This article is a continuation of History of Tea and its Culture (III): The Sòng Dynasty.

Tea culture in the Míng dynasty

The beginning of the Míng dynasty sees the end of disc-pressed tea and marks the beginning of the era of loose-leaf tea (sànchá 散茶). Tea production had already reached a level of sophistication and refinement during the Sòng 宋 that, although difficult to sustain, was maintained during the Yuán 元 dynasty.

This type of production not only made the product more expensive at stratospheric levels, to the point that dragon and phoenix discs (lóng fèng tuán chá 龍鳳團茶) could cost more than their weight in gold, but also the process of preparing the drink was also too laborious, easy to ruin and not accessible to ordinary people.

The first Míng emperor, Zhū Yuánzhāng 朱元璋 (Hóngwǔ 洪武), was an austere man who came from a poor family, one of the few emperors of China to rise to power from such humble beginnings. Hóngwǔ saw diǎnchá 點茶 and all that it entailed as superfluous and empty. Accustomed to long military campaigns and consuming tea the way the poor did, simply adding a few tea leaves to hot water, he abolished the old system of production to free producers from the burden of such elaborate production and make the product accessible to ordinary people.

One of his sons, Zhū Quán 朱權, following the imperial order to "abolish pressed discs in favor of the loose leaf" (fèi tuán gǎi sàn 廢團改散), developed the current method of infusion, whereby the leaves are removed from hot water to consume only the liquid.

Zhū Quán 朱權.

Hóngwǔ also banned the use of steam in tea processing, which encouraged the development of new processing methods. From then on, producers began to use woks and pans to deactivate the enzymes (shāqīng 殺青) that produce the oxidation of the leaves. This had an important impact on the taste of tea, since when higher temperatures are reached in the wok, certain bitter components of the leaf are destroyed sweetening the final flavour of the drink.

Shāqīng 殺青 (enzymatic deactivation) has been done on woks or pans since the time of the Míng 明.

To this day, almost all teas in China are produced in this way (except for a couple of varieties that survived the old-fashioned way), but in Japan, which inherited the production method of Sòng China, steam is still used in the production of green tea.

These changes made tea more accessible to all social levels and further encouraged its consumption.

It is believed that sometime during the Míng dynasty yellow tea (huáng chá 黃茶) appeared due to an error during the processing of green tea.

Many of the most renowned teas of the Míng period were grown in or around Buddhist monasteries. Monks continued to play an important role in the development of tea culture. In the Jīnshā 金沙 ("Golden Sand") monastery, in Yíxīng 宜興, Jiāngsū 江苏 province, where monks made pottery from a locally obtained clay, a new style of pottery known as Yíxīng zǐshā 宜興紫砂, "Yíxīng purple clay", or simply zǐshā, appeared at this time.

The Legend of Gong Chun and Yixing Pottery

It is said that a young servant of a wealthy family, named Chūn 春, whose patron was a great connoisseur of tea, often visited the monastery of Jīnshā, where he once discovered monks making pottery.

One day, he discovered that the excellent taste of the tea the monks drank was due to the material of the pots where they prepared it, which were from the local pottery. Chūn became interested in the production of this pottery, and began to receive instruction from the monks, showing great talent.

After a long time of study, he finally produced a teapot of special quality, to which the abbot of the monastery gave the proper name of Gōng Chūn 供春. Chūn would later devote himself entirely to the production of teapots of this clay, known as zǐshā, developing his own style and increasing the fame of the Jīnshā monastery. Over time, everyone began to refer to him as Gōng Chūn.

Gōng Chūn 供春 style teapot.

Gōng Chūn is considered the father of Yíxīng pottery. He reduced the size of teapots and popularized their use in the region, basing his style on an aesthetic of simplicity and imitation of forms of nature.

Representation of Gōng Chūn 供春.

Regional pottery, which uses different types of clay encompassed within what is known as "purple clay", is considered especially suitable for tea preparation due to its porosity and its temperature-holding capacity. The pores of the teapots of this clay absorb the essential oils of the tea, acquiring over time a character of their own that brings complexity to the flavour of the tea.

Yíxīng would eventually give rise to many famous ceramists, including Huì Mèngchén 惠孟臣, who is considered the father of modern Yíxīng pots.

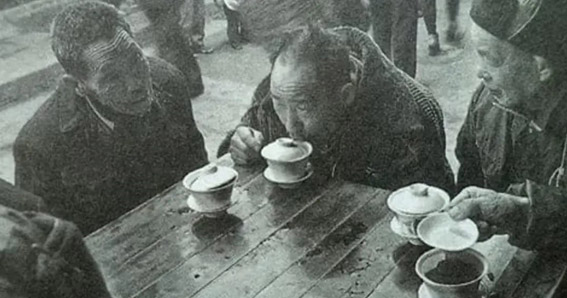

Also at this time appears the gàiwǎn 蓋碗, which consists of a bowl with a lid and often with a saucer or stand. In the bowl the tea leaves and hot water were added, and it was drunk directly from it by holding the plate with one hand and setting aside the leaves with the lid. This form of use differs from the current method, in that the liquid is separated from the tea leaves by decanting it in a separate container, a method that would not appear until the Qīng 清 dynasty.

Group of men drinking tea directly from the gàiwǎn 蓋碗.

Among the most famous teas of the Míng dynasty, Lóngjǐng 龍井 ("Dragon Well") and Wǔyí 武夷 are among those considered the top five. Both teas are still very famous today.

It is said that the real Lóngjǐng, coming from the Dragon Well next to the village of the same name (and formerly called Lónghóng 龍泓) in Zhèjiāng 浙江, grew only in an area of less than one hectare, and the teas produced outside it, although they bore the same name, were inferior in quality. It was difficult to find the authentic Lóngjǐng on the market, so many upper-class enthusiasts traveled to the region to purchase it in their place of origin.

On the other hand, tea from Mount Wǔyí in Fújiàn 福建 was categorized by harvests and growing areas, giving rise to about a hundred categories, classified according to the amount of sun, rain, wind and dew they received.

Also, scented tea, flavoured with flowers and other plants, such as jasmine tea (mòlìhuā chá 茉莉花茶), seems to have its origin in the Míng dynasty, although at first these blends were prepared based on their medicinal properties.

At this time, drinking tea became an essential activity for literati and scholars, who emphasized the spiritual aspects of tea over its material or medicinal aspects. In social gatherings, tea was already the socializing drink par excellence, preferred even over alcohol.

Tea culture from the Qing Dynasty to the present day

The Qīng dynasty (1636–1912), of Manchu origin, was the last dynasty of the Chinese imperial era. Spanning three centuries that saw a last golden age and later a progressive decline, in which the conflict and the weakening of China against the Western powers stands out, it would end with the establishment of the Republic of China (Zhōnghuá mínguó 中華民國) in 1912.

Between the end of Míng and the beginning of Qīng appears black tea (hóngchá 紅茶), and in the following centuries appear wūlóng 烏龍 and white tea (báichá 白茶), completing what are considered the six great varieties of tea (liù dà chá 六大茶).

Appearance of black tea

A legend tells how black tea was discovered when on one occasion, in a village on Mount Wǔyí, while the villagers were processing tea, a group of bandits appeared and looted the village. The producers had to escape abandoning their task and the tea leaves were left and exposed to the smoke of the fires that occurred.

The next day, when the villagers were able to return, the leaves had oxidized and acquired the smell of smoke. In an attempt to profit from this spoiled tea, they took it to ports where it was traded with the West and Europeans bought it. This tea was a success in Europe, and Westerners demanded more, so the Chinese began to produce it intentionally.

The Chinese called oxidised tea "red tea" (hóngchá 紅茶), because of the colour of the brew.

This type of tea is known in the West as "black tea" because of the colour of the leaves.

At this time, the tea processing formula left China. The country had already evolved and accumulated knowledge in the methods of cultivating, harvesting and processing tea for more than a millennium. Although it was already known before by the mentions of some travelers, it was in the early seventeenth century when the Western powers began to be interested in this exotic product, and the export of Chinese tea flourished for a time.

The Chinese jealously guarded the secrecy of tea production, maintaining their monopoly on trade. Although Japan also produced tea, the archipelago was going through centuries of isolation and was completely closed to foreign contact, so Western countries had to turn to China if they wanted to import the coveted product.

Until the nineteenth century, Western powers, especially the British Empire, acquired from China not only tea, but also other exotic herbs and plants, silk, furs, porcelain and other handicraft products. Between 1760 and 1842, all foreign trade was to pass through the city of Guǎngzhōu 廣州 (Canton), where this trade was regulated and supervised by the Chinese authorities.

While Europeans craved large quantities of goods from China, the Qīng government was not interested in trading European goods, and demanded that foreigners pay for all Chinese goods in silver. This demand caused the coffers of the British Empire to be emptied at a great speed.

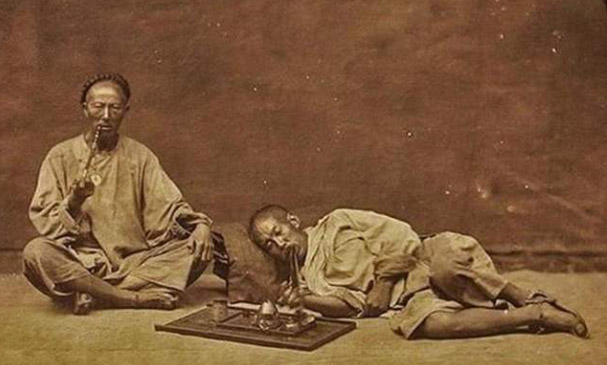

In order to continue to satisfy the insatiable European demand for Chinese products, the British decided to start bringing opium to China from their colonies in India, to exchange it for Chinese goods. The opium trade was soon banned, but Europeans continued to smuggle it in.

Opium use and addiction caused great economic and social damage to China, despite attempts by the Qīng government to eradicate it. The Manchu government confiscated and destroyed a large shipment of opium, which unleashed several skirmishes, and tensions eventually led to the so-called Opium Wars (Yāpiàn Zhànzhēng 鴉片戰爭), the first between 1839 and 1842 between Britain and China, and the second between 1856 and 1860 between Britain and France, on the one hand. and China on the other.

Opium use spread in Qīng China like an epidemic.

These wars were a disaster and were a terrible humiliation for the Manchu regime, which upon being defeated was forced to grant trade privileges and territories to the European powers, including the cession of Hong Kong 香港 and the opening of ports such as Shànghǎi 上海. They even forced the Chinese to accept the opium trade, which continued to create thousands of addicts, people unable to work or serve in the military, and deteriorate Chinese society. China's opium problem was the largest national drug addiction a country has ever suffered.

Although we know these conflicts as Opium Wars, because the illegal trade of this substance was the final trigger of the conflict, these wars were also caused by Western interest in Chinese products, tea being undoubtedly one of the most important.

Robert Fortune

In the 1820s, hoping to stop relying on the supply of tea from China, the British Empire was experimenting with tea plants indigenous to the Indian region of Assam, belonging to the subspecies camellia sinensis assamica. However, the result could not be compared to the aroma of Chinese tea to which Europeans had already become accustomed and, in fact, it was dismissed thinking that it was a different species of plant.

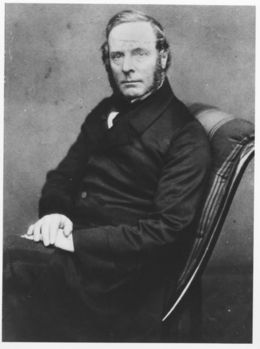

A few years later, while the conflict was growing in the Canton area, and finally the Opium Wars were being fought, a Briton went into China, beyond the permitted limit of the city of Guǎngzhōu, and would end up "stealing" the coveted secret of tea production. This man was Robert Fortune.

Fortune was a Scottish botanist, who in 1843 was sent to China to collect exotic plants. Fortune learned Mandarin well enough to pose as a Chinese from remote provinces, grew a biànzi 辮子, the Manchu queue that all subjects of the empire were required to wear, and went beyond the established limits of the city of Canton under a false name. Disguised as a merchant from the northwestern regions, he toured the provinces of Guǎngdōng 廣東, Fújiàn and even Jiāngsū.

Fortune not only managed to get hold of tea plants of the subspecies camelia sinensis sinensis, whose foreign trade was prohibited by the Chinese authorities, but also brought to British India Chinese workers who were experienced in tea production. Although most of the tea plants that Fortune took ended up dying, the knowledge of the producers was key in the development of the tea industry in India, with the local subspecies of camellia sinensis assamica. Today most Indian teas are produced from this variety, except for Darjeeling, which is produced from the Chinese small-leaved subspecies.

Until then, the English had believed that green and black tea came from different plants, following Linnaeus' botanical classification as thea viridis and thea bhorea, respectively. Fortune's work opened the eyes of Western botanical science, classifying tea as a species of the camellia genus in the early twentieth century.

Robert Fortune.

The result of Fortune's enterprise was that Europe ceased to depend on China for tea supplies. With that, the Chinese monopoly ended and a lucrative new business for the British Empire began. At first, all the tea produced in India was for export to Europe, but when the price dropped the Indians started drinking it too, with India being one of the largest consumers of tea in the world today.

Later, the tea industry also extended to the British colony of Ceylon, present-day Sri Lanka. Both India and Sri Lanka are two of the largest tea producers in the world today and, although the quality cannot yet be compared to that of the tea produced in China, significant progress is being made.

Robert Fortune not only introduced tea to the West, but also many other hitherto unknown plant species.

Although Europe now had tea, the greatest developments in this field continued to take place in China, a country that had millennia of knowledge accumulated in tea production.

Other important innovations of the Qīng era were the reduction of the size of accessories and the emergence of gōngfuchá 工夫茶 style, in addition to the development of local ceramics such as Cháozhōu 潮州 and Yúnnán 雲南, influenced by Yíxīng pottery. The clay of this region began to run out, and a kilogram of it reached its weight in gold, so counterfeits and products with mixed clay began to be produced.

In this same field, it is worth mentioning the creation of the "eighteen styles" of Yíxīng ceramics by the famous artist Chén Mànshēng 陳曼生 and manufactured by the ceramist Yáng Péngnián 楊彭年, known as the "eighteen styles of Mànshēng" (Mànshēng shíbā shì 曼生十八式).

The names of tea:

In the eighth-century Chá Jīng 茶經, "Tea Classic," Lù Yǔ陸羽 lists five Chinese characters for this plant: chá 茶, jiǎ 檟, shè 蔎, míng 茗, and chuǎn 荈. In addition to these names, tea receives other denominations in different dialects of China.

On its way to the West, tea followed the main trade routes: on the one hand, the land route, north through Mongolia and Russia and from there to Europe, or through Central Asia. On the other hand, the sea route, starting from the ports of southern China.

The names by which European countries call tea tells us which route it followed, starting from the port of acquisition. These names fall into two main categories:

- Names derived from the Mandarin chá: indicate a trade through the land route, from cities in northern China such as Xī'ān 西安 or Běijīng 北京.

- Names derived from the term tê of the mǐn 闽 dialects of southern China: indicates a sea route from the ports of Fújiàn and Canton, mainly to the British Empire.

In recent times, the tea industry has continued to develop. In 1973 shú Pǔ'ěr 熟普洱 was invented, a type of hēichá 黑茶 produced in the Yúnnán region, whose fermentation is produced artificially in an accelerated manner. This process mimics the natural fermentation of tea, reducing its aging process from several years to just sixty days.

Originally, the terms shēng 生 (raw) and shú 熟 (ripe) were used to refer to tea before and after its natural maturation, a microbial fermentation process that took years of aging. After the invention of the artificial process, these same terms came to refer to the maturation method.

Conclusions

Tea has been an essential part of Chinese culture for many centuries, bringing together practical, aesthetic, economic and spiritual aspects.

Throughout nearly two thousand years of history, humans have consumed tea in different forms, from medicine in edible form to a healthy and pleasurable drink, and tea has unleashed passion at different times and in various ways.

Today, China remains the world's largest producer, exporter and consumer of tea, even though many other countries also produce it. It is the country where the largest number of varieties of higher quality is produced.

The consumption of tea has already spread to all corners of the globe, however it is still in China where we find its deepest roots, its most complex meanings and a more elaborate culture regarding this plant that has formed over many centuries.

Although this is not a complete history, we hope that the reader has found useful information to form a global idea, and to have offered valuable clues so that he or she can continue to investigate and deepen this fascinating culture.

Sources:

- Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History, James A. Benn. University of Hawaii Press, 2015.

- The Rise of Tea Culture in China: The Invention of the Individual, Bret Hinsch. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

- Thanks to Ryan Hollibaugh from Pei Chen Tea Palace (Buenos Aires, Argentina) for the information provided.