Introduction

Acupuncture occupies a preeminent place among the healing arts of China and the rest of Asia. Its age is subject to debate. Some have intended to see in the biānshí 砭石 (polished and sharp stone needles) the proof that acupuncture was already practiced in Neolithic times.

But primitive methods of puncture with stones are not synonymous with acupuncture, since the last is based on a theoretical corpus that describes the circulation of internal energy (qì 氣) through channels and meridians (jīng luò 經络) and puncture at specific points (shùxué 俞穴), a theoretical corpus that would not be developed until much later.

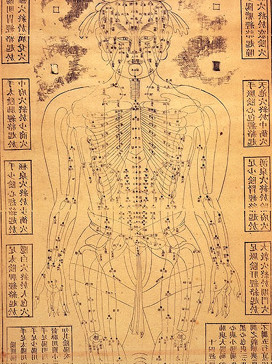

Representation of energy vessels and channels (jīng luò 經络).

From stone puncture to acupuncture

There is archaeological evidence of the use of certain polished and sharp stone needles, called biānshí 砭石, for the treatment of diseases and ailments. Numerous biānshi have been unearthed dating back to the Neolithic period, which in China developed between 10,000 and 2,000 BC. Bone needles between three and four thousand years old have also been found.

Written evidence of the use of this type of puncture with stones dates back to the fifth to third centuries BC. Also in the Mǎwángduī 馬王堆 texts, and in the Huángdì nèi jīng 黃帝內經 (Canon of Internal Medicine of the Yellow Emperor), both from the second to first century BC, there are descriptions of the use of biānshi.

However, the use of stones as needles to treat ailments cannot be considered acupuncture, since we do not have evidence that these methods were based on the same principles.

In the tombs of Mǎwángduī, dating from 168 BC, the medical texts found show a theory of meridians not yet fully developed; in addition, there is no mention of specific acupuncture points.

The first document that undoubtedly reflects the use of acupuncture as a system of diagnosis and treatment is the Yellow Emperor's Canon of Internal Medicine (ca. 100 BC). This text shows a continuity of ideas with respect to the Mǎwángduī texts, and a theory of meridians and points already fully developed.

The Canon of Internal Medicine describes puncture methods as well as specific points, and the energy meridian system is already established in its current form. Based on this evidence, it is commonly accepted that the origin of acupuncture dates back to the Hàn 漢 era.

In the following centuries acupuncture would be established as one of the main therapies in China, alongside herbal medicine, massage and moxibustion.

The basis of acupuncture

Acupuncture is based on the insertion of needles at certain points with the intention of altering the circulation of internal energy through the meridians and energy channels to restore health.

However, in the old days it was believed that blood circulated through the channels together with qì, so some authors (Epler) have related the origin of acupuncture with bloodletting, a procedure by which blood was extravasated from the patient by various mechanisms, with the aim of eliminating pathogens. Ancient Chinese doctors would have observed, according to this theory, a beneficial effect of puncture even when blood did not flow out, and related this effect to an expression of internal energy or qì.

The Mǎwángduī texts, in which reference was found to the energy channels, as well as to the techniques of bloodletting and cauterization, but not to acupuncture, would show a stage prior to puncture without bleeding in specific points, to which the Huángdì nèi jīng already refers.

On the other hand, it has long been thought that this theory of points and channels is not based on anatomy. One of the reasons is that the energy channels do not have a physical correlate in the body. Another reason is that the ancient ban on dissection of corpses would have prevented anatomical research of the human being.

Since the Hàn dynasty, there are no records of dissections in China until almost a millennium later. In the Sòng 宋 dynasty, dissections were performed again after the execution of criminals, and then dissections were not heard from again until the nineteenth century, when Westerners, noting that Chinese medicine did not practice them, reintroduced them.

However, recent studies have shown the relationship between anatomical structures and the acupuncture point nomenclature system. V. Shaw has studied this nomenclature from a linguistic, cultural and historical point of view, as well as the change it has undergone over time. Shaw points out that it was precisely during the Sòng dynasty (when dissections were practiced) when the first "bronze men" (銅人 tóng rén) appeared, life-size human-shaped bronze figures on which a map of acupuncture channels and points was represented, with the aim of teaching and examining medical students.

Bronze man (銅人 tóng rén) for the study of acupuncture points.

These figures were hollow and had small holes in the acupuncture points. These holes were covered with wax, and the entire figure was filled with water. The student had to insert the needle at the exact point, so that when pierced the wax water flowed out.

We find it interesting to cite here some of the results of Shaw's research:

- some components designate anatomical positions: 天 tiān, "higher"; 下 xià, "lower";

- reflect form and/or function: 髎 liáo, "fossa", "foramen" or "depression";

- indicate unusual structures: 飛 fēi indicates a single nerve separating from a bundle;

- describe the physical appearance of a deep structure by comparison with an everyday object: 谿 xī, "brook", indicates a vascular structure in a cleft, or 絲 sī, "silk", appears to be related to fascia.

As it is clear, there is a correlation between certain names of acupuncture points with specific anatomical features. For Shaw, this reinforces the hypothesis that acupuncture is based on anatomical research of the human being, and raises interesting questions: if acupuncture is based on anatomical research, is it possible that qì (internal energy) also has some anatomical basis?

Although the mechanisms by which acupuncture takes effect are not known to science today, studies are being carried out that investigate a possible relationship of the energy meridian system with the system of fascias and interstitial connective tissue (Langevin & Yandow, 2002), as well as the relationship between the idea of qì and the processes that occur in these tissues.

There are more and more studies in this regard, and it is possible that one day not too far western science may find an explanation for the functioning of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Sources:

Kan-Wen Ma, Acupuncture: Its Place in the History of Chinese Medicine

Shaw, V., & Mclennan, A. K. (2016). Was acupuncture developed by Han Dynasty Chinese anatomists? Anatomical record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology , 299(5), 643-59.

Shaw, V., Diogo, R., & Winder, I. C. (2020). Hiding in Plain Sight-Ancient Chinese Anatomy. Anatomical record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology.

White, Adrian & Ernst, Edzard. (2004). A brief history of acupuncture. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 43. 662-3. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg005.

Langevin, H. M., & Yandow, J. A. (2002). Relationship of acupuncture points and meridians to connective tissue planes. The Anatomical record, 269(6), 257–265.