Introduction:

This post is a continuation of The Afterlife in Chinese Culture (I): The Realm of the Dead.

In the previous article we introduced concepts such as spirit or ghost (guǐ鬼), "world of darkness" (yīnjiān 陰間), Dìyù 地獄, etc., and saw the most relevant features of the Chinese conception of the world of the dead. We recommend reading it to better understand this article.

Next we will try to explain how is the journey that the soul of the deceased makes after death and his passage through the Ten Courts of the Underworld (十殿閻羅 shí diàn Yánluó), and we will explain how this idea was formed progressively throughout the history of China.

The journey after death:

According to popular beliefs of the Chinese people, after death, the tutelary deity of the locality (土地神 Tǔdìshén) claims the spirit of the deceased and takes it to the underworld, crossing the so-called Ghost Gate or Spirit Gate (鬼門關 guǐ mén guān).

Here, the gatekeepers demand that the soul of the deceased show a pass, without which it is not allowed access to the underworld. This pass is a piece of yellow paper that is burned as part of the mortuary rites of the deceased, to accompany the soul in the afterlife. That is why souls who had a violent death and whose descendants have not been able to fulfill the rites, cannot access the underworld and remain tied to the world of the living1.

Among these guardians are the pair of deities known as Hēibái Wúcháng 黑白無常 ("Black and White Impermanence"), which according to some narratives perform the function of transferring the soul to the underworld. Sometimes these deities are held as one, called Wúcháng guǐ 無常鬼, Ghost or Spirit of Impermanence.

Hēibái Wúcháng 黑白無常 ("Black and White Impermanence")

After passing the Spirit Gate, the soul travels along the so-called Yellow Springs Road (黄泉路 Huángquán lù)2, after which the deceased arrives before the city god (城隍神 Chénghuángshén), a local spirit in charge of protecting the town or village and its corresponding location in the world from the dead.

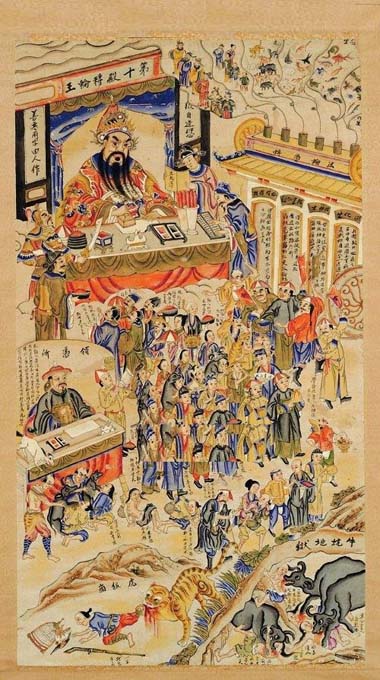

This deity keeps the record of the good or bad deeds performed in life by the deceased, and presents the soul before the first of the Ten Magistrates of King Yánluó (十殿閻羅 shí diàn Yánluó).

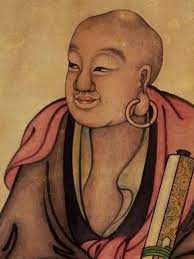

These magistrates, also known as Ten Kings (十王 shí wáng) of the Underworld, will be in charge of judging the actions of the deceased and applying the corresponding punishments. Virtually all souls are accountable to these courts. Only in exceptional cases of virtue is the deceased allowed to pass directly to the Pure Land of the West (Xīfāng Jí Lètǔ 西方極樂土 or Jìngtǔ 淨土) of Amitabha Buddha (Āmítuófó 阿彌陀佛), or to Heaven (Tiān 天), ruled by the Jade Emperor (Yù Dì 玉帝).

Amitabha Buddha (Āmítuófó 阿彌陀佛) and the Pure Land of the West (Xīfāng Jí Lètǔ 西方極樂土).

The soul that is judged will spend seven days in each of the first seven courts, yielding a total of forty-nine days. It is worth mentioning King Yánluó3 閻羅王, the fifth of the tribunals, and King Tàishān 泰山王, the seventh, on whom we will return later.

King Tàishān 泰山王.

Among the guardians who assist King Yánluó are the well-known Niútóu 牛頭, "Ox-head", and Mǎmiàn 馬面, "Horse-Face", who are in charge of escorting the souls on their way to his trial.

Mǎmiàn 馬面 and Niútóu 牛頭.

The deceased shall be judged in the eighth court on the hundredth day after death; in the ninth court, after one year; and finally in the tenth court three years after death. Coinciding with these dates, the living descendants of the deceased must fulfill certain commemorative rites and make offerings for the purpose of alleviating the suffering of the dead.

After the last trial in the tenth court, the soul is released and reincarnated into one of the six realms of existence (liùdào 六道), according to his karma. In the world of the living, funeral rites and mourning are intended to alleviate the transit of the deceased through the ten courts.

Above even the ten kings is the figure of the bodhisattva Dìzàng 地藏 who, in addition to instructing sentient beings of the six realms of existence, made the vow not to attain Buddhahood until all hells were emptied of souls.

Bodhisattva Dìzàng 地藏.

This process is described in Buddhist and Taoist scriptures, such as the Scripture of the Ten Kings (十王經 Shí Wáng Jīng) and the Jade Record (玉歷寶鈔 Yùlì Bǎochāo), but, in the popular imagination, souls remain in the world of the dead after the last judgment for quite some time before reincarnating, leading an everyday existence like the one they had on earth. This time varies from a few years to as many as those the deceased has lived on earth.

During this period of permanence in the yīn world (yīnjiān 陰間), communication between ancestor and descendants is possible, and the former must cover a series of needs, such as clothing, money, etc., which are satisfied by offerings that the descendants make by burning paper objects.

Before being reincarnated, souls must still cross the so-called River of Oblivion (忘川 Wàng chuān), where the last ordeal awaits them. But this part we will see in a next post. Now let's examine how the idea of the Ten Kings developed.

Origin of the Ten Kings

The Ten Courts of the Underworld originate around the ninth century as a crystallization of a series of ideas that appear before gradually. Let's try to outline the progression that concluded with this worldview of the dead.

Pre-Buddhist era

Before the Hàn 漢 dynasty (202 BC-220 AD), descriptions of the world of the dead are blurry and simple, without providing a detailed view of the underworld. It is associated with cold and darkness, both yīn attributes, but there is no mention of the punishment of souls.

From the Hàn dynasty onwards, tombs begin to be built as an imitation of houses, reflecting a change in the perception of the yīn world, which begins to be understood as similar to the world of the living.

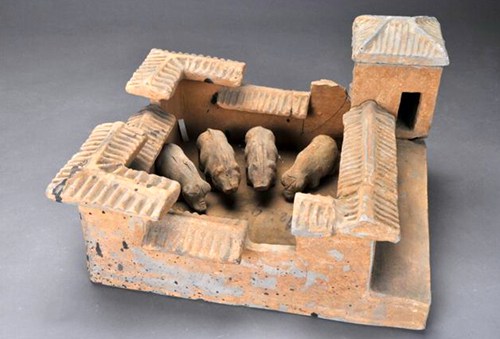

Funerary objects, which were once real everyday objects and included the possessions of the deceased, begin to be replaced by miniature representations made of clay (明器 míngqì), manufactured specifically for this use.

Funerary objects known as míngqì 明器.

Later, with the invention of paper, these funerary objects began to be manufactured as figures with the new material.

During Hàn, the concept of post-mortem retribution or punishment did not yet exist. The imitation of the world of the living by the lower world extended to the administrative system: the same bureaucracy that existed at that time in the Hàn empire was implemented in the yīn world. The same administrative procedures were required in the kingdom of the dead, from buying a home to accessing a job or paying taxes. The offerings made by the living to their ancestors were therefore intended to alleviate these worldly needs of their ancestors.

In the tombs, in addition to the objects of daily use of the deceased or their representations, inventories of these articles were included, and other documents addressed to the authorities of the underworld, so that they could adequately record the admission of the dead as well as all their possessions.

In the fourth century, the Sōushénjì 搜神記, an anthology of supernatural or paranormal stories attributed to Gān Bǎo 干寶, records the first accounts of travels in the netherworld. These stories tell of cases of dead people coming back to life.

These cases were usually due to bureaucratic errors, from which the world of the dead, as a faithful reproduction of that of the living, was not exempt either. Among these accounts are cases of people who were summoned to the underworld by mistake (for example, before two people of the same name, the local tutelary deity claims the soul of the one who must not die yet). Realizing the error, the authorities of the afterlife had to send the soul of the deceased back to its body, which could lead to other problems, if the body had already been buried.

In these tales there are still no Buddhist or Taoist influences perceived, nor is there punishment in the afterlife.

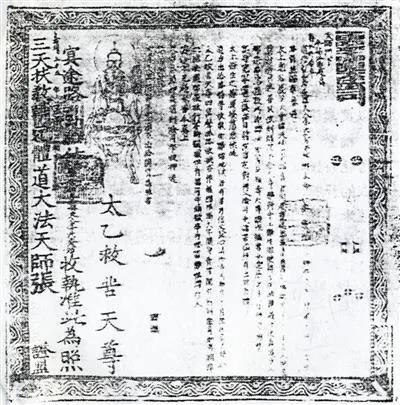

After Hàn, the earthly administrative system had continued to evolve, and so did the administration of the underworld. In the seventh century, among the documents that accompanied the deceased there was one called míngtú lùyǐn 冥途路引, "travel permit to the underworld", which facilitated access to the netherworld and was issued by Buddhist or Taoist authorities. This document is still used today in some regions of China.

Travel permit to the underworld (míngtú lùyǐn 冥途路引).

From the Three Kings to the Ten Kings

The Ten Kings or Ten Courts of the Underworld originated from Buddhist influences that were combined with the implementation of the administrative system of the Táng 唐 Dynasty (618-907) in the bureaucracy of the world of the dead.

In the Míngbàojì 冥報記 (Register of Retributions in the Underworld), a text from the early seventh century in which karmic retribution is indoctrinated, the rule of the underworld falls on three kings: King Yánluó, King Tàishān and King Zhuǎnlún 轉輪王 (Wǔdào Zhuǎnlún Wáng 五道轉輪王, "King Who Turns the Wheel of five Paths"). While Yánluó and Zhuǎnlún kings come from Indian Buddhism, King Tàishān is of genuinely Chinese origin.

King Yánluó 閻羅.

This three-king system seems to have its origin in the centuries before the establishment of the Táng dynasty, but evolved to adapt to changes in state organization during this dynasty. During Suí 隋 and Táng a system of government of "three departments and six ministries" (三省六部制 sān shěng liù bù zhì) was established, and the Three Kings went on to perform functions associated with these three departments.

During Táng, a new figure was introduced into the administration of the underworld: the bodhisattva Dìzàng. In the Dìzàng Púsà Jīng 地藏菩薩經 (Sutra of Bodhisattva Dìzàng), an apocryphal text from mid-Táng, four reasons are explained why Dìzàng assumes a position in the underworld: first, for fear that king Yánluó's judgments will be unreliable; second, for fear that written documents would be confused; third, out of concern for those who died before their time came; and fourth, to help souls who had already received their punishments to leave the underworld. Subsequently, the authority of this character was increased to the point of supervising trials.

Over time, this system of Three Kings expanded to ten, with Yánluó, Tàishān and Zhuǎnlún occupying the fifth, seventh and tenth places, respectively. Although the cult of King Yama (Yánluó) is of Indian origin, this system of various kings is a Chinese creation.

King Zhuǎnlún 轉輪王.

The first text to mention the Ten Kings by name is the Scripture of the Ten Kings (十王經 Shí Wáng Jīng), which probably dates from the ninth century. In this text, the underworld finally takes its full form. This model is a synthesis between indigenous Chinese ideas and those from India.

The number forty-nine, or seven times seven, is a number of special significance in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. According to the Tibetan Book of the Dead (Bardo Thodol), forty-nine are the days it takes for the soul to reincarnate. This number is the same that the soul passes in the first seven courts of the Chinese worldview.

However, as we have already mentioned, the last trial does not occur until three years after death. This satisfies the Confucian requirement to mourn the deceased for three years, although in popular belief the soul remains much longer in the yīn world.

As we can see, Buddhist beliefs have not replaced previous indigenous beliefs about the world of the dead, but are an addition. This paradigm thus represents a compromise between the beliefs of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.

The Taoist religion would also form in the twelfth century its group of kings based on the structure of the ten courts.

Mùlián Rescues his Mother

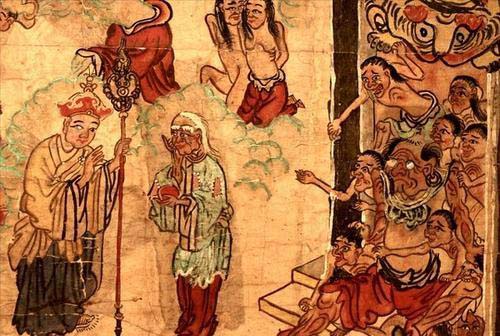

The world of the dead and the six realms of Buddhist existence are finally described with terrible clarity in a ninth-century text, Mùlián Rescues His Mother (目連救母 Mùlián jiù mǔ).

Although this story, in its most developed version, comes from a ninth-century manuscript found in Dūnhuáng 敦煌, it actually took shape progressively from much earlier.

Mùlián Rescues his Mother (目連救母 Mùlián jiù mǔ).

The first mention of Mùlián in a Chinese text appears at the end of the fourth century and, in the sixth century, the Yúlánpén sutra (盂蘭盆經 Yúlánpén Jīng) records his story. The story of Mùlián was progressively elaborated until culminating in the manuscript of Dūnhuáng.

The name Mùlián 目連 is an abbreviation of Móhē Mùjiànlián 摩訶目犍連, from the Sanskrit Mahā Moggallāna, who was one of The Buddha's main disciples and preceptor of his son Rahula. According to Indian Buddhist tradition, Moggallāna developed supernatural powers, being the only person whom the Buddha allowed to use such powers, due to his great righteousness and virtuous conduct.

Mùlián's mother, because of her many sins, had been reborn among the hungry ghosts4, one of the six kingdoms of Buddhist existence, characterized by incessant suffering.

Mùlián, after several attempts to bring his mother out of that existence, asks the Buddha for help, who instructs him to make offerings to monks and monasteries on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month, which would redeem seven generations of his ancestors. It is said that this resulted in the celebration of the Ghost Festival (鬼節 guǐ jié) on the same date.

Mùlián 目連.

The story of Mùlián Rescues his Mother offers one of the first representations of the underworld and the six kingdoms of existence, and would serve to spread this vision of the afterlife. Later it would be transformed into an opera that has been very popular for a thousand years.

Emperor Taizong's Journey to the Underworld

After the appearance of these texts of Buddhist origin with the description of the Ten Kings and the tortures of the underworld, the vision of the realm of the dead ceases to be peaceful and quotidian. These descriptions have since appeared in paintings and stories, where the Ten Kings were increasingly depicted similarly to government magistrates.

Worth mentioning is the story the journey to the underworldof of Emperor Tàizōng 太宗 of Táng, which appears in fragments of Records of the Court and the People (朝野僉載 Cháoyě Qiānzài), attributed to Zhāng Zhuó 張鷟 (660-740).

This text only mentions the emperor's visit to the underworld, without offering a detailed vision, which would be developed in later texts. The classic Chinese novel Journey to the West (Xīyóuiì 西遊記) offers an elaborate narrative about this myth.

Tàizōng's Journey to the Underworld in Journey to the West

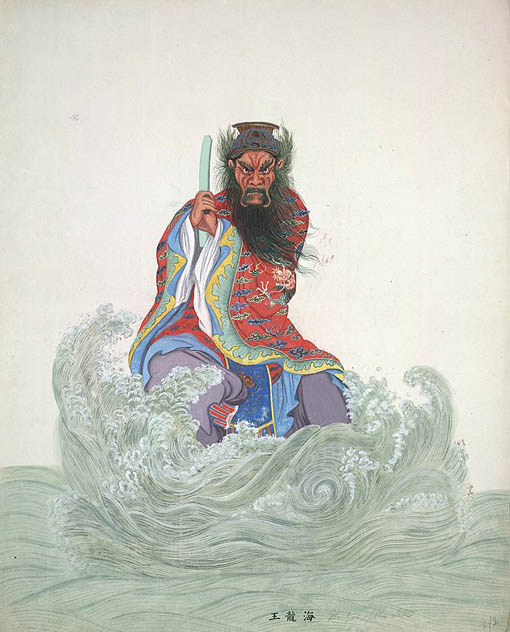

In Journey to the West we find an account of Emperor Tàizōng's journey to the underworld. In this story, one of the monarch's ministers had beheaded the Dragon King (龍王 Lóngwáng) of the Jīng River 涇河, even though the sovereign had promised to spare his life.

The Dragon King had committed capital offenses and had been sentenced to death by a judge of the human world, but he presented himself to the emperor in a dream begging for mercy, and the monarch promised to take care of the matter. On the night the execution was scheduled, the emperor invited the judge to play Chinese chess with the intention of holding him in the palace. But the judge, despite sleeping in the palace, executed the Dragon King in his dream.

Dragon King (龍王 Lóngwáng).

The Dragon King, from the world of the dead, accused the emperor of having failed in his word, having obtained death himself because of it. Tàizōng began to suffer from nightmares where he saw ghosts, fell ill and died. Just before his death, one of his ministers handed him a letter to a late friend of his, Cuī Jué 崔瑴, who had served the previous emperor, Tàizōng's father. He took the letter with him to the underworld.

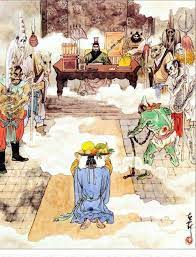

On the way to the underworld, Cuī Jué went out to receive the late emperor, who handed him the letter. In it, Cuī, who was now a magistrate in the Region of Darkness, was asked to intercede for the emperor.

After crossing the Ghost Gate (鬼門關 guǐ mén guān), the emperor meets his two deceased brothers, whom he himself had killed. They begin to beat him crying out for revenge until a guardian spirit separates them.

When Tàizōng, led by Cuī Jué, arrives before the courts of the underworld, the Ten Kings bow to him, as befits before the Son of Heaven (天子 Tiānzǐ). Then, everyone sits following the etiquette as hosts and guest.

The Ten Kings apologized to the monarch, saying that they knew the Dragon King was guilty but had been forced by protocol to summon the emperor. Then, they sent Judge Cuī for the records where the years of life of each person were specified. Cuī Jué, seeing that in the book it was written that the sovereign should die that same year, the thirteenth of his reign, modified the number thirteen changing it to thirty-three, thus extending Tàizōng's life span by twenty years.

Seeing the book with the modified number, the Ten Kings ordered Tàizōng's return to the world of the living. In gratitude, he promised to send them "southern melons" (南瓜 nánguā, that is, pumpkins), something they were lacking in the underworld.

As one only could leave the world of the dead through the cycle of transmigration, Tàizōng, accompanied by Cuī, had to go through hell before he could return. What he saw in hell horrified him.

Later, crossing the bridge over the Nàihé5 奈何 River, they reached a city where they found unattended ghosts whose cries begging for salvation moved Tàizōng, who promised to make offerings to these beings once he was back to life.

After a long journey, they reached the junction of the Six Paths of Transmigration, where the six realms of existence converge. Tàizōng returned to the world of the living and made sure to tell what he had seen, so that his subjects would cultivate virtue and follow the Buddha's law.

According to oral tradition, the offerings that Tàizōng made on his return from the underworld would have been the origin of the custom of burning paper objects as an offering to the dead. Historical records show that by the same time paper money offerings (紙錢 zhǐ qián) were already being made. This "spiritual money" that was burned began as an imitation of metals and silk made of paper, before paper money was invented in the ninth century.

In the twelfth century, paper sculptures as an offering of all kinds (houses, money, horses) was already common. These offerings were intended to ensure the deceased a stay as pleasant as possible in the underworld, and to allow him or her to enjoy the same comforts enjoyed by the living.

The exoticism of the Buddhist construction of the underworld disappeared over time, and the Chinese people ended up becoming familiar with that description. The various punishments inflicted by the acolytes of the ten kings were well known in the late imperial era, and the temples of the tutelary deity of the locality housed graphic representations of the underworld, as well as of the heinous punishments that were applied.

Notes:

1. We will return to this point in detail in the following article, which will deal with premature death or "death in vain" (枉死 wǎng sǐ).

2. Huángquán 黄泉 or "Yellow Springs" is another name for the world of the dead.

3. Yánluó is the abbreviation of the transliteration of Yamarāja (Yánmó Luóshè 閻魔羅社), the deity of death of the Indian Buddhist tradition.

4. Some narratives tell us that Mùlián's mother was reborn in hell, rather than among the hungry ghosts.

5. We will return to this part of the underworld in a future article.