Introduction

The Fóshān 佛山 Hung Sing 鴻勝 school opened its doors in 1848 as one of the schools under the umbrella of Chan Heung 陳享, with Chan Din-Jau 陳典尤 and Chan Din-Wun 陳典桓 in charge. The school had to close in 1854 during the Red Turban Rebellion (Guǎngdōng hóng bīng qǐyì 廣東洪兵起義), and it would not be until 1867 that it reopened its doors, this time under the leadership of Cheong Jim 張炎.

It was he who gave Fóshān Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 its distinctive character, splitting from the branch practiced by Chan Heung and the rest of his students, and constituting a style of its own.

Cheong Jim's successor in charge of the Hung Sing school was Chan Ngau Sing 陳吽盛, who continued cementing the school's reputation, making it one of the most membered martial arts institutions in the city.

The Choy Li Fut schools

In the article "Chan Heung, Founder of a New System", we saw what martial arts teaching was like in Chan Heung's time, and what the profile of the students was like.

It is worth remembering here that those who sought private instruction in martial arts were, for the most part, peasants who had to defend themselves from looting; private escorts, opera actors, peddlers of medicines and herbs or aspirants to a military career. On the other hand, instruction was carried out either privately, hiring a teacher who resided in the home of a family whose children he instructed; or by sending the student, usually a child, as a servant to the teacher's house; supporting the teacher in a communal way —the case of Chan Heung—; or at fairs held in the villages at harvest time.

A few decades later, this had begun to change. Chan Heung's students were among the first to establish public commercial schools in the province of Canton (Guǎngdōng 廣東), meaning that they taught anyone who paid their fee. This trend had begun shortly before in the province of Fújiàn 福建, and from there it spread to neighboring Guǎngdōng before the rest of China. The Hung Sing school in Fóshān was one of the most successful in this regard.

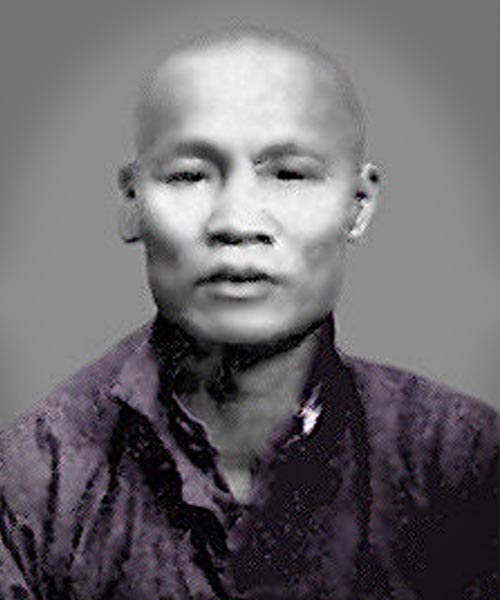

Chan Ngau Sing

Professionally, Ngau Sing was engaged in the copper industry as a blacksmith. A native of Fóshān, he had studied Hung Kyun 洪拳 in his youth and had the physical strength of an ox. When his teacher of Hung Kyun left Fóshān, he sent Ngau Sing to the Hung Sing 鴻勝 school to learn Choy Li Fut. It is said that Chan Ngau Sing was not very convinced of the effectiveness of Choy Li Fut and that he decided to test it by challenging Cheong Jim to a fight. Cheong Jim was victorious in all three rounds of the fight and Chan Ngau Sing was very impressed. Under Cheong's guidance, Jim learned quickly and eventually became an instructor at the school.

Chan Ngau Sing 陳吽盛.

Upon Cheong Jim's death, Ngau Sing succeeded him in charge of the Hung Sing school, while other students left to open new schools elsewhere in the region. The Fóshān school went through a period of decline, but Ngau Sing soon managed to revive the interest in Choy Li Fut and Lion Dance (wǔshī 舞獅), for which he was known as one of the "Three Kings of Lion Dance of Canton"—the other two being Chan Choeng-Mou 陳長毛 and Wong Feihung 黃飛鴻.

Under his leadership, the organization grew and opened new schools throughout the city. By 1920, at the height of its popularity, the association had thirteen branches and about three thousand members in Fóshān alone. According to estimates, this means that four percent of all male workers under the age of forty were linked in one way or another with the Hung Sing association.

The key to success

The timing of Chan Ngau Sing's assumption of charge of the organization coincides with a period of social change. Development and industrialization had left many workers unemployed, and urban violence by secret societies became a problem for the working class. After China's defeats in the still recent Opium Wars and the sanctions imposed by the West, the fear that the Western powers would divide up the country was growing. With it, discontent with the Manchu government also grew, and nationalism was taking hold among the local population.

If the Hung Sing school was successful, it was largely because of what it brought to its members, beyond mere martial arts instruction. The association was able to attract the modern urban workers of the industry. For them, it not only provided self-defence skills with which to defend themselves from aggression, but also membership of a large network of mutual support, useful in the search for employment or in the provision of other services, such as the maintenance of their own cemetery, which was an important charitable project for the time.

These prospects were particularly attractive to workers from other rural areas, who were far from their places of origin and lacked traditional support networks, such as clan associations.

On the other hand, Chan Ngau Sing established that new students had to be recommended by someone who was already a member, and applied a "three-exclusion policy", whereby he did not accept high government officials, local thugs or anyone who did not have a legitimate job.

Of these three exclusions, the last two ensured that the new students were not members of secret societies and, also, that they could pay the tuition fee – although it was not high. This policy maintained a select image for the school and sought to attract a specific clientele—the working class—while offering little inconvenience, as excluded groups rarely sought martial arts instruction.

Thus, the majority of members were workers from factories or small local shops.

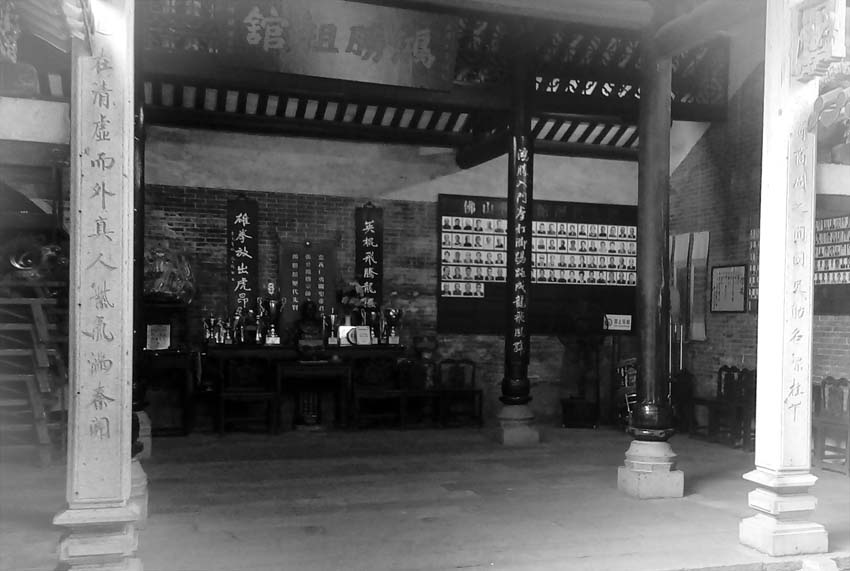

The Hung Sing school, nowadays.

The Hung Sing School in the Twentieth Century

The Hung Sing school flourished under Chan Ngau Sing. However, in a short time it would suffer new setbacks. The Boxer Rebellion (Yìhétuán yùndòng 義和團運動) was a major blow to traditional Chinese martial arts in general, as it greatly undermined the credibility of these systems. The governor of Guǎngzhōu 廣州 restricted martial arts to prevent the rise of Boxer imitators and thus further provocations to the West, and the government officially closed the Hung Sing school in 1900.

The Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) was an uprising led by a secret society known as Yìhétuán 義和團 ('Just and Harmonious Fists'). The Boxers, the name by which they were known in the West, were characterized by the practice of martial arts and esoteric rites based on mystical beliefs. Their fighters believed that these rites made them invulnerable to physical and spiritual harm.

The group opposed foreign influence, and its attacks on Western Christian missionaries drew retaliation from several countries in an international coalition. Western troops inflicted a humiliating defeat on the Boxers and forced the government to accept harsh peace terms for China.

We have discussed these beliefs of invulnerability in our article Dāo Qiāng Bù Rù: The Rituals of Invulnerability in the Martial Arts.

After this episode, Chan Ngau Sing left for Hong Kong 香港, where he tried to make a living as a vegetable vendor but, in an altercation with a policeman, he was arrested and deported back to Guǎngdōng.

It is unclear at what point the Hung Sing school reopened after the Boxer Rebellion, but other martial arts schools and associations, which had suffered the same fate, did so between the years 1903 and 1905, so we can assume that it would be at a near date. The era that followed was marked by the school's involvement in the revolutionary political movements of the time—here, finally, we do see a real and historical involvement in anti-Qīng 清 movements.

Sun Yat-Sen 孫逸仙, currently considered the "father of the nation", took advantage of rumours that the Manchus were going to sell China to Western powers. With the funding of various overseas Chinese associations, he founded a number of revolutionary organizations and relied on the already existing secret societies to start an anti-government movement.

Written records indicate that several leaders and members of the Hung Sing association, which in the first decade of the 20th century suffered increasing radicalization, participated in Sun Yat-Sen's revolutionary alliance, which culminated in the 1911 uprising.

This force was supported by the same demographic groups that were part of Hung Sing: industrial workers and small business owners. On November 10, 1911, a leader of the association named Lǐ Sū 李蘇 led his followers against the government troops stationed in Fóshān.

The Revolution of 1911, known as the Xīnhài Revolution (Xīnhài Gémìng 辛亥革命), forced the abdication of the last Manchu emperor, Pǔyí 溥儀, and gave birth to the Republic of China. This revolution not only ended the Qīng dynasty but an entire imperial era of more than two thousand years.

In the turbulent years that followed, new forces contended for power, and the Hung Sing School became involved in the activities of the Chinese Communist Party, founded in 1921. The following year the party established a working group in Fóshān that included two members of the Hung Sing association: Chin Wai-Fong 钱维方 and Loeng Gwai-Wa 梁桂華. The association shared the party's interest in workers' rights and collective negociations, and served as a recruiting niche in the struggle against capitalist business owners and landlords.

Among the photos of the school's former teachers, Loeng Gwai-Wa 梁桂華 and Chin Wai-Fong 钱维方 can be seen in second and third place, in the upper row, behind Chan Ngau Sing 陳吽盛.

The Hung Sing school was not the only one to get involved in the political movements of the time. Other martial arts schools supported the opposing side, Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang (Guómíndǎng 國民黨), and there were regular clashes between the schools of both sides.

In 1927, Chiang Kai-shek relied on secret societies to deal a blow to the communists. These events unleashed the famous massacre of Shànghǎi 上海 in April of the same year and a series of clashes that ended in the communist defeat.

In the years that followed, the Kuomintang attacked and dismantled the communist cells and institutions in Fóshān. The Hung Sing school was again closed and many of its most important members such as Chin Wai-Fong were forced to flee to Hong Kong and other places in Southeast Asia.

In 1936 and 1937, the Communist Party and the Kuomintang joined forces to confront the Japanese invasion of China. Chin Wai-Fong, returning from exile, trained anti-Japanese militias in the use of the dàdāo 大刀, a two-handed sabre that has since become known as the anti-Japanese sabre (抗日刀 kàngrì dāo).

During the war, the leaders of the Hung Sing association suffered a series of setbacks and many were again forced to flee. The association ceased to exist as it had until then. This chain of events marks the beginning of the decline in popularity of the Choy Li Fut style in Guǎngdōng Province. Although it never disappeared, and the school reopened in recent years, the style did not regain its former glory.

In the second half of the 20th century, martial arts fiction literature restored the fame of the Hung Sing school and immortalized it in novels and serialized stories.

Conclusions

The Hung Sing association was a commercial public school, like many others that began to emerge in the second half of the nineteenth century. Its success was due to the fact that it transcended mere martial arts training, and served as a network of mutual support for the working class of the time.

Under Chan Ngau Sing, the school spread by opening various associated branches and reaching several thousand members in the city of Fóshān.

In the early years of the 20th century, the school became involved in the Xīnhài Revolution of 1911, which would eventually overthrow the Qīng dynasty, and later in the activities of the Communist Party.

The Chinese Civil War and the Japanese invasion, in the context of World War II, caused a severe setback to the association, which was closed on several occasions by the Kuomintang before the Communist Party definitively took power in 1949.

The school later reopened, but Choy Li Fut would never regain the popularity it had enjoyed before the war.

Despite the school's revolutionary activities in the 20th century, it never participated as an institution in previous rebellions, such as the Tàipíng 太平天國, as many current practitioners believe. The mythology that links Choy Li Fut with the Tàipíng Rebellion expresses the ideals of the practitioners of the time of the Xīnhài revolution, and not those of those early practitioners in the nineteenth century.

It was martial arts fiction literature of the second half of the 20th century that propagated this mistaken belief. This literature immortalized the school's fame, but it also replaced some of its real history with mythical inventions, in the minds of many people.

Sources:

Benjamin N. Judkins, Jon Nielson. The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. University of New York Press, 2015