Introduction

Habits in tea consumption have changed a lot throughout history. Currently, tea is consumed as an infusion, submerging the whole leaf in hot water, and then removing it, drinking only the resulting liquid.

But this method has been used only since Míng 明 dynasty. Until then, the preparation of tea went through several very interesting stages, which gave rise to the expression "eating tea". To understand how we have come to the current form of consumption, let's review the methods of tea preparation during Táng 唐 and Sòng 宋 dynasties.

Táng dynasty: “boiled tea”

During Táng dynasty (618-907), the method by which tea was prepared is known as jiān chá 煎茶 (boiled or cooked tea, in decoction).

From a cake of pressed tea leaves (茶餅 chá bǐng), a piece was taken, toasted and ground into powder, using a specific instrument for such use. Once ground, the powder was screened and boiled. When it reached the desired degree of boiling, the concoction was served with a spoon into a bowl, and seasoned with salt, ginger and other ingredients, thus being ready to drink.

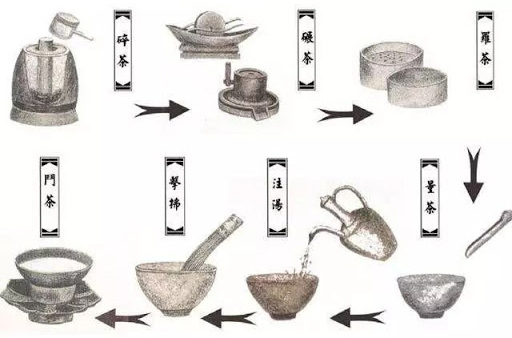

Grinding of tea.

The result was a thick concoction containing the ground tea leaf, which would be ingested with the rest of the ingredients. That is why the term "eating tea" (吃茶 chī chá) was used to refer to its consumption. In classic Chinese books, such as The Water Margin (水滸傳 Shuǐ Hǔ Chuán) or Dream in the Red Pavilion (紅樓夢 Hóng Lóu Mèng), this expression of "eating tea" appears often.

Sòng Dynasty: “whisked tea”

During Sòng Dynasty (960-1279) there was a major change in the way tea was prepared. All the seasonings that were added in Táng dynasty's jiān chá ceased to be used, and a taste for pure tea was developed. However, the preparation method had not yet reached its current form.

As in Táng, the tea leaf was ground to dust. However, this powder was no longer boiled inside the pot, as before, but the water was heated separately and then poured over the tea, similar to how it is made today. Nevertheless, the powdered leaf was still ingested with the liquid, so it remained a way of "eating tea".

The amount of tea and water was adjusted according to the size of the cup, and the water was gradually poured, while the mixture was beaten with a bamboo whisk. The result was a frothy, whitish "soup". This way of making tea was known as diǎn chá 点茶 ("whisked tea"), similar to the current way of drinking Japanese matcha 抹茶.

Process of preparing diǎn chá 点茶, "whisked tea".

The colour of the concoction was an important aspect in the result, with pure white being appreciated above the rest, followed by "emerald white". So much so that it was written that

茶与墨正相反,茶欲白,墨欲黑

chá yǔ mò zhèng xiāng fǎn , chá yù bái , mò yù hēi

tea is opposite to ink, good tea is white, good ink is black

(侯鯖錄 Hóuqīng lù, “Records of Hóuqīng”)

In addition, the famous poet of the Sòng dynasty, Sū Dōngpō 蘇東坡, wrote:

雪沫乳花浮午盞

xuě mò rǔ huā fú wǔ zhǎn

snow foam and milk flowers floating in a cup at noon

to refer to diǎn chá.

In the preparation of diǎn chá, the boiling degree of water was especially important; it was to reach a specific point, called hòu tāng 候湯. If the water temperature did not reach this degree, too much foam was created, and if it boiled for longer, the tea would sink to the bottom of the cup. Therefore, it was necessary a great skill to boil the water to the right point, to maximize the aroma, taste and color of the tea.

Due to the difficulty of discerning the degree of boiling of the water by sight, it was heated in a wide-based, narrow-necked high jug, in which the correct point could be distinguished by the sound that water makes when boiling.

Luó Dàjīng 羅大經 (1195–1252), a scholar of the Sòng dynasty, defined three degrees of boiling by distinguishing the characteristic sound of each. According to him, the first boil is like the singing of insects and cicadas; the second boil is like the sound of a thousand carts arriving; the third boil is like the sound of the breeze melting with that of mountain streams. It is this third boil (三沸 sān fèi) the ideal one for the preparation of tea.

In order to highlight the white colour of the tea, it was prepared in small bright black ceramic cups or bowls. This pottery is still produced today and is known as jiànzhǎn 建盞 (Jiàn cups, because they are produced in the Jiànyáng 建陽 region, in Fújiàn 福建), and is characterized by its patterns that resemble "jade-colored rabbit hair". The cups had to be deep and wide to allow the foam to be whisked well. This material has a slow conductivity of heat, so it preserves temperature especially well.

Jiànzhǎn 建盞 ceramic cups, with jade green "rabbit hair" pattern.

Wú Zìmù 吳自牧, an author from the Sòng dynasty, mentioned diǎn chá among the "Four Arts of Life" (生活四藝 shēng huó sì yì), which at the time were called "Four Types of Trivialities" (四般閑事 sì bān xián shì). The other three were: burning incense, floral arrangements and the arrangement of paintings. Among the four, he mentioned diǎn chá as the most common, vivid and refined of the pleasures of life.

During this period, so-called "tea contests" (斗茶 dǒu chá) emerged among upper classes, as a form of entertainment. In these, diǎn chá was prepared, and participants had to guess the origin of the tea, the harvesting season, as well as the quality of the water. Dǒu chá was introduced to Japan by Japanese monks, where it developed independently.

Míng dynasty: tea in infusion

Zhū Yuánzhāng 朱元璋 (Hóngwǔ 洪武) was the first emperor of the Míng dynasty. The seventeenth of his sons, Zhū Quán 朱權, disagreeing on political affairs with his older brother Zhū Dì 朱棣, who would succeed his father reigning under the name of Yǒnglè 永樂, withdrew from worldly life taking refuge in Shēnshān 深山.

Zhū Quán 朱權.

Emperor Hóngwǔ, who came from a poor family and knew the difficulties of the peasants' lives, abolished the production of tea bricks and cakes, in order to free farmers from the difficulties of this arduous production process, replacing it with the production of loose-leaf tea.

In his retreat in Shēnshān, Zhū Quán developed a new method of preparing tea, known as yuè yǐn 瀹飲 (which we can translate as "drinking in infusion"). This method separated the tea leaves from the liquid resulting from the brew, drinking only the latter.

Thus, in the 24th year of his father's reign, Zhū Quán published a book called Tea Manual (茶譜 Chá Pǔ), in which he echoed the imperial slogan of fèi tuán gǎi sàn 廢團改散 (literally, "abandon the grouped, replace with the scattered"). Tuán 團 ("grouping" or "group") referred to the forms of pressed tea known as túochá 沱茶; 散 ("dispersed") referred to loose-leaf tea (sàn chá 散茶).

Old blocks of tea pressed and packed in bamboo.

Zhū Quán's method of brewing tea has since been adopted and has become the most common method of consuming tea worldwide. Six hundred years later, this form of preparation seems to us to be the most natural and yet, if we look back, we realize that it is not at all and, moreover, it is by no means the only way to make tea.