Introduction

During the Qīng 清 dynasty (1636-1912) there were groups of martial artists who believed in obtaining, through certain esoteric rituals and practices, a protection that made them invulnerable to both physical and spiritual damage. This invulnerability was referred to as dāo qiāng bù rù 刀槍不入, literally, "sabres and spears do not penetrate".

These beliefs and rites originated in the mystical and religious currents of Buddhism and Taoism, and were part of the superstitions prevalent in rural China at the time, and yet survived even the fall of the last Chinese dynasty, in a world that was beginning to industrialize.

Historical context: The problem of security

In the Qīng dynasty, banditry was a big problem in Chinese society, and looting by bandits was constant and frequent in rural society. Banditry itself was a reflection of other social problems, such as the exploitation and oppression of peasants. Generally, bandit groups were not professional groups dedicated exclusively to this task, but groups of peasants who occasionally pillaged to survive.

Although in recent times this phenomenon has been looked at through a prism of romanticism that presented these groups as defenders of justice and fighters against a corrupt system, inspired by novels such as the Water Margin (Shuǐhǔ zhuàn 水滸傳), the truth is that they were dedicated to predatory violence, and did not fight for the defense of their values but for the obtaining of resources.

To protect themselves from these bandits, martial arts groups or societies were formed, some linked to secret societies or religious groups. These groups ended up using violence in similar ways, contending with each other for resources such as water sources, grazing land or farmland, and noted for the use of rituals of invulnerability that supposedly conferred protection from weapons.

Martial arts societies

The groups of martial artists that were formed to protect the localities from bandits were formed around wandering teachers who traveled from locality to locality, teaching martial arts along with the aforementioned protection rituals.

In principle, these groups were formed with the purpose of providing protection against looters. Their leaders were wandering masters who depended on their martial skills to earn their livelihood. But, as soon as these societies gained some power, they began to get involved in local conflicts (xièdòu 械鬥) between clans fighting for local resources. These groups ended up becoming a destabilizing factor and threatening the security of rural communities.

Xièdòu (inter-clan armed violence, short for chíxiè xiāngdòu 持械相鬥) and martial societies fed each other. Warring clans needed martial societies to increase their power, and the leaders of these societies needed local conflicts to build their reputation.

The xièdòu evidenced the weakness of the central government, whose local officials avoided intervening in these disputes or even reporting them to their superiors, and who often collected bribes from the clans involved for staying out of it.

Martial societies contending in rural areas in this period were characterized by the use of protective rituals, which invoked the presence of martial deities and were able to subdue demonic powers. These rites consisted of the recitation of sacred texts, the use and ingestion of talismans and amulets and the obedience of a series of precepts.

Among the organizations that used these methods is the Great Sabre Society (Dàdāohuì 大刀會), known for its "golden bell armour" (jīnzhōng zhào 金鐘罩), a technique of invulnerability that made the practitioner's body impenetrable to weapons. This society operated in the late nineteenth century in the border region between Shāndōng 山東 and Jiāngsū 江蘇 and was tolerated by the authorities, as it organized armed forces of defense against bandits. From this society later emanated others, such as the Red Spear Society (Hóngqiānghuì 紅槍會), which adopted similar rituals.

The best known case in which this type of rituals were used was during the Boxer Rebellion (Yìhétuán Yùndòng 義和團運動), initiated by a group that rose up against foreign presence in the late nineteenth century. The Boxers used various forms of invulnerability rituals, including the aforementioned "golden bell armour" and the "iron shirt" (tiě shān 鐵衫). Its members, convinced of their invulnerability, suffered great carnage at the hands of Western troops, who ended up looting Beijing.

Members of the Boxers (Yìhétuán Yùndòng 義和團運動).

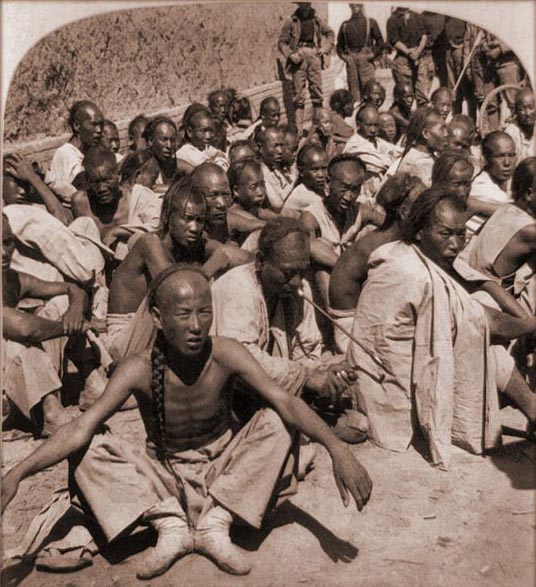

Boxer fighters captured by Western forces.

Despite the great humiliation that China suffered in this episode, after the Boxer Rebellion, martial societies continued to form under the same beliefs of invulnerability, such as the Yellow Crane Society (Huánghèhuì 黃鶴會). A legend tells of the formation of this group in 1934 when a traveler from Ānhuī 安徽 arrived in the district of Póyáng 鄱陽 in Jiāngxī 江西 claiming to know the rituals of invulnerability. When the locals tried to cut him with a sabre without hurting him, many peasants wanted to learn his techniques, and so the Yellow Crane Society was formed.

There was also a martial society formed by women, the Flower Basket Society (Huālánhuì 花籃會). Its members carried baskets of flowers with magical powers that they used as shields and protected them from enemy weapons, even firearms.

Generally, these societies were formed when a certain clan invited a martial artist to open a worship or training hall (táng 堂) in the locality.

The beliefs behind the rituals of invulnerability

The roots of the belief in the efficacy of these esoteric rituals lie in the popular culture of the time. In the popular imagination was rooted the belief in demonic forces capable of causing harm to human beings. These forces were kept at bay by the worship of protective tutelary deities.

However, many people associated the danger posed by real enemies with these demonic forces. Therefore, to combat these enemies, not only physical means were necessary, but also esoteric means, such as the invocation of powers capable of subduing them.

This spiritual warfare required strict morals on the part of each participant, in addition to a complex system that included the recitation of spells, spiritual possession, or the possession of amulets or special objects. If the requirements were not strictly met, the effectiveness of the rites was lost and consequently fatal injuries could be suffered.

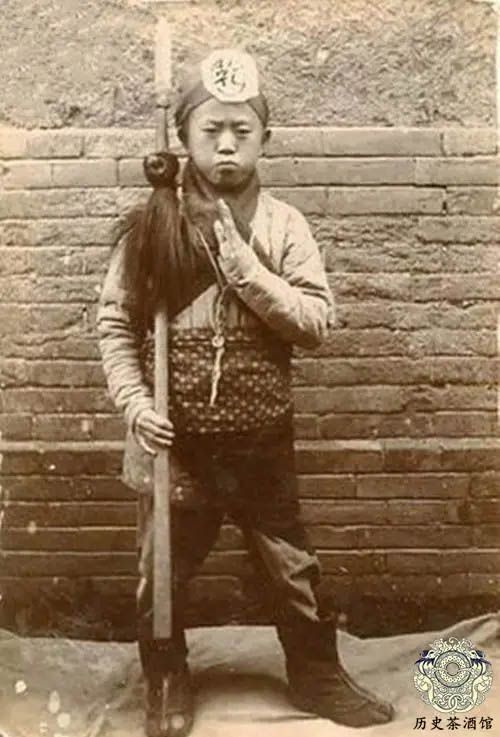

Young member of a martial society carrying a spear and a magic talisman on his head.

The rites of invulnerability

The rites practiced to achieve invulnerability varied between groups, although they had common characteristics.

They usually began with an initiation ceremony in which the practitioner entrusted himself to a popular deity, such as Xuán Wǔ玄武, Guān Yīn 觀音 or Guān Gōng 關公; some groups attributed their supposed invulnerability to possession by these deities. He also had to swear loyalty to the leader of the society, perform the kowtow (kòutóu 叩頭) and agree to follow a series of rules of conduct.

Image of the martial deity Xuán Wǔ 玄武.

The Yellow Crane Society required a time of forty-nine days for learning, during which students sat in meditation three times a day, lit incense and burned yellow papers, or recited scriptures and spells.

On the other hand, in the Great Sabre Society a time of ten nights sufficed, in which large stones were placed on the belly of the students and they were cut with swords. Apprentices were also trained in the use of the sabre.

In battle, members of these groups recited different spells, which varied depending on the circumstances. To convey the magic formulas to the students, yellow papers with the spells were fastened to their skin and again they were cut with swords.

The Red Spear Society could take anywhere from a few weeks to several months to train its students. Incense and prayers were offered and the teacher bestowed on the student a spell and a talisman written on paper, which was burned and whose ashes were ingested by the initiate.

The training of these groups included breaking bricks on the head of the practitioner, without him being able to show pain, or the practice of cuts with weapons on his skin; only students whose resulting injuries were minimal were fit to continue learning.

Some were even subjected to artillery fire, although it seems that only inefficient old weaponry was used. Even so, most survived the training.

In addition to all this, learning also included conventional martial arts training in preparation for spear and sabre combat.

The failure of invulnerability rites discredited martial societies. However, the effectiveness of rituals was subject to so many taboos that it was not difficult to justify their failure. These taboos had to do as much with the practitioner's actions, diet, and sexual behaviour as they did with the practitioner's thoughts. So when the magic of invulnerability failed, it was attributed to the violation of one of these taboos.

In 1949, when the martial societies in Póyáng could not cope with the People's Liberation Army with their modern weaponry, many societies disintegrated. On another occasion, a Red Spear Society teacher was beaten to death by a group of people after ten of his students died during their training.

Origin of these practices

The invulnerability techniques used by martial societies appeared in the region of Shāndōng and Hénán 河南 during the nineteenth century. However, they were not exclusive to these groups. Other groups also made use of similar demonstrations, such as street vendors of medicinal formulas, who tested the effectiveness of their wares by submitting to blows and cuts.

These beliefs were widespread, although they were not accepted by all martial artists and were not considered part of orthodox practice. The martial arts fiction novels that circulated at the time helped to create this collective imaginary in which practices of this type had a place, and tried to link them to theories of Chinese Medicine related to qì 氣 or vital energy.

Some scholars see the origin of invulnerability practices in ancient dǎoyǐn 導引, a system of Taoist energy practices. Meir Shahar relates them to the concept of "Diamond Body" (jīngāng shēn 金剛身), from Indian Tantric Buddhism, which invoked a barrier that protected the body from physical and spiritual harm.

Shahar also sees the Yìjīnjīng 易筋經, "Muscle/Tendon Change Classic", an esoteric text of the seventeenth century that greatly influenced later Chinese martial arts, as the probable link between the Indian tantric tradition and the martial arts of the Qīng era.

The value of invulnerability rites

The belief in the techniques of invulnerability is all the more surprising to us when it is happening at a time when China was beginning to industrialize. But we have to look for the value of these rites beyond the supposed effect that their learning promises, and their roots, beyond the mere superstition of the population. In fact, teachers who taught these practices were often invited to a locality by members of the social elite who did not practice the rites or did not believe in them.

The true value of rituals was therefore based on the psychological factor. The practice of protection rituals boosted the morale of fighting units and provided cohesion to local communities in the face of dangers from outside. In addition, it favoured the organization of its members and maintained discipline, creating a group identity capable of guaranteeing unity in a community with divided interests.

This psychological factor was decisive in the union of different martial societies during the aforementioned Boxer Rebellion. However, the resounding failure of this rebellion would also play a decisive role in the end of esoteric practices.

Fighter with a banner of the Boxer Movement (Yìhétuán Yùndòng 義和團運動).

Conclusions

The Boxer Rebellion was a terrible humiliation for the Chinese nation, and made the country's martial arts appear obsolete and retrograde. If these arts were to be saved, they had to be stripped of this backward esotericism. However, the practices of invulnerability survived for a while during the Republican era (1912-1949).

But with the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, rural areas were cleansed of bandits and the roots that sustained the existence of martial societies were destroyed. The rituals of invulnerability ended up disappearing.

Despite having existed during the late Qīng era and during the Republican era, these practices never formed more than a minor current in Chinese martial arts, and were not seen as orthodox by other martial artists who did not practice them.

Despite having disappeared, we find vestiges of these practices in the current hard Qìgōng 氣功 that is practiced in some martial arts schools. These schools practice techniques such as the "Iron Shirt", reminiscent of those practiced by ancient martial societies.

Sources:

Rural Wandering Martial Arts Networks and Invulnerability Rituals in Modern China, Yupeng Jiao, 2020. Martial Arts Studies 10, 40-50.

Rituals of the Red Spear Movement: Invulnerability, Spirit Possession and Battle Magic, Ben Judkins. Kung Fu Tea.

Cambridge Illustrated History China, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, 1996.

Diamond Body: The Origins of Invulnerability in the Chinese Martial Arts, Meir Shahar. Vivienne Lo, ed., Perfect Bodies: Sports Medicine and Immortality. London: British Museum, 2012.