Introduction:

In today's Chinese martial arts the value of muscle strength is secondary to other qualities such as speed, elasticity and relaxation. No Chinese martial arts system boasts of making use of muscle strength. However, the value given to force has not always been the same. In ancient times, muscle strength was more valued as an attribute of any man of arms. As a way to show this strength, competitions such as "cauldron lifting" (扛鼎 kāngdǐng) were organized, which we will talk about on this occasion.

Ding (cauldron):

A dǐng 鼎 is a bronze cauldron or vessel used in ancient times both for practical uses, such as cooking and storing food, as well as for ritual and ceremonial uses. Dǐng is sometimes translated as "tripod" or "three-legged cauldron", although this is not always the case. The rounded cauldrons had three legs, but there were also quadrangular in shape with four legs, although in this case they are called fāngdǐng 方鼎; in both cases cauldrons have two ears or handles.

Cauldrons are very heavy objects, some reaching several hundred kilograms. The heaviest found to date is known as Hòumǔwù dǐng 后母戊鼎, dating from the late Shāng 商 (1300-1046 BC), is 133 cm tall, with a mouth of 112 x 79.2 cm and weighs 832.84 kg.

The cauldron known as Hòumǔwù dǐng 后母戊鼎, the heaviest found so far.

Cauldron lifting:

Cauldron lifting became popular during the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代 Chūn-Qiū Shídài, 771-476 BC) and the Warring States Period (Zhànguó Shídài 戰國時代, 475-221 BC).

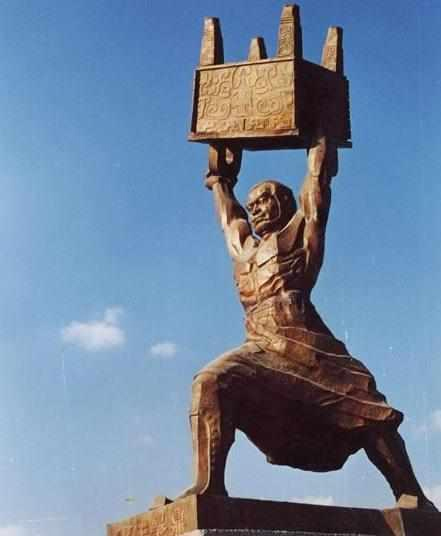

Statue of Xiàng Yǔ 項羽, ruler of the kingdom of Chǔ 楚,

famous for being able to lift heavy cauldrons. Sùqiān 宿迁, China.

Although the cauldrons that were lifted were obviously not as heavy as the Hòumǔwù dǐng mentioned above, there is written record of lifting cauldrons of more than two hundred kilos. Although at present day greater weights can be lifted, it must be taken into account that current athletes carry a training and diet regimen specifically designed for this task, and that they also lift weights that are designed solely and exclusively to be lifted.

In contrast, a bronze cauldron was not designed to be lifted; moreover, its shape and not so much its weight made cauldron lifting a task not only difficult but also risky.

To show this riskiness, what happened to King Wǔ of Qín 秦武王 in 307 BC serves an example. This king, named Yíng Dàng 嬴蕩, ascended the throne at only nineteen years old, and was known for his strength. When he had only been reigning for three years, he and an officer named Mèng Shuō 孟說 decided to measure their strength by raising a cauldron known as Lóngwén Chì dǐng 龍文赤鼎. When King Wǔ was lifting the cauldron, it slipped and fell on him crushing his leg, which caused a great hemorrhage and his death shortly after.

The court blamed Mèng Shuō, the other participant, for having taken part in the contest, and sentenced him to death along with the rest of his family. It is not written whether Mèng raised the cauldron or not.

During the Hàn漢 dynasty (202 BC-220 AD), in which the development of the economy and political stability allowed the emergence of recreational activities, cauldron lifting reached its maximum popularity, an official position was appointed in charge of these competitions, and this discipline was included among the so-called One Hundred Games (Bǎixì 百戏), a variety of entertainment shows.

Winners of major competitions were awarded honorary titles, and it was not unusual for official positions to be granted to men who stood out for their physical strength. In addition to lifting bronze cauldrons, other ways to demonstrate strength was by lifting large rocks and wheels.

Conclusion:

The idea of the importance of physical strength continued in the Chinese mentality until the twentieth century. In the founding story of Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 which has been transmitted orally, it is said that on one occasion Chan Heung 陳享 trained by "kicking stones" upwards and hitting them as they fell. His teacher Choy Fuk 蔡褔, unimpressed, asked him to move a millstone.

Does this mean that even for the founding master of Choy Li Fut physical strength was a major element in martial arts? Is it possible (and this is only our conjecture) that it was the contact with Westerners, more physically corpulent than the Chinese, already in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that made them seek an alternative to mere physical strength, where most Westerners would surpass them?

At the moment, we do not have enough information to answer this question. But it is clear that it was this era that would shape the image of the so-called traditional Chinese martial arts as we know them today, including their association with Qìgōng 氣功 systems or internal energy training, which place more value on internal work than on developing physical strength.

Although cauldron lifting competitions are long gone, the expression "lifting the cauldron" remains in colloquial language as a metaphor for taking control of state power or the ability to bear great responsibilities.

Sources:

- Sport and Physical Education in China, James Riordan and Robin Jones. Routledge, 1999.

- Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Peter A. Lorge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.