This article is a continuation of History of Tea and its Culture (II): Táng Dynasty.

Tea culture during the Sòng

During the Sòng 宋 dynasty (960-1279), tea preparation reached its peak sophistication. Its consumption was already so ingrained among the population that the poet and scholar Wú Zìmù 吳自牧 considered it one of the seven essential daily products for any household, the other six being firewood, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce and vinegar.

The predominant way of preparing tea during this time is known as diǎnchá 點茶, which we can translate as "whisked tea" (whose preparation process we describe below), although of course other methods continued to be used to a lesser extent.

Diǎnchá already existed in Táng 唐, but the development during Sòng of better instruments for grinding tea encouraged the general predilection for this method of preparation, which required a very fine and homogeneous tea powder.

Dragon and phoenix discs

During the Sòng, half of the tea-producing regions sent tribute tea (gòng chá 貢茶) to the emperor. This tribute tea gave rise to the appearance of the so-called dragon and phoenix discs (lóng fèng tuán chá 龍鳳團茶), produced exclusively for the emperor. These pressed-tea discs were engraved on one side with a dragon and a phoenix on the other, mythological animals representing the emperor and empress, respectively, and were also called làchá 蠟茶, literally, "wax tea", due to their gleaming and shiny finish.

Illustration of a dragon and phoenix disc (lóng fèng tuán chá 龍鳳團茶) on both sides.

These tea discs were especially expensive and very arduous to produce. We will relate the process as described by James A. Benn in Tea in China, A religious and cultural history:

During harvesting, only the smallest shoots were collected, requiring many thousands of small leaves to form a single disc. The shoots were classified in grades according to the number of leaves per bud. For these discs only buds with one leaf or buds with two leaves were used. Subsequently, the leaves were rinsed up to four times to clean them, and then steam was applied, which was a delicate process, because if it was not applied in its proper measure, the flavour of the tea was compromised.

Subsequently, the leaves were cooled and excess water was removed. They were then left under a heavy press overnight to extract the juices, so that the resulting drink would not be too bitter. The next day, the leaves were crushed in a mortar and water was added to form a paste.

This paste was poured into a mold and heated, roasted and blanched repeatedly, and then dried over low heat. Then it was cured and smoked. The whole process required six to ten days for thin discs and ten to fifteen for thick discs. Once cured, the discs were again steamed and cooled quickly with fans. This process gave them the shiny appearance for which they were known as "wax tea"1.

But this tea was not yet ready to drink. As the discs were stored for some time, before being consumed, the tea had to be roasted to remove the moisture it could have absorbed, and this process was also delicate, since again it could ruin the taste of the tea if done wrong.

The appearance of paper money and the availability of credit facilitated the establishment of a mercantile agency dealing with the tea market, which traded on the so-called Tea Horse Road (Chá Mǎ Dào 茶馬道 or Chá Mǎ Gǔ Dào 茶馬古道), a network of routes that ran mainly between the provinces of Yúnnán 雲南 and Sìchuān 四川 and the Tibet region (for more information on this trade route, see our article Cha Ma Dao, The Tea Horse Road).

In court, refinement reached its maximum expression. Emperor Sòng Huīzōng 宋徽宗 (1082-1135) was passionate about tea, as well as a highly cultivated person with great artistic talent, and wrote one of the best extant works on tea: the Dàguān chá lùn 大觀茶論 ("Treatise on Tea in the Dàguān Era"). For Huīzōng, the way a person consumes tea reveals his true character, exposing his virtues or defects.

Emperor Sòng Huīzōng 宋徽宗.

This emperor considered the dragon and phoenix discs of the province of Fújiàn 福建 as the best in China, giving great fame to the region. He also led to a shift from extravagance and opulence in tea preparation to a simpler yet equally exquisite aesthetic, and gave special importance to knowledge of tea itself, including its production and cultivation.

Huīzōng also encouraged the spread of the jiànzhǎn 建盞 pottery of Fújiàn, the most famous during this period, and which led to the appearance of other types of ceramics that tried to imitate it. While in Táng light-colored pottery was preferred, to contrast with the colour of the liquid, black jiànzhǎn ceramics highlighted the white of the foam produced when whisking tea (we have already described this pottery in the article From "Eating Tea" to "Drinking Tea": Tea since Tang Dynasty).

Jiànzhǎn 建盞 bowl.

Diǎnchá

Before describing the process of preparing diǎnchá, let's take a few moments to introduce the most important utensils that were required.

The Chájù tú zàn 茶具圖贊 ("Illustrated Tea Utensils") of Shěnān lǎorén 審安老人, describes twelve utensils known as the "twelve knights" (shí'èr xiānshēng 十二先生), and divided into four categories: tea grinding instruments (niǎnchá yòngjù 碾茶用具), tea drinking instruments (diǎnchá zhǎn 點茶盞), whisking instruments (jī fú yòngjù 擊拂用具), and water boiling instruments (zhǔ shuǐ yòngjù 煮水用具). Next, we will dwell only on the most important of them.

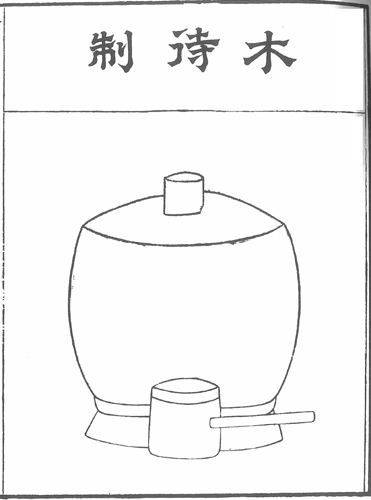

Breaking anvil (zhēnchuí 砧椎):

It consists of a mortar (zhēn 砧) and a mallet (chuí 椎, literally, "vertebra"). It is usually made of wood, and is used exclusively to break the tea disc into small, manageable pieces.

Illustration of a breaking anvil (zhēnchuí 砧椎).

Tea grinding wheel (chániǎn 茶碾):

It consists of an elongated container and a wheel with an axle. It was used to grind the pieces of the tea disc, passing the wheel over and crushing them against the container. However, it was not an instrument capable of obtaining a fine and homogeneous powder yet; for this, another instrument was needed.

The grinding wheel could be made of ceramic, stone, wood, gold, silver, copper, iron or other metals. During Sòng, silver was considered the best material, as gold was not hard enough, and other metals or stone could contaminate the taste of tea.

Tea grinding wheel (chániǎn 茶碾).

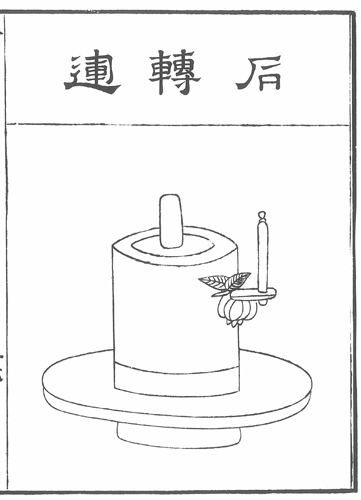

Tea mill (chámó 茶磨 o cháwéi 茶磑):

The tea mill was a stone mill capable of reducing tea to a very fine powder. This instrument appeared during the Sòng dynasty. During the Táng, grinders or mortars were also used to grind tea, but they were not specifically designed for that use, nor were they specifically called "tea mill" nor, more importantly, could they produce such a fine powder.

The development of this mill was related to the enthusiasm for dòuchá 鬥茶, "tea duel" (see below), in which participants competed to produce the whitest and most durable foam whisking tea.

There were several types of stone considered the best for making tea mills, of which the best was called zhǎngzhōng jīn 掌中金, "gold in palm".

Tea mill (chámó 茶磨 o cháwéi 茶磑). In the lower photograph you see the hole for the wooden handle, which is missing. The illustration above shows the complete object.

Black ceramic bowl (hēiyòuzhǎn 黑釉盞):

This cup is the bowl in which tea was whisked, served and drank. The black colour was considered ideal to highlight the white foam that was produced when whisking the tea.

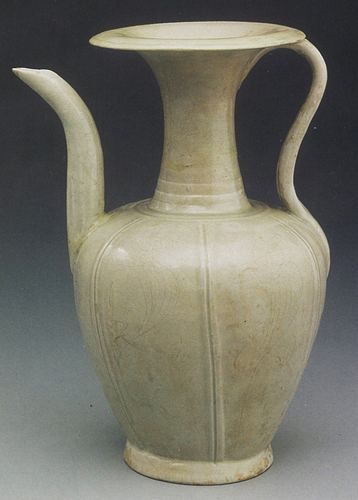

Boiling water ewer (chápíng 茶瓶 o tāngpíng 湯瓶):

Although these jars existed long before, until the Táng dynasty they had been used to serve wine and therefore were not specific containers prepared to boil water; They lacked handles and they were difficult to carry when hot.

In Sòng they had already evolved to meet the needs of diǎnchá, produced with a thin mouth ideal for pouring water when whisking tea, and achieved an exquisite production. The materials could be ceramic or stone, but the upper classes preferred those of gold or silver.

Boiling water ewer (chápíng 茶瓶 o tāngpíng 湯瓶).

Knowing the most important instruments used in the preparation of diǎnchá, we will now describe the process.

Preparation of diǎnchá:

According to Song Huīzōng's text, Dàguān chá lùn, diǎnchá consisted of the following steps: niǎn chá 碾茶 (grinding tea), luó chá 羅茶 (sifting tea), hòu tāng 候湯 ("waiting for soup", referring to heating water to the correct temperature), xié zhǎn 熁盞 (heating the bpwl) and diǎnchá 點茶 (whisking tea).

To prepare diǎnchá, the tea cake was first roasted over a brazier, and then a piece was taken, wrapped in paper and broken into pieces using the anvil. From there it was passed to the grinding wheel, where it was crushed into smaller pieces, and from there it went to the chámó or tea mill. In the chámó it was ground several times, until it became a very fine powder that was collected in a container with the help of a brush, to be sifted afterwards.

Grinding tea into fine powder.

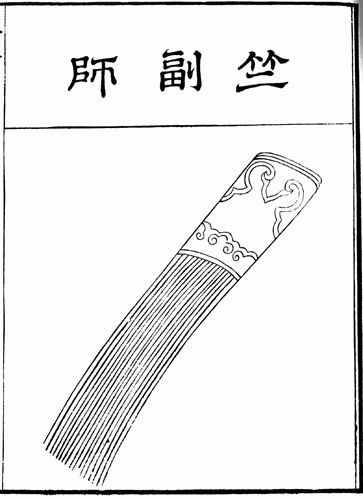

Then the water and implements were heated to the right temperature, the tea powder was placed in a black ceramic bowl or cup, which had also been heated over the fire, and hot water was poured while beating with a bamboo whisk (cháxiǎn 茶筅) to form a thick foam. The water had to be at the right temperature to form the foam. Finally, the cup was placed on a base (zhǎntuō 盞托) and the tea was ready to drink.

Illustration of a bamboo whisk (cháxiǎn 茶筅).

Bowl and stand (zhǎntuō 盞托).

This process of preparing tea was extremely difficult and required great skill and meticulousness, since if any of the steps were not done correctly, the final result was ruined. Moreover, given the large number of instruments required, this preparation was only possible among the upper classes, who often had several servants dedicated to this task.

In the Sòng dynasty, tea had become, in addition to a basic good for local consumption, a luxury product highly valued by connoisseurs of the social elite, and whose price was according to this category.

In the tea harvest during this time, quality prevailed over the quantity of the product, which was generally small. Plucking tea leaves in Fújiàn was a very sophisticated operation; in order not to contaminate the leaves with sweat and grease from the hands, the tender leaves were collected with the nails.

To all this exacerbated refinement was added the fever for dòuchá, the tea preparation competitions, described below.

Dòuchá:

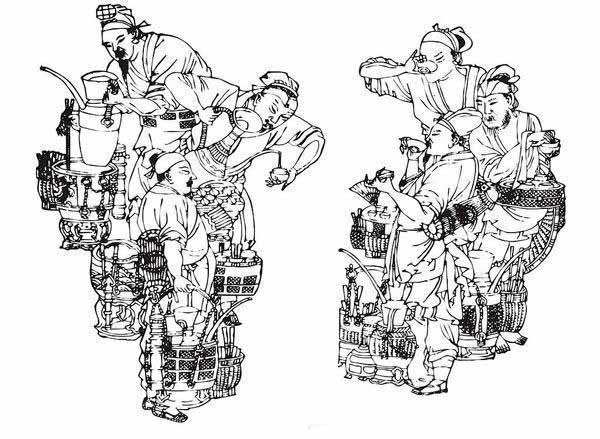

During this time the rise of dòuchá, "duels" or tea competitions, also known as míngzhàn 茗戰, takes place. Although these competitions seem to have emerged in Fújiàn already at the end of Táng, it is during Sòng when they reach great popularity, unleashing a general fever among educated people.

In dòuchá, several competitors competed before a judge to prove who prepared the tea with greater skill. Each participant strove to perform every step of the process perfectly, from roasting and grinding to whisking, while verbally exposing his actions or discussing the origins and method of production of tea, to demonstrate his knowledge and good taste.

The most relevant factor that demonstrated the skill of the competitor was the quality of the foam produced when whisking the tea. People of the Sòng era became obsessed with this foam, and poets described in their verses the beauty of bubbles. Emperor Sòng Huīzōng classified the colour of diǎnchá's foam into four grades: white, greenish, grayish and yellowish.

The whiter foam, which was the most desirable, and which was referred to metaphorically as "snow", was indicative of proper preparation and the use of the most tender leaves in the production of tea. To produce it, both the quality of the water and the quality of the leaves and the ratio of water to tea powder had to be taken into consideration, as well as the way to add the water and, of course, the ability to whisk the tea.

Green foam was a sign that not enough steam had been applied in the processing of the tea, while the grayish colour, on the contrary, indicated an excess of steam in the same process. Finally, yellowish foam indicated that the harvest had not taken place at the right time.

The size of the bubbles was also valued; for Huīzōng the ideal bubbles were so small that they resembled millet grain and crab eyes, and this sovereign believed that producing the best foam was not a matter of strength but of technique.

But the most determining factor, and by which the winner of the match used to be decided, was the time it took for the foam to dissipate. For the foam to last as long as possible, the tea had to be ground and whisked to perfection; otherwise it would quickly dissipate.

All this fever to obtain the most desirable foam gave rise to the appearance of the expression diǎnchá sānmèi 點茶三昧 (samadhi of diǎnchá). Samadhi is a Buddhist term that designates a high state of consciousness reached during meditation and, in colloquial language, was used to refer to an amazing ability. Of the most famous competitors of dòuchá it was said that they possessed the samadhi of diǎnchá. This expression, in addition to reflecting the connection between Buddhist language and tea, suggests that the preparation of diǎnchá required a deep meditative state.

In addition to competing to demonstrate the greatest skill in the preparation of diǎnchá, there were also competitions in which it was a question of guessing the origin or harvest season of the tea and even guessing the origin of the water used to prepare it, which could be from mountain spring, river or well.

Also, characters were sometimes drawn in the foam, or drawings of animals and plants, a practice known as "dividing tea" (fēnchá 分茶).

Dòuchá became very common among educated people. Competitions were held to commemorate special occasions or gatherings, and it became a regular pastime at the imperial court.

As tea preparation was considered an elegant and refined activity, the ability to produce the best foam caused the admiration of others, and even if the competition was not won, only participating already brought great prestige. The people of Sòng took these competitions very seriously, and those who achieved fame as skilled preparers could even reach official positions in the production of tribute tea.

The practice of dòuchá survived even during the Míng 明 dynasty, when the consumption of loose leaf tea had replaced diǎnchá as a general practice.

All this sophistication, from the making of the tea discs to the preparation of diǎnchá, and considering all the instruments that were required, was surely beyond the reach of ordinary people.

It seems that it was at this same time, and perhaps related to the high price of the product, that loose leaf tea (sànchá 散茶) began to gain popularity. Given the ubiquity of tea, humblest consumers demanded a more affordable product.

With loose leaf tea, the preparation process was greatly simplified and the same leaf yielded more ammount of drink, since it was not ingested with the liquid. Due to the different processing methods, the taste was probably different from today's tea.

However, this method remained during Sòng relegated to the lower layers of society and would not be definitively established as the norm until the beginning of the Míng dynasty.

The arrival of tea in Japan

During the Táng dynasty, tea had already crossed the sea to Japan as a gift between sovereigns. There it was consumed as an exotic product and then forgotten.

It wasn't until the Sòng dynasty that tea came back to Japan to stay. The Japanese inherited the methods of production and preparation of tea from Sòng China, and even today the preparation of Japanese matcha (mǒchá 抹茶) is similar to the preparation of diǎnchá in the Sòng dynasty.

In the same way, while the application of steam to stop the oxidation of green tea would practically disappear from China during the Míng dynasty, in Japan it remains the most widely used method even today, accounting for the main differences between Chinese and Japanese green tea.

To be continued...

In the next article we will see the drastic changes brought about by the Míng dynasty and we will follow the evolution of tea culture to the present day.

Notes:

1. Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History, James A. Benn. University of Hawaii Press, 2015. P. 120