Introduction:

The Chá Jiǔ Lùn 茶酒論 (Discourse of Tea and Wine) is a satirical text of the Táng 唐 dynasty, which represents a dialogue between the personified substances of tea, on the one hand, and wine (or also, liqueur or alcohol), on the other. This text is not only interesting because it gives us information about the customs and mentality of the time, and the ideas associated with these two beverages, but it is also a metaphor that represents a discussion between philosophical or spiritual currents.

Historical context:

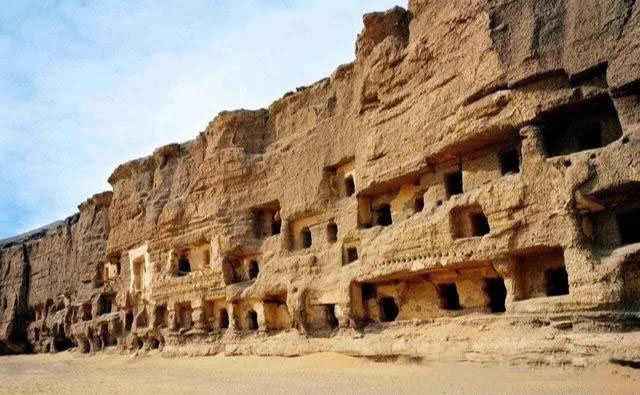

The Chá Jiǔ Lùn was discovered in the twentieth century in the Mògāo 莫高 caves, in Dūnhuáng 敦煌. Dūnhuáng was an especially important enclave on the Silk Road, a place of confluence of different cultures. There was an important Buddhist community there. The Mògāo Caves are a set of more than 500 grottoes dug into the sandstone cliffs, which served as temples and places of worship.

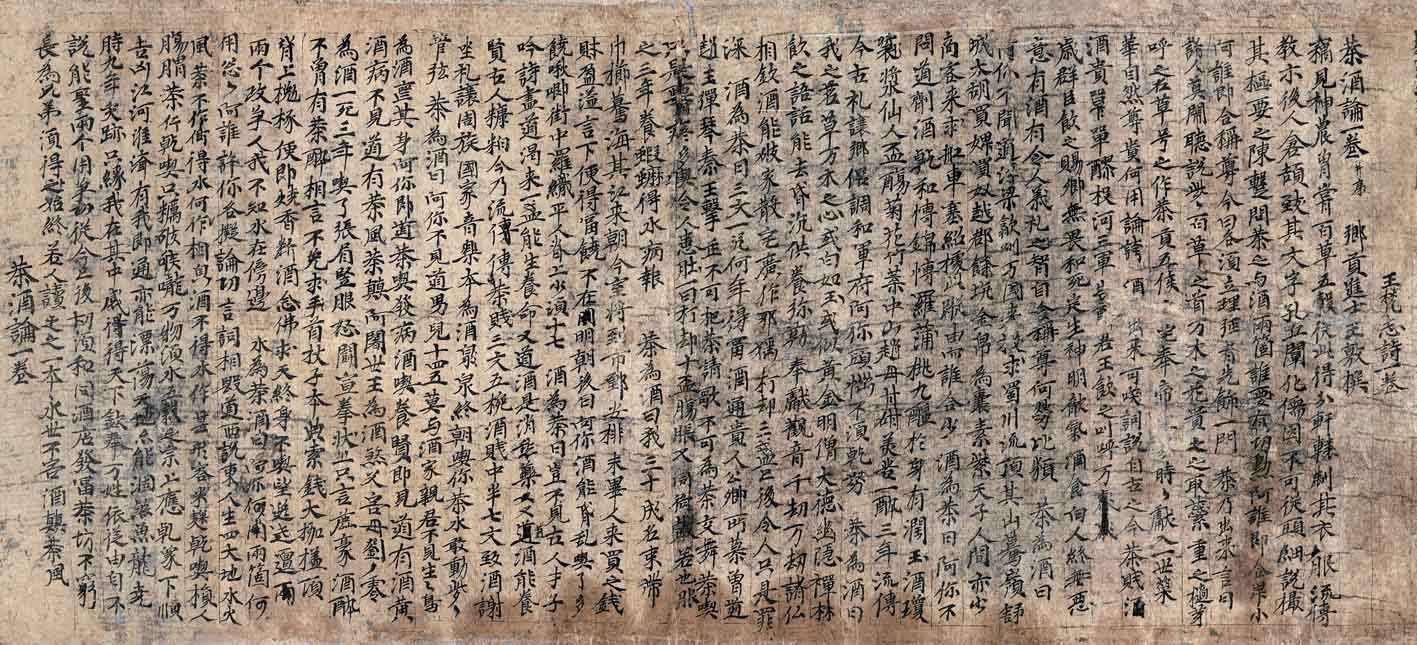

In one of the caves was discovered, at the beginning of the twentieth century, a large library of ancient texts, which had remained sealed and hidden since the eleventh century. Among these manuscripts were six copies of the Chá Jiǔ Lùn, which allows us to infer that this was a popular text in the Dūnhuáng community.

The exact date of the Chá Jiǔ Lùn is unknown, but it is believed to date from the mid-seventh to the tenth centuries, after tea became a prodcut of daily consumption. Its author, Wáng Fū 王敷, is known only to have been a Confucian scholar.

Mògāo 莫高 caves.

Characteristics of the Cha Jiu Lun:

The Chá Jiǔ Lùn is one of Dūnhuáng's most sophisticated texts in terms of style and language. However, the text contains numerous scribal errors, with many characters mistaken by other homophones. As pointed out by Amy Pearse (2018), who has analyzed several aspects of the Chá Jiǔ Lùn, these errors are typical of oratory texts as they have been put in writing. In addition, some of the fragments of the text contain annotations indicating scene guidelines, suggesting that the text was used as a representation, and perhaps originally written for the purpose of being represented on a stage.

Most of the text is structured in lines of four or six characters, with lines of five or eight characters interspersed throughout the text, which produces changes of pace that suggest the excitement of the debate. The text is rhymed for the most part, although the rhyme does not follow a uniform structure throughout the text.

In the text, tea and wine, personified, carry a heated dialogical confrontation defending each their virtues and attacking the other, with the appearance of a third character at the end that puts order between them. In their speech, the customs and symbolic functions of one and the other in society can be seen. Tea defends itself from a position similar to that of the Buddhists in its precept against the intake of alcohol, making use of arguments of that nature.

The Chá Jiǔ Lùn has been seen as a purely Buddhist text, due to the terminology used by the character of tea in its argumentation. However, Pearse, in her analysis, understands it as a symbolic representation of the interreligious debates in the imperial court, between the three religions. The inclusion of the term lùn 論 (speech, debate, treatise) in the title would also conform to this interpretation.

Text and commentary of the Cha Jiu Lun:

We have not found a complete translation of this text, neither in English nor in Spanish, but we will try to offer an approximate translation of the text, relying on the partial translation of James A. Benn (2015) and trying to complete it ourselves. We have left the original text in Chinese so that anyone who has knowledge of the language can read it in its original form and, in advance, we apologize for any errors or omissions that our translation may contain.

We will section the text into parts, and for each part, we will offer the original text in traditional Chinese, the transliteration in the pīnyīn 拼音 system, where you can appreciate the rhyme, a translation and, finally, an explanatory commentary.

To differentiate the substances of tea and wine from their incarnation into characters in the text, we will write the name of these characters in capital letters.

1

茶酒論﹝唐﹞王敷撰

Chá jiǔ lùn ﹝ Táng ﹞ Wáng Fū zhuàn

Discourse of Tea and Wine (Táng Dynasty), by Wáng Fū

2

竊見神農曾嘗百草,五谷從此得分﹔

qiè jiàn shén nóng zēng cháng bǎi cǎo, wǔ gǔ cóng cǐ dé fēn;

軒轅制其衣服,流傳教示后人。

xuān yuán zhì qí yī fú, liú chuán jiào shì hòu rén.

倉頡致其文字,孔丘闡化儒倫。

cāng jié zhì qí wén zì, kǒng qiū chǎn huà rú lún.

不可從頭細說,撮其樞要之陳。

bù kě cóng tóu xì shuō, cuō qí shū yào zhī chén

暫問茶之與酒,兩個誰有功勛?

zàn wèn chá zhī yǔ jiǔ, liǎng gè shuí yǒu gōng xūn?

阿誰即合卑小,阿誰即合稱尊?

ā shuí jí hé bēi xiǎo, ā shuí jí hé chēng zūn?

今日各須立理,強者光飾一門。

jīn rì gè xū lì lǐ, qiáng zhě guāng shì yī mén.

Translation:

Shénnóng came to know every type of plants and the five cereals; Xuān Yuán invented clothing. Cāng Jié invented writing, and Confucius explained Confucianism. But let's not mince words and get to the point. For a moment, let's ask Tea and Wine, who has made merit contributions? Which of the two is the most respected? Today, each of them will present their arguments to clarify this question.

Commentary:

This first part is a preface in which the author introduces the achievements of legendary figures and cultural heroes who brought civilization.

Shénnóng 神農 is a figure linked to medicine, who is credited with the invention of agriculture. In mythology, Shénnóng taught mankind to sow and harvest grain. It is believed that he had tasted all types of plants to know which were safe for human consumption and which were not. In addition, he is credited with the discovery of tea. It is believed that Lù Yǔ 陸羽 (733-804), writer of the first extant book on tea, was the creator of this myth of Shénnóng as the discoverer and patron saint of tea, a myth that would be very present in the popular imagination during the rest of China's history.

Painting illustrating Shénnóng 神農 testing different plants.

Other legendary heroes are then cited, such as Xuān Yuán 軒轅 (the Yellow Emperor, 黃帝 Huángdì), who, among other achievements, is credited with inventing clothing; and Cāng Jié 倉頡, scribe of the Yellow Emperor and inventor of writing. Finally, Confucius (Kǒngzǐ孔子, cited here as Kǒngqiū 孔丘), is mentioned, whose doctrine governed the organization and ritual of both state and family life.

This preface introduces the subject of discussion in the same way that religious debates were introduced in the imperial court.

3

茶乃出來言曰:

chá nǎi chū lái yán yuē:

諸人莫鬧,聽說些些。

zhū rén mò nào, tīng shuō xiē xiē.

百草之首,萬木之花,

bǎi cǎo zhī shǒu, wàn mù zhī huā,

貴之取蕊,重之摘芽,

guì zhī qǔ ruǐ, zhòng zhī zhāi yá,

呼之茗草,號之作茶。

hū zhī míng cǎo, hào zhī zuò chá.

貢五侯宅,奉帝王家,

gòng wǔ hóu zhái, fèng dì wáng jiā,

時新獻入,一世榮華。

shí xīn xiàn rù, yī shì róng huá.

自然尊貴,何用論夸?

zì rán zūn guì, hé yòng lùn kuā?

Translation:

Tea came out, and said, "Everyone, be silent; listen to this. Among the hundred herbs, I am the first; among the ten thousand plants, I am the essence. I’m the harvest of the best buds. I am called mingcǎo, and also tea. I serve as a tribute to the five marquises, and as a gift to the imperial family. I offer them the latest trend, a whole flourishing life. I am honorable and respected, what need is there to exaggerate?"

Commentary:

Here, both "the hundred herbs" (百草 bǎi cǎo) and "the ten thousand plants" (萬木 wàn mù) refer to an infinite number of plant species. Thus, Tea begins by presenting itself as the first plant of the entire vegetal kingdom, and tells us that it is known as mingcǎo 茗草, in addition to as "tea", chá 茶.

Mingcǎo, or simply míng 茗, is one of the names by which tea was known before the Táng dynasty, when the word chá 茶 appeared, which derives from the term tú 荼, that did not designate a specific species but a series of bitter plants.

Illustration of the tea plant, camellia sinensis.

Tea ends its initial speech by alluding to the economic value it was acquiring at that time. Although tea was previously consumed locally, especially in southern China, it became popular during Táng, when it became a commercial product. Tea was commonly used as a gift by the Chinese social elite, including the court and the imperial family.

The "five marquises" (五侯 wǔ hóu) can refer to five official titles that were bestowed by the emperor in ancient times: gōng 公, hóu 侯, bó 伯, zǐ 子, nán 男, which we can translate as duke, marquis, count, viscount and baron, respectively, and representing the second rank of Chinese nobility. However, and by extension, it most likely refers here to the powerful and wealthy families of the nobility in general.

4

酒乃出來曰:可笑詞說!

jiǔ nǎi chū lái yuē: kě xiào cí shuō!

自古至今,茶賤酒貴。

zì gǔ zhì jīn, chá jiàn jiǔ guì.

單醪投河,三軍告醉。

dān láo tóu hé, sān jūn gào zuì.

君王飲之,賜卿無畏,

jūn wáng yǐn zhī, cì qīng wú wèi,

群臣飲之,呼叫萬歲。

qún chén yǐn zhī, hū jiào wàn suì.

和死定生,神明歆氣。

hé sǐ dìng shēng, shén míng xīn qì.

酒食向人,終無惡意,

jiǔ shí xiàng rén, zhōng wú è yì,

有酒有令,禮智仁義。

yǒu jiǔ yǒu líng, lǐ zhì rén yì.

自合稱尊,何勞比類!

zì hé chēng zūn, hé láo bǐ lèi!

Translation:

Then, Wine came out and said, "What a ridiculous speech! From ancient times until now, tea has been despised and wine valued. When a single glass of wine was poured into the river, the three armies got drunk. When the sovereign and ministers drink, it gives them courage. When the crowd drinks, they shout ‘long live the emperor’. I harmonize life and death, and the divinities admire the energy I confer. Wine has never brought any harm to human being. Where there is wine there is order, ceremony, wisdom and benevolence. I am both old and respectable."

Commentary:

The word jiǔ 酒 can be translated as "wine", but it also refers to all kinds of liqueur or alcoholic beverage. Therefore, the character who speaks now does so on behalf of all spirits.

Wine begins its discourse by mocking the words of its antagonist, and alluding to its antiquity as a drink. To support his speech, he alludes to a story from the Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋 Chūnqiū), according to which on one occasion the king of Yuè 越, campaigning against the state of Wú 吴, poured a cup of wine into the river and made his men drink from the waters. The entire army (the "three armies", 三軍 sān jūn, i.e. the armies of the left, right, and centre) got drunk and fought with great bravery.

In China, wine was used in court ceremonies and as an offering to the dead, and played an essential role as part of etiquette and in social relations. Thus, Wine is presented as a bearer of tradition and highlights its role in ritual, which in Confucianism was fundamental for the preservation of the order of the state. In addition, it alludes to the Confucian virtues of courtesy (禮 lǐ), wisdom (智 zhì), benevolence (仁 rén) and righteousness (義 yì), which are four of the five essential virtues of Confucianism.

Wine played an essential role in social relations.

5

茶謂酒曰:阿你不聞道:

chá wèi jiǔ yuē: ā nǐ bù wén dào:

浮梁歙州,萬國來求,

fú liáng shè zhōu, wàn guó lái qiú,

蜀山蒙頂,騎山驀嶺。

shǔ shān mēng dǐng, qí shān mò lǐng.

舒城太湖,買婢買奴。

shū chéng tài hú, mǎi bì mǎi nú.

越郡餘杭,金帛為囊。

yuè jùn yú háng, jīn bó wéi náng.

素紫天子,人間亦少,

sù zǐ tiān zǐ, rén jiān yì shǎo,

商客來求,舡車塞紹。

shāng kè lái qiú, chuán chē sāi shào.

據此蹤由,阿誰合小?

jù cǐ zōng yóu, ā shuí hé xiǎo?

Translation:

Tea replied to Wine: "Have you not heard the saying '[the tea of] Fúliáng and Shèzhōu, all nations come in search of it'? Crossing mountain ranges, [even] the Shǔ mountains. [The people of] Shūchéng and Tàihú [come to] buy me. The prefectures of Yuè and Yúháng are brimming with money and silk. Among ordinary people and emperors, there are few honours like this in the world. The merchants arrive seeking for [tea] and fill their boats and carts. For all these reasons, who do you think is big and who is small?"

Commentary:

Tea begins by quoting a saying of the time: 'the tea of Fúliáng and Shèzhōu, all nations come in search of it'. During the Táng Dynasty, the ancient city of Fúliáng 浮梁 was a large tea distribution centre, the most famous of the time. During the Sòng 宋 dynasty, the city was renamed Jǐngdézhèn 景德鎮, although the region retains the name Fúliáng.

Fúliáng 浮梁, current Jǐngdézhèn 景德鎮.

Tea continues his speech alluding to its value as a commodity, highlighting the hardships that the caravans of merchants went through to acquire it. The Shǔ 蜀 Mountains refer to the present-day Sìchuān 四川 province, a mountainous area of difficult transit. It was probably in this region, and in the adjacent Yúnnán 雲南, where tea grows wild, where the habit of drinking tea arised.

Before being grown for consumption and marketed as a product, already during Táng, tea was consumed locally in these regions, harvested directly from bushes and wild trees. This was a product not prepared for transport, and therefore consumed only in the places where the plant was native. Shortly before Táng, tea began to undergo a process of manipulation that prepared it for transport as a commercial good, which favoured the expansion of its consumption throughout the rest of China.

Tea leaves were steamed, ground and pressed together with some binding substance in the form of bricks or cakes. Less scrupulous merchants adulterated the product with willow or sophora leaves to increase their profit.

At the end of the eighth century, tea was already a highly prized good not only by the Chinese but also by their neighboring peoples, such as the Tibetans and some peoples of the steppes. From the regions of Yúnnán and Sìchuān there were trade routes that crossed very steep areas where caravans of merchants carrying tea transited. One of these routes was the so-called Tea Horse Road (茶馬道 Chá Mǎ Dào), which we have already talked about on other occasion.

Another region that was noted for tea production during Táng is Zhèjiāng 浙江. When Tea refers to the prefectures of Yuè 越 and Yúháng 餘杭, it is referring, respectively, to the present-day region of Zhèjiāng and the city of Hángzhōu 杭州, the most important municipality in this province. In Hángzhōu the Fùchūn 富春 river, formerly known as the Zhè River (浙江Zhè jiāng), which gives the province its name, flows into the sea. This river is an important commercial artery of the area, and from there boats loaded with tea departed for distribution to other regions.

Fùchūn 富春 river, in Zhèjiāng 浙江.

6

酒謂茶曰:阿你不聞道:

jiǔ wèi chá yuē: ā nǐ bù wén dào:

劑酒干和,博錦博羅。

jì jiǔ gān hé, bó jǐn bó luó.

蒲桃九醞,於身有潤。

pú táo jiǔ yùn, yú shēn yǒu rùn.

玉液瓊漿,仙人杯觴。

yù yè qióng jiāng, xiān rén bēi shāng.

菊花竹葉,君王交接。

jú huā zhú yè, jūn wáng jiāo jiē.

中山趙母,甘甜美苦。

zhōng shān zhào mǔ, gān tián měi kǔ.

一醉三年,流傳千古。

yī zuì sān nián, liú chuán qiān gǔ.

禮讓鄉閭,調和軍府。

lǐ ràng xiāng lǘ, diào hé jūn fǔ.

阿你頭惱,不須乾努。

ā nǐ tóu nǎo, bù xū gān nǔ.

Translation:

Wine said to Tea: "Ah, you have never heard of the medicinal liqueurs Gānhé, Bójǐn, Bóluó, Pútáo, Jiǔyùn. They have health benefits. Yùyè and Qióngjiāng are in the cup of immortals. Júhuā and Zhúyè are associated with the emperor. [...]

[Wine] gives priority to villages and towns, and reconciles the government and the military. Ah, your head is confused, no need to exert effort.”

Commentary:

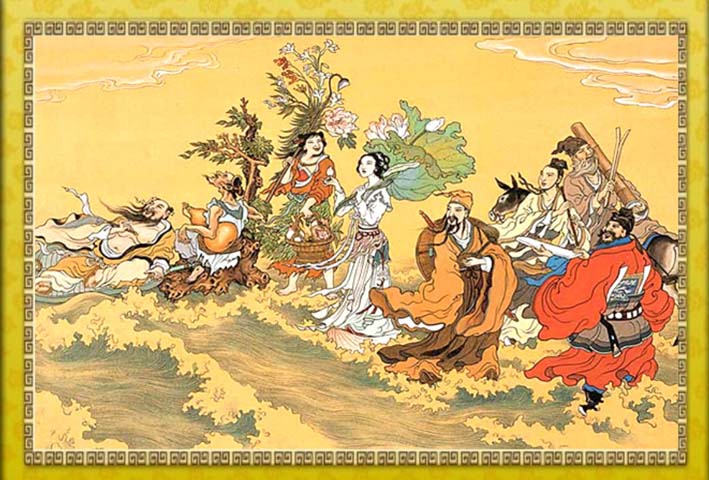

In this passage, Wine mentions a number of medicinal liqueurs that were consumed by immortals (仙 xiān) and emperors.

Jiǔyùn 九醞 appears to be the oldest known method of distillation of báijiǔ 白酒 ("white liqueur"), while qióngjiāng 瓊漿 was so prized that it was believed that whoever drank a cup of this liqueur became immortal.

These so-called "immortals" were sages and hermits who sought immortality or longevity through the practice of alchemy and meditation. Apart from society, they appreciated the enjoyment of the moment and drunkenness.

In the last part of this intervention, Wine once again emphasizes its role in ritual as a guarantor of social order.

The Eight Immortals (八仙 bāxiān) of Taoism.

7

茶謂酒曰:

chá wèi jiǔ yuē:

我之茗草,萬木之心,

wǒ zhī míng cǎo, wàn mù zhī xīn,

或白如玉,或黃似金。

huò bái rú yù, huò huáng sì jīn.

名僧大德,幽隱禪林。

míng sēng dà dé, yōu yǐn chán lín.

飲之語話,能去昏沉。

yǐn zhī yǔ huà, néng qù hūn chén.

供養彌勒,奉獻觀音。

gōng yǎng mí lè, fèng xiàn guān yīn.

千劫萬劫,諸佛相欽。

qiān jié wàn jié, zhū fó xiāng qīn.

酒能破家敗宅,廣作邪淫,

jiǔ néng pò jiā bài zhái, guǎng zuò xié yín,

打卻三盞之后,令人隻是罪深。

dǎ què sān zhǎn zhī hòu, líng rén zhī shì zuì shēn.

Translation:

Tea answered Wine: I am míng cǎo, the heart of plants. I am white like jade, or yellow like gold. Famed monks of great virtue [in] serene and hidden Buddhist temples, drinking [tea] are able to ward off confusion. I am Maitreya's provision and tribute to Guān Yīn. For a thousand or ten thousand kalpas, the various Buddhas delight [in me] and admire [me]. Alcohol can destroy the family and ruin the house, and promotes adulterous behavior. After three cups, it only causes profound crimes."

Commentary:

With this intervention, Tea is associated with the Buddhist religion and its high values. Tea is a plant that grows in highlands, in mountainous and isolated regions. Therefore, Buddhist monasteries, which were located in these remote places, were responsible for the production of tea.

In addition, Buddhism, which rejected alcohol and all intoxicating substances, found in tea an ideal drink, which also kept the mind awake by favouring awareness and meditation, qualities that Tea also highlights in this fragment of the text.

This association with Buddhism is further evident by the Buddhist terminology that Tea uses in its discourse. Jié 劫 is an abbreviation of jiébō 劫波, in Sanskrit kalpa, which in Buddhist cosmology refers to "eon", that is, a very long period of time. He also points out that tea is an appropriate offering for Buddhas and bodhisattvas, such as Maitreya (彌勒菩薩 Mílè Púsa, referred to in the text simply as Mílè 彌勒) and Guān Yīn 觀音.

Finally, Tea ends up attacking wine for the negative effects of drunkenness, which is consistent with the Buddhist precept of abstention from alcohol, which applied to both monks and lay people (although in the latter its non-compliance was not uncommon).

8

酒謂茶曰:

jiǔ wèi chá yuē:

三文一壺,何年得富?

sān wén yī hú, hé nián dé fù?

酒通貴人,公卿所慕。

jiǔ tōng guì rén, gōng qīng suǒ mù.

曾遣趙主彈琴,秦王擊缶。

zēng qiǎn zhào zhǔ dàn qín, qín wáng jī fǒu.

不可把茶請歌,不可為茶教舞。

bù kě bǎ chá qǐng gē, bù kě wéi chá jiào wǔ.

茶吃隻是腰疼,多吃令人患肚,

chá chī zhī shì yāo téng, duō chī líng rén huàn dù,

一日打卻十杯,腹脹又同衙鼓。

yī rì dǎ què shí bēi, fù zhàng yòu tóng yá gǔ.

若也服之三年,養蝦蟆得水病苦。

ruò yě fú zhī sān nián, yǎng xiā má dé shuǐ bìng kǔ.

Translation:

Wine replied: "Three coins for a bowl, since when do you have wealth? Wine is popular among nobles and admired by court officials. It made [the king of] Zhào play the qín, and the king of Qín play the fǒu. You can't sing with tea, and tea doesn't teach you to dance. Drinking tea produces pain in the waist, drinking a lot causes stomach problems. Drinking ten cups in a day causes bloating, [the belly] is like a drum. After drinking for three years, you'll look like a sick [swollen] frog."

Commentary:

Wine now alludes to the low cost of tea and, again, to the ritual function of wine, and also refers to a meeting between the kings of the states of Zhào 趙 and Qín 秦, from the Warring States period (戰國時代 Zhànguó Shídài), known as "meeting of Miǎnchí" (澠池之會 Miǎnchí zhī huì).

In this episode, the king of Qín wanted to provoke a war by insulting the king of Zhào. Being drunk, he asked him to play the sè 瑟 for him. The sè is a stringed instrument, which in this fragment of the Chá Jiǔ Lùn is named under the generic term qín 琴, which encompasses stringed instruments similar to the zither.

With this request, the king of Qín intended to humiliate his counterpart. But Lìn Xiāngrú 藺相如, one of the officers of the king of Zhào, saved his king's honour by putting the king of Qín in the same situation, getting him to play the fǒu, a percussion instrument made of clay.

"Meeting of Miǎnchí" (澠池之會 Miǎnchí zhī huì).

Then, Wine attacks the negative effects of tea. In the text, it is said "eating tea" (茶吃 chá chī), instead of "drinking tea", since tea in the Táng dynasty was consumed in a similar way to porridge with other ingredients. About this way of consuming tea in Táng we have already talked in our article From "Eating Tea" to "Drinking Tea": Tea Since Tang Dynasty.

Although today the beneficial properties of tea are well known, in Táng times the drink had its detractors. Among the negative effects associated with it was causing bloating and stomach problems.

9

茶謂酒曰:

chá wèi jiǔ yuē:

我三十成名,束帶巾櫛,

wǒ sān shí chéng míng, shù dài jīn zhì,

驀海騎江,來朝今室。

mò hǎi qí jiāng, lái zhāo jīn shì.

將到市廛,安排未畢,

jiāng dào shì chán, ān pái wèi bì,

人來買之,錢則盈溢。

rén lái mǎi zhī, qián zé yíng yì.

言下便得富饒,不在后日明朝。

yán xià biàn dé fù ráo, bù zài hòu rì míng zhāo.

阿你酒能昏亂,吃了多饒啾唧,

ā nǐ jiǔ néng hūn luàn, chī liǎo duō ráo jiū jī,

街中羅織平人,脊上少須十七。

jiē zhōng luó zhī píng rén, jǐ shàng shǎo xū shí qī.

Translation:

Tea said to Wine: "I acquired renown many years ago. Tea lovers cross seas and rivers, pay tribute and transport tea to the market. Before it has been arranged [in front of the customer], people come to buy it, and [merchants] overflow with wealth. Abundance comes to them now, no need to wait for tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. Ah, you Alcohol have the ability to confuse people. If they drink a lot, they boast. On the street, seven out of ten people [drinkers] go home on [someone else’s] back."

Commentary:

Tea once again emphasizes the mercantile value of the product and the fever it unleashed. In truth, the spread of tea consumption brought with it a revolution of culture. Tea was an alternative to alcohol as a socializing beverage and restructured social life in China.

In meetings between literati and members of the social elite, alcohol was always present as a social drink. Therefore, Buddhist monks, because of their precept against alcohol, remained out of these meetings. The prohibition of the use of alcohol to monks extended to all connection with this drink, from its consumption to its trade, through the prohibition of offering or giving alcohol as a gift, or any type of involvement in acts in which alcohol was present.

The spread of tea as a beverage and commercial asset during the Táng Dynasty would end this isolation of the monks. Tea came into competition with alcohol as a socializing beverage, facilitating relationships between monks and scholars, officials and poets.

Tea also became a vital component of the economy. Its consumption permeated all layers of society, and among the elite a refined culture developed that revolved around this drink. Experts and connoisseurs emerged who competed in meetings in which they tried to guess the origin or time of harvest of different varieties of tea. The rarest varieties reached exorbitant prices. Therefore, Tea is not bragging when it alludes in this way to the fever that unleashed its consumption and the wealth that the merchants amassed.

Lastly, the character gives a twist to the speech and ends his intervention by attacking the negative effects of drunkenness.

10

酒謂茶曰:

jiǔ wèi chá yuē:

豈不見古人才子,

qǐ bù jiàn gǔ rén cái zǐ,

吟詩盡道:

yín shī jìn dào:

渴來一盞,能生養命。

kě lái yī zhǎn, néng shēng yǎng mìng.

又道:酒是消愁藥。

yòu dào: jiǔ shì xiāo chóu yào.

又道:酒能養賢。

yòu dào: jiǔ néng yǎng xián.

古人糟粕,今乃流傳。

gǔ rén zāo pò, jīn nǎi liú chuán.

茶賤三文五碗,酒賤盅半七錢。

chá jiàn sān wén wǔ wǎn, jiǔ jiàn zhōng bàn qī qián.

致酒謝坐,禮讓周旋,

zhì jiǔ xiè zuò, lǐ ràng zhōu xuán,

國家音樂,本為酒泉。

guó jiā yīn lè, běn wéi jiǔ quán.

終朝吃你茶水,敢動些些管弦!

zhōng zhāo chī nǐ chá shuǐ, gǎn dòng xiē xiē guǎn xián!

Traducción:

Wine replied: "You don't see that the ancient men of talent said in their poems: 'drinking a cup can give life'. And also, 'alcohol is medicine that dispels sadness'. And also 'wine can nourish virtue'. The sayings of the ancients have been passed down to this day. Tea is cheap, three coins for five bowls; the cost of wine is seven coins per half cup. [People] send alcohol to thank or apologize and to express courtesy and socialize. The nation's music is due to wine. Drinking tea all day, dare to move some strings!”

Commentary:

Wine has long been associated with poetry, and Chinese poets have often expressed their feelings through it. Tea would also inspire countless poets from the Táng Dynasty onwards, but until then wine was the quintessential beverage.

In this part of the speech, Wine alludes to these facts, and then re-emphasizes the economic value of the drink. He ends by highlighting the value of liqueur as a means of socialization and as an inspiration for musicians. By "moving strings," Wine refers to playing a musical instrument.

11

茶謂酒曰:

chá wèi jiǔ yuē:

阿你不見道:男兒十四五,莫與酒家親。

ā nǐ bù jiàn dào: nán ér shí sì wǔ, mò yǔ jiǔ jiā qīn.

君不見猩猩,為酒喪其身?

jūn bù jiàn xīng xīng, wéi jiǔ sāng qí shēn?

阿你即道:茶吃發病,酒吃養賢。

ā nǐ jí dào: chá chī fā bìng, jiǔ chī yǎng xián.

即見道有酒廣酒病,不見道有茶瘋茶顛?

jí jiàn dào yǒu jiǔ guǎng jiǔ bìng, bù jiàn dào yǒu chá fēng chá diān?

阿闍世王為酒殺父害母,劉伶為酒一醉三年。

ā dū shì wáng wéi jiǔ shā fù hài mǔ, liú líng wéi jiǔ yī zuì sān nián.

吃了張眉豎眼,怒斗宣拳,

chī liǎo zhāng méi shù yǎn, nù dǒu xuān quán,

狀上隻言粗豪酒醉,不曾有茶醉相言,

zhuàng shàng zhī yán cū háo jiǔ zuì, bù zēng yǒu chá zuì xiāng yán,

不免求守杖子,本典索錢。

bù miǎn qiú shǒu zhàng zǐ, běn diǎn suǒ qián.

大枷磕頂,背上拋椽。

dà jiā kē dǐng, bèi shàng pāo chuán.

便即燒香斷酒,念佛求天,

biàn jí shāo xiāng duàn jiǔ, niàn fó qiú tiān,

終身不吃,望免迍邅。

zhōng shēn bù chī, wàng miǎn fù jiè.

Translation:

Tea replied, "Ah, you haven't heard: people don't enter wine houses until they are fourteen or fifteen. You don't see that the gibbon lost its life to alcohol. You have said that when you drink tea you become sick, and when you drink alcohol you nourish virtue. But don't you see the opposite? Ajatashatru killed his parents for alcohol; Liú Líng was drunk for three years [...] The canga on the head, the beams on the back. [The drunkard] burns incense and quits alcohol. He chants the name of Buddha begging to Heaven, and he does not drink for the rest of his life, hoping to avoid trouble."

Commentary:

Tea returns to the attack on the effects of drunkenness. In China, there was a belief that apes possessed supernatural and medicinal properties, and they were very fond of alcohol. The term xīng xīng 猩猩 refers to an indeterminate class of ape, translated here by "gibbons", since geographically it is the most plausible meaning, although perhaps it could also refer to orangutan.

There are many legends about ape spirits, a topic that we have already touched on in our article The Origins of Sun Wukong. According to the Compendium of Materia Medica (本草綱目 Běncǎo Gāngmù), apes were lured with wine and caught in order to kill them and take their blood to dye clothes. Probably, Tea is referring to this ploy when it states that "the gibbon lost its life to alcohol."

Ajatashatru (阿闍世王 Ādūshìwáng) was an Indian prince of Buddha's time. He is said to have killed his father, King Bimbisara, although there are different versions of the story. In some, the reason was because he wanted to inherit the throne, in others out of hatred of the Buddhist religion, in others the father killed himself. We don't understand what role alcohol plays, or why his mother is mentioned.

Tea also mentions the myth of Liú Líng 劉伶, one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Forest (竹林七賢 Zhúlín Qī Xián). Liú Líng was addicted to alcohol and had a great ability to drink. One day he passed by the establishment of the famous wine producer Dù Kāng 杜康.

Dù Kāng claimed that one cup of his wine was capable of sleeping a tiger, two cups could put a dragon to sleep, and that if someone drank three cups and was not drunk for three years he did not have to pay. Liú Líng drank the three cups, despite the recommendation against it from the vintner, and then found that he had no money to pay. The winemaker told him that he himself would go to Liú Líng’s house to get the money after three years.

Arriving at his home, Liú Líng fell asleep heavily and his wife thought he had died, so Liú Líng was buried. Three years later, the vintner went on to collect the debt and the wife, furious and blaming him for having caused the death of her husband, told him that she would pay it if he returned her husband. At this, Dù Kāng laughed and told her that her husband was only drunk. Indeed, after digging up Liú Líng and opening the coffin, they found him babbling praise about Dù Kāng's good wine.

Liú Líng 劉伶.

The final argument of Tea contains several eight-character lines, which gives an idea of despair in his speech.

Just as the expression "eat tea", the formula "he does not drink for the rest of his life" is used here, referring to alcohol. This is because in the past wine was made with fermented glutinous rice (called láo zāo 醪糟), and probably contained lumps. This usage has remained to this day in some dialects in China.

This is the final intervention of Tea, which closes the turn of the two main debaters, and a third character appears here who closes the debate.

12

兩家正爭人我,不知水在旁邊。

liǎng jiā zhèng zhēng rén wǒ, bù zhī shuǐ zài páng biān.

Translation:

The two sides are discussing. They don't know that Water is near.

Commentary:

The third character is introduced in these lines: Water. Let's see what he has to say.

13

水謂茶酒曰:

shuǐ wèi chá jiǔ yuē:

阿你兩個,何用匆匆?

ā nǐ liǎng gè, hé yòng cōng cōng?

阿誰許你,各擬論功!

ā shuí xǔ nǐ, gè nǐ lùn gōng!

言辭相毀,道西說東。

yán cí xiāng huǐ, dào xī shuō dōng.

人生四大,地水火風。

rén shēng sì dà, dì shuǐ huǒ fēng.

茶不得水,作何相貌?

chá bù dé shuǐ, zuò hé xiāng mào?

酒不得水,作甚形容?

jiǔ bù dé shuǐ, zuò shèn xíng róng?

米曲乾吃,損人腸胃,

mǐ qū gān chī, sǔn rén cháng wèi,

茶片乾吃,礪破喉嚨。

chá piàn gān chī, lì pò hóu lóng.

萬物須水,五谷之宗。

wàn wù xū shuǐ, wǔ gǔ zhī zōng.

上應乾象,下順吉凶。

shàng yīng qián xiàng, xià shùn jí xiōng.

江河淮濟,有我即通。

jiāng hé huái jì, yǒu wǒ jí tōng.

亦能漂蕩天地,亦能涸殺魚龍。

yì néng piāo dàng tiān dì, yì néng hé shā yú lóng.

堯時九年災跡,隻緣我在其中。

yáo shí jiǔ nián zāi jì, zhī yuán wǒ zài qí zhōng.

感得天下欽奉,萬姓依從。

gǎn dé tiān xià qīn fèng, wàn xìng yī cóng.

由自不能說聖,兩個何用爭功?

yóu zì bù néng shuō shèng, liǎng gè hé yòng zhēng gōng?

從今以后,切須和同,

cóng jīn yǐ hòu, qiē xū hé tóng,

酒店發富,茶坊不窮。

jiǔ diàn fā fù, chá fāng bù qióng.

長為兄弟,須得始終。

cháng wéi xiōng dì, xū dé shǐ zhōng.

若人讀之一本,

ruò rén dú zhī yī běn,

永世不害酒顛茶瘋。

yǒng shì bù hài jiǔ diān chá fēng.

Translation:

Water said to Tea and Wine: "Hey, you two, how in such a hurry! Who praises you? Everyone evaluates your merits. With words and gossip you destroy each other. The four elements of life are earth, water, fire and air. What is tea without water? What is wine without water? If rice is eaten dry, it damages the intestines and stomach. If the tea is ingested dry, it will hurt the throat. All things in the universe need water, the ancestor of the five cereals. The upper is according to Heaven, the lower obeys destiny. The Yangtze and the Huái flow because of me. I can fill heaven and earth and make fish and dragons die of thirst. Among the ruins of the nine years of the disaster of the time of Yáo, I was the only cause. Thanks to this, the world admires [me] and [people of] all surnames obey. Although I cannot call myself a sage, what need is there to argue on your merits? From now on you must cooperate with each other, so that the wine houses are prosperous and the tea houses are not poor. As brothers from beginning to end. So if someone reads this play, he will not be harmed by [excess of] alcohol or tea."

Commentary:

Water intervenes here to bring order and rebukes both debaters for their mutual attacks. Note that it cites the four elements (四大 sì dà) that belong to the Buddhist tradition, rather than the five elements or Five Phases (五行 wǔxíng) of the indigenous Chinese tradition. On the other hand, Heaven is cited here as Qián 乾, which corresponds to one of the Eight Trigrams (八卦 bāguà) of the Yì Jīng 易經.

Water highlights the need for it both Tea and Alcohol, which was normally produced by fermenting rice, and in general all things in the universe. It also alludes to the floods that occurred during the reign of the mythical king Yáo 堯, which are related in the myth of Gǔn Yǔ (鯀禹治水 Gǔn Yǔ Zhì Shuǐ), which we have already talked about in our article The Three Sage Kings. These floods lasted nine years and were eventually controlled by King Yǔ 禹.

The Gǔn Yǔ myth (鯀禹治水 Gǔn Yǔ Zhì Shuǐ).

Water ends its speech, and thus concludes the text, urging Tea and Wine to cooperate and advocating a moderate consumption of both substances, so that they are not harmful to health and that trade can prosper. Its last sentence, which is addressed to the public, shows that the Chá Jiǔ Lùn is a text to be represented, oriented to entertainment.

The symbolic function of the Cha Jiu Lun:

In Pearse's analysis, the two main characters of the text, Tea and Wine, are understood as metaphors, on the one hand, of Buddhism and the native Chinese religions (Taoism and Confucianism) respectively and, on the other, of the foreign and the native.

The third character, Water, which appears at the end of the text, would also be representative of the integration of the Three Religions or Teachings (三敎 sān jiào), and his discourse reconciles the positions of the previous two.

To reach this conclusion, Pearse relies on the terminology used by the respective characters. As we have already seen, Tea’s interventions are riddled with references to the Buddhist religion, originally from India.

On the contrary, the discourse of Wine represents the ritual practice and traditional Chinese morality, typical of Confucianism and Taoism, both native currents of China. We have already seen, too, how Wine alludes to the Confucian virtues, and to their essential role in the fulfillment of ritual, which in Confucianism is essential for the proper functioning of the social order.

But Wine, although not so clearly, also alludes to Taoism. References to this religion can be seen in the mention of the immortals and the varieties of medicinal wines they drank.

Finally, Water makes use of vocabulary characteristic of the three religions. As we have already mentioned, it mentions the four elements of the Buddhist tradition, while the mentions of the floods of Yáo's reign and the Yì Jīng speak of a Confucian influence. Finally, Pearse sees in Water's emphasis on the harmony between Tea (Buddhism) and Wine (Confucianism) a Taoist idea, and in the very substance of water a metaphor for Dào 道.

In this way, Water would be presented as the synthesis or amalgam of the Three Religions, and as a conciliator of Chinese culture with the foreign.

Final considerations:

As we have seen, the Chá Jiǔ Lùn is a satirical text that represents the interreligious debates of the Chinese imperial court, making a mockery of both cultural and religious ethnocentrism that existed until that time.

Had it been a purely Buddhist text, as it has been interpreted on several occasions, it would have been logical that the winner of the debate would have been Tea, the banner of Buddhist values. And yet this is not the case.

In the religious debates that took place in the court, the three religions were officially discussed. However, since Confucianism was the state religion, its role was not questioned, and in reality the debates were mainly between Buddhism and Taoism. The winner of these debates was determined by the emperor, who acted as judge.

In Táng times, these debates began to advocate for harmonious coexistence between the three religions, and continued to be represented as simple entertainment. This reconciliation was especially driven by Buddhism, as a foreign religion, in an attempt to assimilate into Chinese society.

It is noteworthy, finally, that in Dūnhuáng the Buddhist prohibition of alcohol was often ignored by both lay people and monks. The reason for this violation of Buddhist precepts lay in the difficulty of obtaining fresh water to drink. Alcohol was therefore part of everyday life in Dūnhuáng, and in fact the monasteries, in addition to buying alcohol, produced their own.

Sources:

Tea in China: a Religious and Cultural History, James A. Benn. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2015

Negotiating Religious and Cultural Diversity in Tang China: An Analysis of the Cha jiu lun 茶酒論, Amy Pearse. The Student Researcher, 4 (1), 2017