When we think of Chinese martial arts, a great technical and stylistic diversity comes to mind: Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛, Hung Ga Kuen 洪家拳, White Crane (白鶴拳 Báihèquán), Tàijíquán 太極拳, Wing Chun 詠春, Xíngyìquán 形意拳, Drunken Boxing (醉拳 Zuìquán), Tánglángquán 螳螂拳, to name just a few that come to mind.

However, Chinese martial arts have not been classified into styles other than by a relatively small part of its history. In addition, this stylistic diversification seems to have its origin in the performing arts.

Introduction:

In the Míng 明 dynasty (1368-1644) we already have evidence of the existence of a wide variety of martial arts styles, as evidenced by texts such as the manuals of the famous general Qī Jìguāng 戚繼光, of which we have spoken on other occasions. Before this time Chinese martial arts were not grouped under different names. Students learned from a certain teacher, sometimes associated with a locality, and defined themselves in terms of lineage associated with an often mythical founder. This grouping under lineages began in the Sòng 宋 dynasty.

Until the advent of modern weaponry, only the basic use of infantry and cavalry weapons was taught in military martial arts. Military training thus focused on a small technical repertoire for a small number of weapons —those that were regulatory. That is, only the simplest and most effective techniques were trained, in order to apply them against an opponent with speed, precision and power.

Moreover, large numbers of students needed to be trained simultaneously, to fight as a unit and not as isolated individuals.

In this way, and because some units of the army had to be integrated with other units in the campaign (and because all fought in the same way), their martial arts would have been homogeneous throughout the territory. It is true that some skills were used more frequently in some areas than in others, such as horseback fighting in regions bordering with nomadic peoples, but the way of fighting was the same in all of them.

The entertainment districts of the Song Dynasty:

In the Sòng 宋 dynasty a number of entertainment districts appeared where shows and amusement events were organized; there, outside the military sphere, martial shows of mainly aesthetic pretensions began to develop. It is precisely in these entertainment quarters where the first family styles and lineages of martial arts are recorded.

Authors such as Lín Bóyuán1 林伯原 defend this idea that different martial arts schools developed in the entertainment quarters in the Sòng era. According to this author, the articulation of separate schools occurred at the end of the dynasty, after the fall of northern China to the jurchen (女真 nǚzhēn). At the beginning of the Sòng dynasty, the martial arts of the army spread and were taught to the peasant population, and subsequently these same arts evolved in the entertainment quarters.

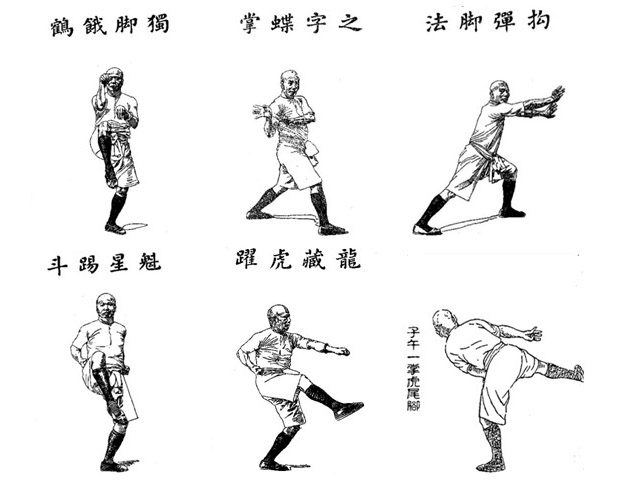

More variety was needed on the stage than on the battlefield. Exhibitions of martial arts as entertainment led to the elaboration and dramatization of these arts, mainly interested in aesthetics, which gradually produced a clear differentiation between different practitioners. These differences were linked to lineages of practice.

This coincided with the development of theatre and merged with oral traditions. Martial artists were romanticized for their ability to challenge authority in an unjust world. Martial arts empowered the individual in the face of large power structures, at least in popular fiction. Some of these articulations emerged in early stories of the bandit Sòng Jiāng 宋江, first put in written form around 1300, probably from oral stories already in circulation2.

These martial arts were passed down and over time particular systems were developed, each with its own characteristic technical repertoire, which gave rise to schools or styles named for their actual or imagined origins.

Later evolution:

At this time, however, style names were not yet registered. If we go to the classic Chinese novel Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn 水滸傳 (The Water Margin, also called Bandits of the Swamp), from the end of Sòng, we see that although its main characters have particular abilities, there is no mention of combat styles.

The first records of names of fighting styles already correspond to the Míng dynasty. At this time, several authors, including the aforementioned Qī Jìguāng, compiled lists of martial styles in an attempt to find the most effective and functional skills of the time. Qī lamented that many of these styles lacked a complete technical repertoire.

Most of these authors, expert men-at-arms, were also disappointed with what they called "flowery styles" (花拳 huā quán), excessively elaborated, which were pleasing to the eye but nonetheless ineffective.

By this time, these "flowery" styles had already lost the essence of fighting and were moving away from their original effectiveness. Despite this, and despite the variety of styles throughout the territory, it seems that a core of effective techniques still existed.

Conclusions:

Martial arts styles or lineages seem to have their origin in exhibition martial arts. We must not, however, draw the conclusion that the styles practiced today necessarily derive from these entertainment styles. It is simply the beginning of a stylistic differentiation and the custom of tracing lineages grouped around these differences.

Of course, after the Sòng dynasty, when this practice appeared, new styles would originate, derived from the military arts and therefore based on effectiveness and not on aesthetics.

Despite this, even these most effective styles will try to differentiate themselves from each other by elaborating their techniques, and we can assume that they were equally influenced by the entertainment styles despite maintaining martiality.

Notes:

- Cited in Peter A. Lorge, Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 134.

- íd. p. 138.