Introduction

Wén 文 and wǔ 武 are, in Chinese philosophy and thought, a pair of dichotomous and complementary concepts, which refer to the civil and military spheres of culture and politics, respectively.

Meaning of wen and wu

Wén is sometimes translated as culture and, indeed, this is one of its meanings. However, when we talk about the wén-wǔ pair, it does not seem right to us to speak of wén as a culture since, from an anthropological perspective, culture is a much broader field than that referred to here by wén. In fact, martial or military aspects, such as the art of warfare, martial arts styles, weapons production, punishments of criminals, etc., are part of and integrated into the culture. Therefore, when we speak at the macroscopic or state level, wǔ refers to the military and the use of punitive force (such as the sentencing of criminals) and wén to the civilian sphere of government. And when we speak at the microscopic or individual level, wǔ refers to martial training and wén to literary/artistic education, which encompasses philosophy, literature, poetry, music, etc.

It is important to note that, in ancient China, the military refers to all those activities or methods aimed at stopping or punishing injustices, rebellions or invasions. Thus, war, in its broadest sense, encompassed both military and political and diplomatic actions aimed at preventing conflicts. Consequently, wǔ includes activities that make use of physical force, coercion and punishment, as well as tricks that could be considered immoral because they are based on deception. In this way, both the criminal law, as well as the physical and sports activities, which were intended to prepare the body and mind for fighting, belong to wǔ. Even board games based on principles of military strategy, such as xiàngqí 象棋, related to chess, belong to this category.

The principles of wén and wǔ are stereotypes, which since ancient times have been used to classify, organize and interpret both social and political aspects and structures.

Origin and development of the wen-wu dichotomy

Shāng 商 dynasty is the first Chinese dynasty for which there is historical evidence. Its reign was marked by military conquests and territorial expansion.

At the end of the dynasty, in the face of population growth and increased internal tensions, people realized that war, while conducive to territorial expansion and cultural enrichment, should be accompanied by internal order and social stability. Since this time the relationship between wén and wǔ has been characterized by tension or conflict, and states have tried to resolve this tension by seeking a balance between these two principles.

It is not clear at what point in China's history these two concepts, no doubt already existing previously, began to be related as dichotomous and complementary pairs, but their relationship is already guessed in the figures of the founding kings of the Zhōu 周 dynasty, known posthumously as Kings Wén 文 and Wǔ 武.

Kings Wen 文 and Wu 武

Jī Chāng 姬昌 had held the office of Count of Zhōu 周 during the Shāng 商 dynasty.

Faced with the inability of the last Shāng rulers, the Count of Zhōu proclaimed to have received the Mandate of Heaven (天命 tiānmìng) to overthrow the Shāng and establish a new dynasty. Although it was his son Jī Fā 姬發 who, four years after his death, finally completed the conquest of the Shāng state, Jī Chāng was posthumously appointed king under the name of King Wén 文王 and considered the founder of the new Zhōu dynasty.

Jī Fā, the first Zhōu emperor, in turn received the posthumous name of King Wǔ 武王.

Despite their military conquest over the Shāng dynasty, kings Wén and Wǔ were concerned with legitimizing their aspirations to the throne and their rule by maintaining virtue (德 dé). They were the first rulers to resort to the concept of tiānmìng or the Mandate of Heaven. According to this idea, the right to rule over the Chinese empire was granted by Heaven to a sovereign or dynasty based on the virtue of their rule. In this way, a ruler, if not guided by the principles of virtue and righteousness, could lose the right granted by Heaven, which would transfer its mandate to a new emperor. This appeal thus justified the usurpation of the throne by the Zhōu.

However, the new rulers, aware that virtue alone was not enough to hold the conquered empire together, relied on a system of punishments to maintain order. In this way, the idea developed that a balance between wén and wǔ was fundamental to governing the empire. Wǔ would thus be conceived as the tool of change when virtue in government has been lost, but this tool would be relegated to the background once it has served its purpose, allowing it to manifest itself in all its glory to provide social welfare to the subjects of the empire.

Despite their posthumous names, we are not to see in kings Wǔ and Wén the antithesis of each other, pure embodiment of the wǔ and wén principles, but both represented the synthesis of those values.

Two centuries later, at the end of the Western Zhōu dynasty, the complementarity of wén and wǔ was already part of political ideology. However, until this time, there was no separation in government between civil and military affairs, and both were in charge of the same single person.

In the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代 Chūn-Qiū Shídài, 771-476 a.C.), the concepts of wén and wǔ began to acquire their abstract meaning as principles of government, and their association with the philosophical principles yīn-yáng 陰陽 occurred. It was from this time that the wén- wǔ division in the state apparatus arose, which would eventually lead to a specialization of official positions according to these categories. As the military was understood in a broad sense of maintaining justice, thus wǔ was conceived as a way to maintain and protect the civil sphere, wén.

The character wǔ 武, the martial.

Wen and wu in the state government

Different schools of thought have had different views on the relative importance of wén and wǔ.

Most Confucian thinkers subordinated wǔ to wén. Although they understood the military as something necessary, they relegated it to a secondary plane. Some of them went so far as to reject wǔ altogether, denying its importance. Although Confucius himself encouraged his students to practice archery and chariot racing, activities belonging to wǔ, we must bear in mind that these sport activities were typical of the aristocracy.

For Confucius, in the practice of archery ritual execution and marksmanship weighed more than the ability to pierce the target, that is, he attached greater importance to form than to function. In order to pierce the objective, great physical strength was necessary when it came to drawing the bow, a strength possessed by the war archer but not by the cultured man belonging to the civil elite. By divorcing the archery of competition from the ability to pierce the target, Confucius made competition accessible to the civil aristocracy, belonging to the sphere of wén, in addition to the military class, and made the Confucian scholars not look bad in front of uncultivated warriors.

On the other hand, some thinkers of the legalistic school of thought went to the opposite extreme, considering wǔ as the main factor in the maintenance of the state.

Sūn Zǐ 孫子, in his famous military treatise "Master Sūn's Principles of War" (孫子兵法 Sūn Zǐ Bīng Fǎ)*, states that "it is necessary to inspire soldiers by means of wén, and subdue them by wǔ":

故令之以文,齐之以武

gù líng zhī yǐ wén, qí zhī yǐ wǔ

We can understand this phrase as "treating soldiers with humanity but controlling them through military discipline."

In the Wú Zǐ Bīng Fǎ 吳子兵法 (Principles of War of Master Wú), another important military treatise, it is read that "the commander of an army is one in whom the civilian (wén) and martial (wǔ) elements are combined".

These texts, dating from the fifth and sixth centuries a.C., as well as other texts of the time, show that by then the concepts of wǔ and wén were already linked as an organic unit.

Later, in the Hàn 漢 dynasty, wǔ also underwent a process of mythification: Heaven (天 Tiān) would have bestowed the first weapons on Huángdì 黃帝, the Yellow Emperor, to whom he also transmitted the principles of the war.

This process would culminate in the Táng 唐 dynasty with the cult of wǔ and the appearance of the so-called wǔ miào 武庙 or Martial Temples. In these temples tribute would be paid to several military figures, which initially numbered eleven, the most important of which was the military strategist Jiāng Zǐyá 姜子牙, who helped kings Wén and Wǔ overthrow the Shāng and establish the Zhōu dynasty. Throughout history, these figures changed, until in the Qīng 清 dynasty the main place of the martial pantheon was occupied by Guān Yǔ 關羽, the famous general of the Three Kingdoms (三國 Sān Guó), who would be known as Guān Dì 關帝.

Statue of Guān Dì 關帝.

In the Qīng era, Manchu rulers attempted to gain the approval of members of the Hàn elite, showing themselves to be competent in both spheres, wén and wǔ. For better or worse, China, throughout its history, has always sought to show itself as a morally and culturally superior nation. That is why the balance of wén and wǔ in the exercise of power became key to justifying the right to reign.

Wen and wu at the individual level

Despite seeking this balance between wén and wǔ in government, the process of specialization did not offer the same prestige to scholars and military men. Although the latter undoubtedly had a great deal of power, they were often sconed by the literati, and belonged to a lower social category.

In turn, women were excluded from all this categorization. Wén and wǔ were always a man's thing. Although there were women warriors, empresses, poetesses, etc., these were always the exception to the rule. When women practiced some kind of martial exercise, or showed a fondness for literature, this remained in the private sphere and was in no way publicly acknowledged. Even in certain arts, such as calligraphy, a woman was considered to lack the inner energy necessary to capture the essence of art. Wén and wǔ were related to masculinity.

The ideal of masculinity, although not stable over time, used to attach greater importance to the qualities associated with wén. Education, knowledge and etiquette outweighed strength or violence in defining masculinity. Therefore, that of the literati was the predominant model of masculinity over time.

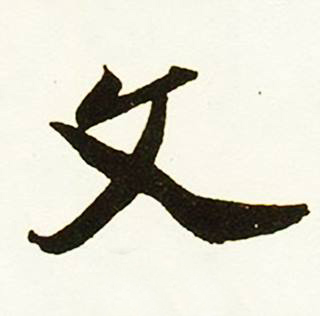

Character wén 文, the civil.

There are also differences between wǔ and wén men in their relationship with women. While civilian officers were to fulfill their obligations to the opposite sex, the martial man expressed his masculinity by resisting female charms and his own impulses and desires.

However, above the "pure" types of wén and wǔ were those that combined both aspects. This is evident in the heroes of classic Chinese novels, whose most outstanding characters are those in which both principles are in balance.

Today, these classic models are changing due to globalization and the introduction of Western models through cinema and intercultural contact.

Conclusion

The wén-wǔ polarity can be understood, at the organizational level of the state government, as specialization in civil and military affairs respectively; and at the level of the individual, such as the development of literary and martial qualities or skills.

In both cases, wén has enjoyed, throughout Chinese history, a certain predilection in society over his complementary opposite, wǔ. However, with a few exceptions, a balance has always been sought between the two spheres, with the combination of these two principles understood as superior to the development of only one of them.

Notes:

* Sūn Zǐ 孫子 is best known for the Wade-Giles romanization: Sun Tzu. The title of his work, Methods or Principles of War is usually translated as "The Art of War".

Sources:

- Gawlikowski, Krzysztof. “THE ORIGINS OF THE MARTIAL PRINCIPLE (WU) CONCEPT.” Cina, no. 21, 1988, pp. 105–122.

- Military Thpught in Early China, Christopher C. Rand. SUNY Press, 2017.

- Chinese Masculinity: Theorizing Wen and Wu. Kam Louie and Louise Edwards, published in East Asian History nº 8, december 1994.