live several hundred years.

Over time, these characteristics were associated with the more ambiguous figure of the "white monkey" (白猿 bái yuán).

White gibbon.

Sichuan's white ape legend

In Sìchuān 四川 province there was a local version of the myths about the "white monkey", which represent a primitive version of the Táng tale Bǔ Jiāng Zǒng Báiyuán Zhuàn 補江總白猿傳, "Supplement to Jiang Zong's Tale of the White Ape" (see below). This topic, along with that of "Yǎng Yóujī 養由基 shooting a white ape" are common in artistic representations in Sìchuān and formed the basis on which the two main themes of monkey legends developed: the first, an evil monkey who kidnaps women; and the second, the god Èrláng 二郎 defeating a monkey-spirit (note that in the Xī Yóu Jì it is precisely Èrláng who defeats Wùkōng in chapter 6).

Èrláng 二郎.

Supplement to Jiang Zong's Tale of the White Ape

Supplement to Jiang Zong's Tale of the White Ape is an anonymous work belonging to the genre known as chuánqí 傳奇 (short legendary stories), developed during the Táng Dynasty.

This work tells the story of a white monkey who, in times of the Liáng 梁 dynasty, kidnaps the wife of General Ōuyáng Hé 歐陽紇 while he is on campaign in the south in an expedition led by a certain Lìn Qīn 藺欽. After learning of the kidnapping, the general and his soldiers go out to find the ape's lair in the mountains and when they find it they realize that, together with the general's wife, the ape holds many other women captive. After repeated attempts they finally manage to defeat the monkey-spirit through a stratagem and, before dying, he reveals to the general that his wife is pregnant, and begs him not to kill the creature. After the ape's defeat, Ōuyáng Hé returns victorious with his wife and the rest of the women. The story ends with the birth of a child, whose name is not mentioned, who after the death of General Ōuyáng is adopted by Jiāng Zǒng 江總 and will become a famous calligraphist.

Ōuyáng Hé was a real person, father of the famous calligrapher of the Táng dynasty, Ōuyáng Xún 歐陽詢 (557-641). It is believed that the name of Lìn Qīn 藺欽, who in the Supplement is named as the leader of the expedition, is actually an erroneous reference to Lán Qīn 蘭欽, who led an expedition to the south at that time. However, it is impossible that Ōuyáng Hé took part in that expedition, as he was only ten years old at the time, and the person who accompanied Lán Qīn was actually Ōuyáng Wěi 歐陽頠, Hé's father.

Although the title of the work, Supplement to Jiang Zong's Tale of the White Ape, suggests that Jiāng Zǒng, adoptive father of Ōuyáng Xún, had previously written a Tale of the White Ape, historians believe that this work never existed. Actually, it seems that the author of the Supplement would have written it as a personal attack on Ōuyáng Xún, who was known for his ugliness, as well as for his great intelligence, suggesting that his father was actually a monkey.

It is possible that we will return in the future to this work, because in addition to its relationship with the real character of Ōuyáng Xún, the story reflects concepts related to Taoist internal alchemy (內丹 nèidān).

The first topic relates to the depictions of Hanuman in Southeast Asia as a promiscuous white monkey who likes to kidnap women. In Sìchuān a mythical narrative would develop in which the monkey would kidnap women to take them to his lair in the mountains, turning them into concubines, and would finally be killed by their husbands.

On the other hand, Èrláng was a hunting god worshipped in the West of Sìchuān, whose cult would spread throughout the region in the tenth century, and finally throughout the rest of China. Given his growing popularity, the exploits of other great hunters and archers such as Yǎng Yóujī were incorporated into his figure, including the defeat of the white monkey.

In addition, in Sìchuān there was a belief that dogs had the power to protect the deceased from evil forces such as the white monkey. And, in the Xī Yóu Jì, it is precisely Èrláng with his hunt who finally captures Sūn Wùkōng.

The god Èrláng with his dog hunting Wùkōng.

Buddhist allegories

In China, the introduction of Buddhism, which taught that all animals have souls, reinforced indigenous beliefs in the magical properties of animals and their involvement of vital energy (qì). With the translation of sutras into Chinese, the first allegories began to appear that compared the human mind to a restless monkey, seemingly uncontrollable. This point is important, because often the author of Journey to the West refers to Wùkōng as "Monkey-Mind" (心猿 Xīnyuán). Is Wùkōng really a representation of Xuánzàng's mind, indomitable at first, and subsequently disciplined until enlightenment is reached?

Fujian's monkey cult

At the end of the Táng dynasty, there existed in the region of Fújiàn 福建 a legend about a monkey that was captured and used as a mold for a clay sculpture in a temple, which was called "Monkey King". With his body encased in clay, his spirit began to torment the inhabitants of the region, causing disease and death, and causing the population to go mad. The temple where the statue was held in was filled with people who brought offerings to appease the spirit. Finally, an old man managed to free the spirit of the Monkey King by reciting the Mantra of Great Compassion (大悲咒 dà bēi zhòu).

The Kozanji text

The first written documents found that relate Xuánzàng to a monkey-disciple date from the Sòng 宋 dynasty, the most important of which is the so-called Kōzan-ji text 高山寺, which gets its name from the monastery where it was found, in Japan. In the stories told in this text, the monkey-disciple is the only pilgrim of the entire Xuánzàng's entourage who has a defined identity.

Along with this text, there are others on the south coast of China that also relate Xuánzàng to a monkey-disciple.

Sources contemporaneous with the Xi You Ji

During the Míng 明 dynasty, Zhèng Zhīzhēn 鄭之珍 wrote an opera called Mùlián jiù mǔ quànshàn xìwén 目连救母劝善戏文, based on the Buddhist folktale Mùlián jiù mǔ 目连救母 ("Mùlián Rescues His Mother"). This tale, whose earliest copy was found in the Mogao caves (莫高窟 Mògāo kū), in Dūnhuáng 敦煌, and based in turn on a Buddhist sutra of Indian origin, tells how Maudgalyayana (Mùlián) travels to hell to rescue his mother, who has been reborn there due to her karmic debt. This story would originate the Ghost Festival (鬼節 guǐjié).

In Zhèng Zhīzhēn's opera, Mùlián has a monkey-disciple referred to as Báiyuán (White Ape). In addition to keeping certain parallels with the story of the Ramayana, there are already similarities with the Xī Yóu Jì (the disciple-monkey is subdued by the generals of Heaven and ordered to help Mùlián by Guānyīn).

As Hera S. Walker proposes, the existence of indigenous legends of the white monkey in China would be the key factor that would make possible the assimilation of foreign elements from India and, in particular, from the Ramayana into the local culture. In this way, Wú Chéng'ēn 吳承恩, considered the author of Journey to the West, would have had at his disposal a long tradition of legends on which to base his novel and the character of Sūn Wùkōng.

Sources:

Hera S. Walker, Indigenous Or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Números 81-87; Sino-Platonic Papers n. 81 (Septiembre 1998).

Chen, Jue. “Revisiting the Yingshe Mode of Representation in ‘Supplement to Jiang Zong’s Biography of a White Ape.’” Oriens Extremus, vol. 44, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003, pp. 155–78.

THE EARLIEST PICTORIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF APE TALES An Interdisciplinary Study of Early Chinese Narrative Art and Literature* BY WU HUNG (Harvard University).