Introduction

For most of Chinese history, archery (射藝 shèyì), whether with bow or crossbow, was the main martial discipline and the most important form of combat in warfare. Even after the appearance of the first firearms, archery maintained its primacy on the battlefield until well into the nineteenth century.

In addition, archery is a discipline that since ancient times has been associated with self-cultivation and, therefore, also considered as a Dào 道, that is, a spiritual path; in this sense it is known as shèdào 射道.

Historical background

Since always, and for all remote societies, bows and arrows have been hunting instruments. Although bows and arrow shafts are made of perishable materials and do not persist as archaeological remains, there are remains of arrowheads made of bone or stone, first, and bronze later. The oldest archaeological evidence of archery in China dates back approximately 28,000 years.

However, by extension, bow and arrows would also be used for war. As proof of this, skeletons with bone arrowheads embedded in them have been found, from the Neolithic.

In other skeletons, multiple arrowheads have been found clustered on the torso, indicating that the dead person was buried with them, and that the victim would have been ritually killed with arrows. Since executing the victim with a short weapon would have been more efficient, this type of ritual death speaks of a symbolic meaning of archery since prehistoric times, beyond its practical use.

Chinese and Central Asian bows evolved from simple wooden sticks with animal gut strings to compound bows made of bone, tendons and wood glued together.

First dynasties

In the Shāng商 and Zhōu 周 dynasties, archery seems to be associated with aristocratic elites, possibly due to the cost of manufacturing the bow. On the other hand, after the sedentarization and settlement of the population and the beginning of agriculture, hunting became an activity of the upper class, more unoccupied.

During Shāng, the use of chariots was introduced on the battlefield. Chariot warfare consisted of driving horse chariots from which arrows were shot at select targets. Both archery and chariot driving needed a long training time to achieve good performance; moreover, shooting from a moving chariot would have taken years of training. This time was only available to the upper classes, freed from agricultural work.

Archery as a way of self-cultivation

Since the first Chinese dynasties, archery competitions were practiced among the aristocratic classes. These events were highly formalized; in Zhōu they became a social and spiritual act that demonstrated the inner development of the practitioner. This vision of archery would remain for most of imperial China.

It is noteworthy that archery is the first martial discipline associated with self-cultivation, a mental concentration that transcends the ordinary.

In war archery, physical strength was essential when pulling the bow, so that the arrow was shot with enough power to penetrate the target. However, after King Wǔ武 of Zhōu, archery competitions were detached from the purpose of penetrating the target, valuing more precision and etiquette, considered a reflection of the mental state of the practitioner. For Confucius (孔夫子 Kǒngfuzǐ), ritual execution and accuracy prevailed over piercing ability and, therefore, over the use of force.

This view on archery competitions made them accessible to the civilian aristocracy, who did not have the necessary training to pierce the target, and not only to the military elite. Otherwise, uneducated military archers would have appeared above Confucian knights and scholars. The correction of form showed the internal cultivation of the person and was not, therefore, a mere ostentation of the strength of the war archer.

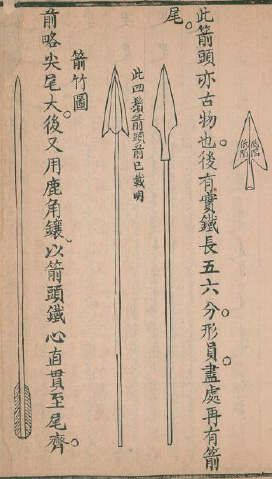

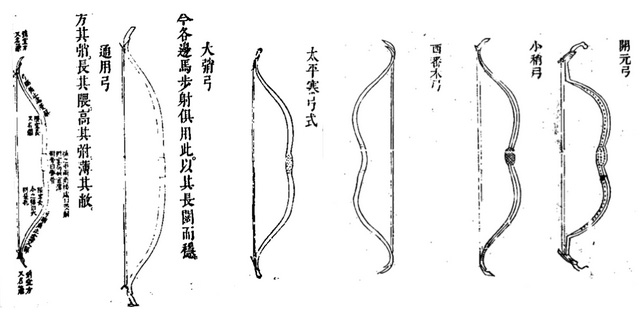

Different types of bow.

For post-Confucius thinkers, archery will continue to occupy the central place as a martial skill par excellence, despite the emergence of other weapons.

As mentioned, archery competitions were extremely formal events, where what was demonstrated was above all the conduct of the participants. Although chariot racing and wrestling were also competitive disciplines during the Zhōu dynasty, only archery competitions were used to assign court positions.

Archery became for Confucian thinkers a measure of inner development. Like correct behavior, success was the result of one's own discipline in reproducing the right form, without any connection to the other competitors.

Beyond the Confucian emphasis on the correctness of form, the idea that mastery in archery required a transcendent state of mind developed over time, and therefore this discipline was conceived as the path to a high state of mind. This idea appeared in the writings of Zhuāngzǐ 莊子 and Lièzĭ 列子.

The archery of Lièzĭ

In the Lièzĭ there is a story according to which Master Liè was demonstrating his archery to a certain Bóhūn Wúrén 伯昏無人. Lièzĭ was so skilled that he could place a cup of water on his elbow, and pull the bow without spilling a drop, and he was also so fast that, after shooting an arrow, he had already put the next in its place.

However, this ability does not impress Bóhūn Wúrén, a legendary character representing Dào 道 itself. Wúrén (literally, "non-person"), urges Lièzĭ to climb a mountain and shoot from the top of a cliff. When Wúrén stood with half of his feet sticking out of the abyss, Lièzĭ lay on the ground, sweating in panic.

In this story, Wúrén shows Lièzĭ that, although he has reached the physical ability of archery, he has not yet reached the Dào. Lièzĭ's inability to shoot from the top of the precipice is because his mind is tense; he has attained external ability but has not mastered the subtle aspects.

Lièzĭ 列子.

This is one of the first indications of the idea that martial arts, through perfection of skill, can lead to a perfection of the mental state. It is noteworthy that this idea appears long before Chán 禪 or even the arrival of Buddhism from India. In martial arts, physical ability decreases with age, but mental perfection remains.

Archery in war

As we have already mentioned, chariot archery was based on firing a small number of arrows at specific targets, that is, at enemy officers, and not on the massive firing of arrows at the whole of the troops. In the Warring States period (戰國時代 Zhànguó Shídài), the effectiveness of archery from chariots declined, for reasons possibly linked to changes in modes of warfare and the appearance of massive armored infantry.

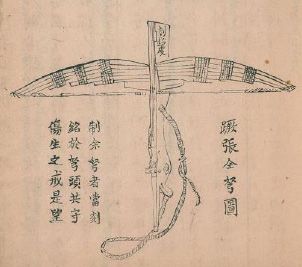

To this was added the emergence of the crossbow in the late Spring and Autumn period (春秋時代 Chūn-Qiū Shídài). The crossbow, although slower than the bow, was easier to use for troops with less training and had greater piercing power. The crossbow would never acquire the cultural and symbolic significance of the bow, and throughout history it remained an eminently practical weapon linked to the battlefield.

Illustration from a crossbow manual.

Until then, archery had been the monopoly of the aristocracy. However, these changes in the war were a setback to the upper classes, as they were displaced as kings of the battlefield by the mass of ordinary soldiers.

The mass struggle and the crossbow brought the monopoly of the common people, which in some ways posed a challenge to the established political order. Confucian thinkers resorted to a supposed moral superiority to justify the rule of the elites, and the elites reaffirmed themselves in archery as a way of expressing the superiority of their conduct.

Archery after the Hàn dynasty

During Hàn 漢, the importance of archery remained intact in both war and competition, and was included in the so-called Hundred Games (百戲 bǎi xì), but there were no changes in the way it was practiced.

During the Three Kingdoms (三國 Sānguó), archery on horseback was identified with the martial arts of the steppe peoples, where archery practice was part of ordinary life. For them, archery was a daily necessity in their nomadic and hunting life; they were trained since childhood and were skilled shooters by nature.

When large numbers of these nomadic warriors moved south, it became necessary in northern China to train troops in archery to face them, so the regular practice of this discipline grew in importance, and training camps were established for its practice both on foot and on horseback.

Emperors promoted archery competitions and hunting, and the emphasis on strength to pierce the target returned. It was also important to be able to shoot left and right from horseback.

Thus, the values of archery, both on foot and on horseback, typical of the steppe peoples of the north, were absorbed into Chinese culture, although for the Chinese elites this skill had to be trained specifically for war, since it was not part of the natural way of life.

Due to the armed conflicts with the peoples of the steppe, who made charges on horseback and retreated riddling their pursuers under a rain of arrows, the mobility of the cavalry was emphasized and this practice became the preferred mode of war, over the armored cavalry, slower and more ineffective against the nomads.

During Suí 隋 and Táng 唐, archery maintained its central importance in military practice, and was an ability expected of any court official.

The Sòng dynasty and the rejection of martial arts

During the Sòng 宋, archery maintained its paramount importance among the different combat arts. Huá Yuè 華嶽, poet and martial artist of the time, regarded the bow as the first of the thirty-six military weapons, and archery as the first among the eighteen martial arts.

During this time there were great cultural changes. First, an increase in the emphasis on the crossbow as a form of identification with the culture of China. Second, a preference for the civil over the martial among the ruling elites, which led to contempt for martial practice and the abandonment of archery among the civilian upper classes. The reasons for these changes are social, cultural and political factors, not based on effectiveness.

Increase in importance of the crossbow:

The crossbow had been a distinctive Chinese weapon and was virtually unknown among the steppe peoples. The use of the crossbow highlighted the fundamental differences between steppe nomads and sedentary Chinese.

After the retreat of the Sòng to the south in the face of the advancing jurchen (Nǚzhēn 女真) and their takeover of northern China, these differences increased. In the south it was very difficult to get and keep horses, and the offensive power of the Sòng army was weakened. Instead, its defensive power lay with naval forces and fortifications on the Huái 淮 River, where the crossbow was more effective than the bow.

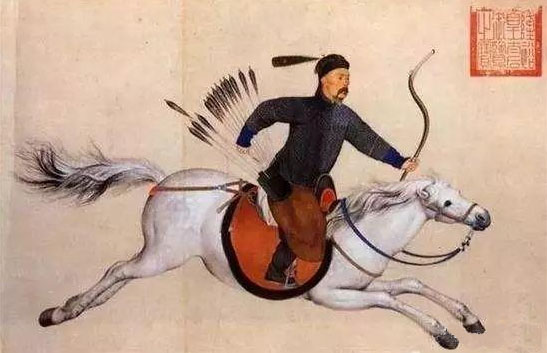

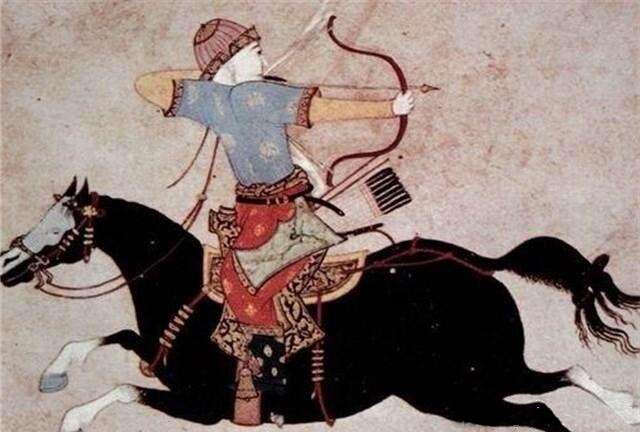

Jurchen archer on horseback.

Again the physical strength to pull the bow and crossbow were tests required for Sòng soldiers, and demonstrated their martial ability. The crossbow's weakness was its low rate of fire, so that it could only be used from fortified positions, or on the battlefield in conjunction with bows and solid infantry formations.

It was the Chinese cultural identification of the Sòng dynasty that led to this elevation of the crossbow above the bow.

Illustration of a soldier firing a crossbow.

Abandonment of archery among the elites:

During the Sòng dynasty, there was a revaluation of the civil (wén 文) and martial (wǔ武) principles, which gave greater prestige to civil servants and men of letters than to those who were dedicated to martial arts, so that the latter were considered as belonging to a lower social category.

In this way, Chinese civil society progressively dissociated itself from all martial practice. Archery, which for Confucius had been especially important as a way of internal cultivation and as a sign of self-improvement, ceased to be practiced among the ruling classes.

These elites, despite their contempt for the steppe peoples, which they considered barbarians, did not even learn to use the weapon that most distinguished them from them, the crossbow.

However, while the Sòng elites rejected martial arts, the local communities that suffered the looting of the peoples of the steppes devoted themselves to martial practice in order to defend their villages, in the face of the government's inability to guarantee security. Some archery societies (gōngjiàn shè 弓箭社) appeared there, which were often regarded by the elites as equal to the barbarians.

A brief resurgence of archery: the Yuán dynasty

In the thirteenth century, China fell under the Mongols and became part of the empire of Genghis Khan. Later, after the division of this empire, Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis, established in China in 1271 the Yuán 元 dynasty, claiming succession from the previous Chinese dynasties.

Although the Mongol rulers adopted Chinese culture, archery on horseback remained of vital importance to them, constituting the centerpiece of their martial arts.

For the Mongols and other steppe peoples, archery was not only a practical art, but also had religious and spiritual implications: it could ward off evil spirits and attract rain. It was also the basis of life in the steppe, being essential for both hunting and combat, and an essential part of the cultural identity of these peoples.

The Mongols, as a way of maintaining their authority and preventing rebellions, restricted the practice of martial arts among the hàn Chinese, including archery, as well as access to weapons such as bows and arrows.

The Yuán dynasty disintegrated almost a century after its founding, marking the end of this brief resurgence of archery among elites.

The decline of archery

During the Míng 明 dynasty (1368-1644), bow and crossbow archery continued to be key in the army, despite the existence of firearms. However, it never regained its importance among the civilian elites, who had abandoned its practice during the Sòng.

Despite archery's ancient association with self-cultivation, the elites of the Míng dynasty chose straight sword (jiàn 劍) fencing as a way to show their refinement.

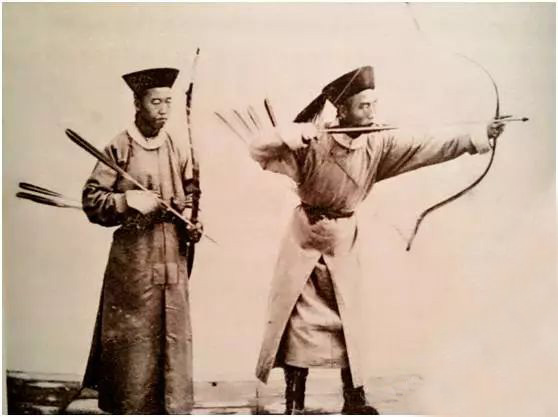

Manchu archers

With the establishment of the Qīng 清 dynasty, again a village linked to the ways of life of the steppes, archery may have regained its prestige. However, European military practice and industrial warfare made this practice obsolete in the military field.

Archery would never regain its prestige and remained archaic. Even after the twentieth century, when Chinese martial arts, obsolete in war, were revalued as practices linked to self-cultivation and spirituality, archery in China no longer enjoys the preeminence it has, for example, among Japanese martial arts.

Sources:

Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Peter A. Lorge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.