Introduction

In the past, Manchu men shaved their heads except for a circle of hair on the crown, which they let grow long and picked up in a braid or queue. This traditional way of wearing hair is known in Chinese as biànzi 辮子, and was imposed by manchu rulers on the local population after the conquest of China and the establishment of the Qīng 清 dynasty in 1636.

The biànzi eventually became a public symbol of submission to the regime. In the nineteenth century, due to the growing contact of the West with China, the biànzi was known in Europe and America as "Chinese queue", although it was not a traditionally Chinese style. It has subsequently been popularized in Hong Kong films set in the era, especially in Kung Fu films.

Origin of the biànzi

Although widespread throughout China due to the imposition of the Qīng government, the biànzi was a much older tradition among the nomadic peoples of the northern steppes. Already during the Hàn 漢 dynasty, Xiōngnú 匈奴 nomads wore biànzi. Other Tartar tribes also wore similar hairstyles, including some of those who established dynasties in China, such as the Khitan (Liáo 遼 dynasty, 907–1125) and the Jurchen (Jīn 金 dynasty, 1115–1234).

Among the Chinese, it was normal to wear long hair on the entire head, symbol of virility, collected in the back in ponytails or buns, and it was also common to wear caps or turbans on the head, such as the fútóu 襆頭.

Emperor Tàizōng of Jīn 金太宗 already ordered in 1179 that all his Chinese subjects wear Tartar clothing and hair style.

At the end of the Yuán 元 dynasty (1271-1368), of Mongolian origin, the biànzi was already common in China, although most natives still wore long hair all over the head tied on the crown.

With the restoration of an indigenous government in the Míng 明 dynasty, foreign styles were banned, allowing only inhabitants of Tartar origin to wear biànzi in accordance with their ancestral customs.

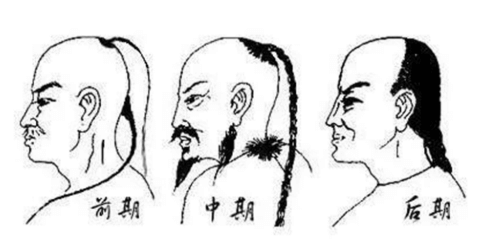

Three styles of biànzi.

The imposition of the biànzi

Finally, with the Manchu conquest of the sixteenth century, it was imposed on Chinese men to shave their heads (xuēfà 削髮), leaving only a queue on the crown. This order was progressively implemented in different regions, in the decades of 1620-1630.

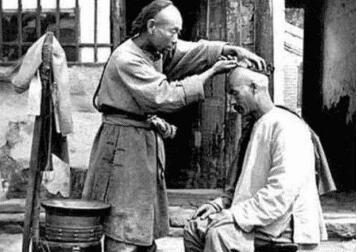

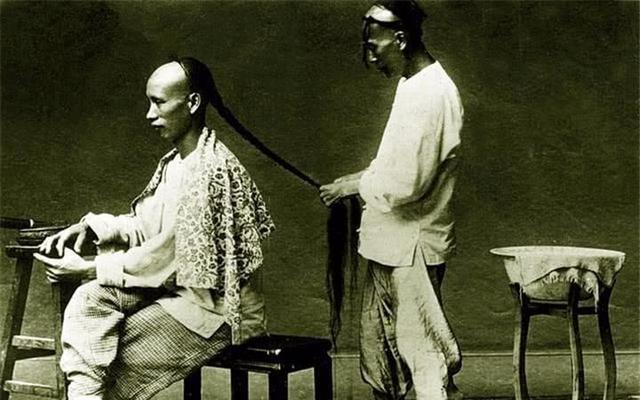

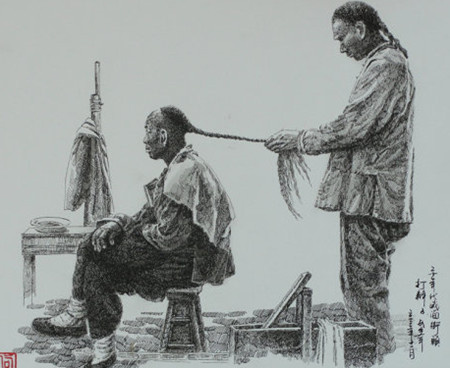

Barber shaving the head of a customer, leaving the biànzi on the crown.

Although in more recent times this order has been presented as a violent imposition, which would have forced the Chinese to choose between keeping their hair or keeping their heads, it seems that this view is the result of later nationalist rhetoric, and that the Qīng government tried to apply this rule in softer ways than simply resorting to violence.

One of these ways was the appeal to Confucian filial piety, which assimilated the ruler-governed relationship with the father-son family relationship, in which the son must aspire to resemble the father as much as possible. On the other hand, the new dynasty rewarded with official positions those talented men belonging to the elites who agreed to comply with the change.

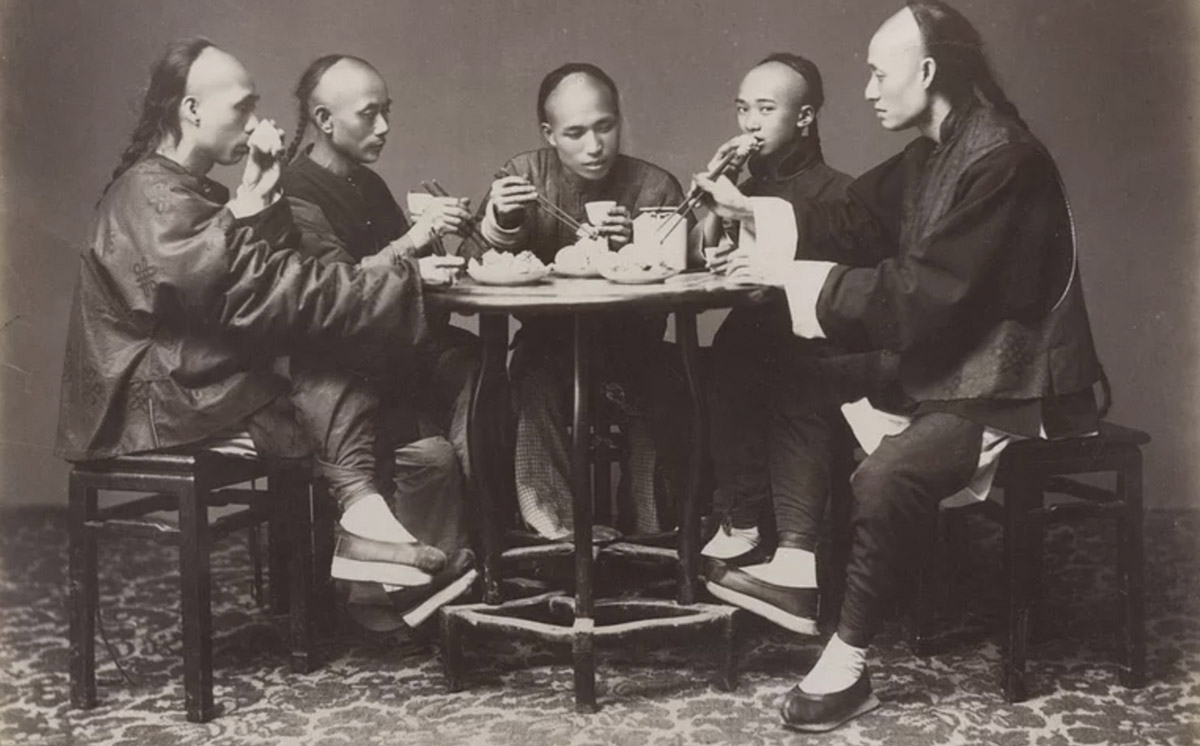

A group of men with biànzi.

However, some Chinese found it more difficult to accept the biànzi than to accept the Manchu government. In 1653, the death penalty began to be applied to those who refused to comply with the order.

Although some officers resisted and preferred to die, the majority of the population complied with the order. Especially in the south, where the population had had less contact with the Tartar tribes and this practice was stranger, the order to wear the biànzi met with greater resistance. In some places it resulted in armed rebellions, which were finally suppressed.

Be that as it may, the biànzi became a symbol of submission to the dynasty and those who did not wear it were identified as bandits and rebels.

This order to wear the biànzi did not apply to women, in whose aspect the Manchus did not interfere. Nor did they interfere in the custom of binding their feet, although they themselves did not practice it with their women.

Because all males had to wear the biànzi, shaving their heads every three or four days,

that of barbers was one of the most widespread professions.

Resistance to the biànzi

It seems that the resistance that arose to the imposition of the biànzi among the Chinese population would not have been due so much to the fact of wearing the queue but to the fact of shaving part of the head. As we have already mentioned, hair was associated with virility; the eunuchs had their heads shaved after castration. Cutting hair was also a punishment applied to criminals.

The nationalist literature of the twentieth century has praised those who resisted complying with the order, and has exaggerated the involvement of the queue, associating it with humiliation, and presenting long hair as a sign of patriotism. However, this literature overlooks the fact that many high-ranking officers who requested to keep their hair in the traditional style accepted and recognized Manchu sovereignty.

This fact shows that nationalism and anti-Manchu sentiment were not such present phenomena at that time. Resistance to cutting one's hair was not necessarily an act of rebellion, at least until the nineteenth century, when nationalist sentiment grew, which fueled several rebellions. The rebel groups of this time used the hair as a symbol of resistance.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, under increasing foreign influence, hair became a symbol of backwardness with respect to modernity. Young people sent to study in the U.S. were mocked and many cut off their braids. The Chinese delegation had to intervene to ensure that the rule was respected.

In Guǎngzhōu 廣州 and in Guǎngdōng 廣東 province, which during the nineteenth century was a hotbed of insurrections and rebel groups, these went around the streets in search of locals wearing the queue, and many Chinese hid it under their caps to avoid being targeted or being pointed as traitors to the homeland for supporting the Manchu regime.

The Tàipíng 太平 rebellion carried out systematic killings of Manchus, the largest of them after assaulting the city of Nánjīng 南京, in which they killed the entire Manchu population of about forty thousand inhabitants.

In the early twentieth century western uniforms were given to the army, and many soldiers hid the biànzi under their caps; some students of military academies even cut off their queues.

Soon after, the Manchu prince Zàitāo 載濤, returning from a trip abroad in which his queue had been mocked, and citing the Japanese example of haircut as a first step to modernization, petitioned the government for the abolition of the queue in the army.

An intense debate began on this. Some argued that the ponytail was a danger to those working with modern machinery, as it could get caught producing accidents. Others, that loyalty to the government did not depend on the style of hair one wore.

When the state was still debating the issue, many officers already adopted modern haircuts. However, the government did not interfere and no reprisals were taken.

Finally, on December 7, 1911, the obligation of the biànzi was officially abolished, shortly before the abdication of the last Manchu prince, which ended the dynasty and the Chinese imperial era.

Conclusion

After the abolition of the mandatory biànzi, many people continued to wear it for years. The new Republic of China launched a campaign against it, seeing it as a sign of backwardness, a vestige of a feudal regime. Many replaced this braid with western-style haircuts, and therefore of equally foreign origin.

However, many public figures kept it, despite having been integrated into modern society.

We believe that the association of the biànzi with the support of the Manchu regime, and the association of the long hair as a nationalist symbol, are phenomena that emerged in the nineteenth century during the last years of the dynasty. As we have seen in other articles (Secret Societies and The Origin of Triads), nationalism and anti-Manchu sentiment, while certainly existing among certain minority groups, were not widespread among the bulk of the population during the early days of Manchu rule.

For more detailed information on the biànzi, see the article The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History, on which we have relied mainly to write this article.

Sources:

- Culture, Institution, and Development in China: The economics of national character, C. Simon Fan. Routledge, 2016.

- Michael Godley 'The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History'. December 1994, East Asian History nº 8.

2 thoughts on “The Imposition of the Biànzi, the Manchu Queue”

I think there may be a typo, and 1953 may be the wrong year:

“However, some Chinese found it more difficult to accept the biànzi than to accept the Manchu government. In 1953, the death penalty began to be applied to those who refused to comply with the order.”

Hi Jacqueline,

Thanks for your message. Definitely, it’s a typo, and a big one!

The year is 1653. We corrected it already.

Thank you for pointing it out!