What can the seemingly antitetic arts of swordsmanship and calligraphy have in common? Let's explore the relationship between calligraphy and martial arts.

In Chinese culture, the concepts of Wǔ 武 and Wén 文, which represent the military and civil spheres in state government, are considered opposite but complementary: two sides of the same coin. At the individual level, these concepts find their best representation in two seemingly antithetical but very similar arts: swordsmanship (Dāo Fǎ 刀法) and calligraphy (Shū Fǎ 書法); the art of the sword and the art of the brush. Therefore, often the best swordsmen were also great calligraphers.

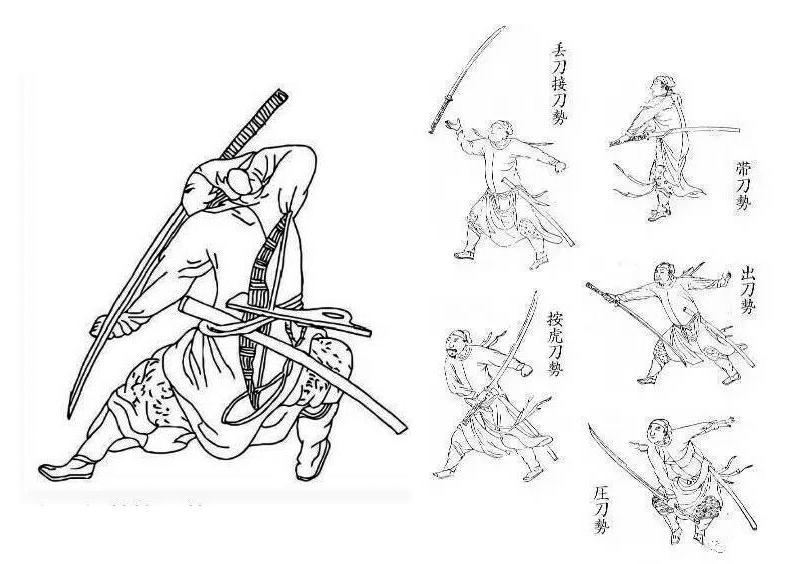

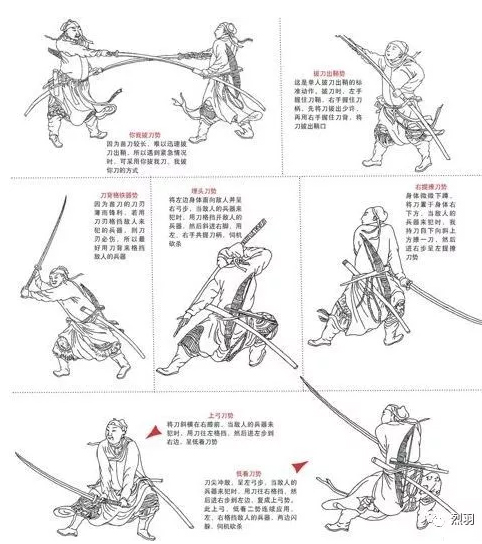

Illustrations of ancient sword manuals.

But what can these two artistic forms, whose goals are so distant from each other, have in common? The ultimate goal of martial arts is to defeat the enemy; that of calligraphy, convey a message in a plastic and aesthetic way. However, both are expressions of the mind that manifests itself in a body movement that tends to seek perfection.

To achieve this perfection one needs to develop calm and inner harmony. The necessary mental state is the same for both arts; it is imperative to adopt an attitude of detachment. This attitude is expressed in the Taoist concept of Wú Wéi 無為, sometimes translated as "non-action" or "effortless action". This concept should not be understood as the total absence of action, but rather as an action detached of the results it may produce: in this case, art should have no purpose other than art itself.

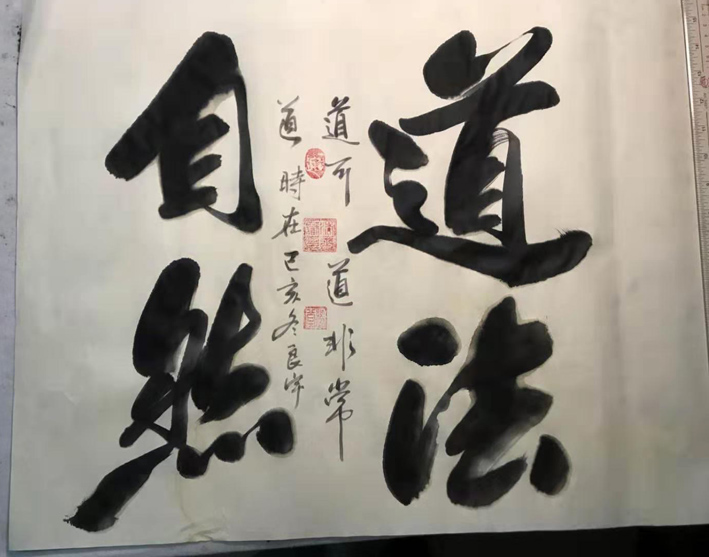

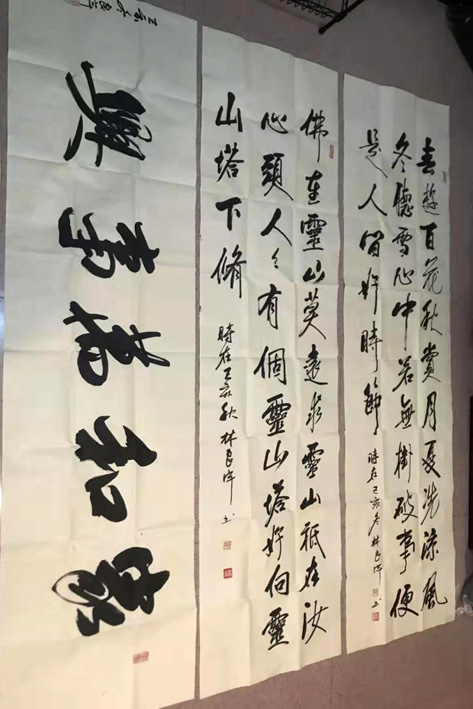

Master Lín Liáng Yǔ 林良宇 in Guǎngzhōu 广州 practicing calligraphy.

In practice, both calligraphy and martial arts need patience and perseverance. It is interesting to mention that, in Chinese martial arts, many techniques, both empty-handed and weapon techniques, are named after the basic strokes of the brush, such as piě 撇 or nà 捺. It is not enough to reach an intellectual understanding of how a movement should be executed; this movement has to be repeated hundreds of times until it is possible to observe an improvement in its execution. This requires constant daily practice. Through practice, the artist no longer thinks about how to execute the technique, but it becomes a natural and spontaneous way of moving.

When we talk about achieving "perfection", we mean a level of mastery in which there are no errors. Neither calligraphy nor combat allow mistakes; you can't correct what's already done. In a fight with weapons, an error probably means death, just as ink leaves an indelible print on the paper, and if there is a single mistake in a stroke, the entire roll must be discarded. Both movements, that of the brush and that of the sword, must therefore be executed perfectly. This perfection is achieved through repetition, by which the movement is "printed" in the muscle memory. By repeatedly performing the same movement, the unnatural becomes natural, and a gesture that previously seemed forced becomes fluid and instinctive.

In this quest for perfection emotions play a very important role. In calligraphy, emotions are laid bare, embodied directly on paper, and can no longer be concealed or hidden in any way. It is not allowed to touch up the lines once they are drawn. In both brush strokes and sword strokes, movements need smoothness, but at the same time energy. There should be neither tension nor flabbiness; in this way the movements will be fluid and energetic. To achieve this state one has to train his breathing and posture and, above all, his attention. The mind must be emptied of thoughts.

The ink on the paper is a reflection of one's mind. Likewise, the movements of the sword are reflections of one's mind. Any emotion that appears to cloud calm is perceived either on paper or in combat. There must be no doubt.

Calligraphy by Lín Liáng Yǔ 林良宇. Ink on paper is a reflection of one's mind.

Another important similarity between calligraphy and martial arts is rhythm. In calligraphy, strokes have to follow a certain order, and the brush must move smoothly between one stroke and the next, just as martial arts movements must be chained rhythmically and smoothly. If the attention drops, the rhythm breaks. Both arts are forms of meditation in motion, exercises of mantaining attention uninterruptedly. Although each movement requires a certain speed, neither the brush nor the sword can stop.

At the highest levels of practice, rules and technique must be forgotten. Basic strokes or strikes no longer exist; parts are integrated into the one. In combat, the joints move in a coordinated way like a single piece, it is the whole body as a whole that produces the movement: the pieces do not exist separately. Similarly, in calligraphy there are no longer strokes or characters, and only the movement of the brush exists.

The use of an external object is also common to calligraphy and weapon combat. One needs to concentrate mind and breath to bring qì 氣, the inner energy, to the tip of the object being handled. In this way, the object is no longer something alien to us, a prosthesis, but becomes an extension of one's body.

Dāo Fǎ 刀法 manuals.

All this has been called, in terms of modern psychology, to keep the mind in a "state of flux". This state of flux does not consist of wandering the mind from one place to another, but of the latter not stopping at a particular place, not sticking to any idea. Thoughts come in, but we let them go without grabbing them. Although the concept is the same, we prefer to call it "empty", "emptiness". When the mind stops at an idea, all the others cease to exist. The void, on the other hand, is fertile, it is the fullness of possibilities. In combat, if the mind stops for a single moment in a movement, in a particular technique, the others are no longer possible and the combatant will not be able to react spontaneously to the attack of his opponent. The same is true when the brush stops at the paper. Sword and brush must be the subconscious mind itself.