Lóulán 樓蘭 was an ancient kingdom that flourished in the 2nd century BC on the margins of the Silk Road. It was an independent city-state until the Hàn dynasty 漢朝 took control of the region, and proliferated for some more centuries until it was mysteriously abandoned in the 3rd century of our era, leaving only ruins that remained buried in the desert sands for nearly two millennia.

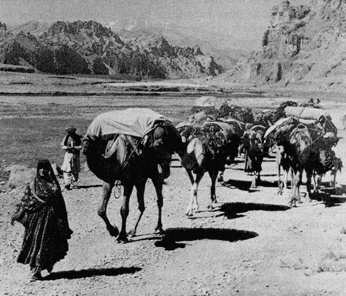

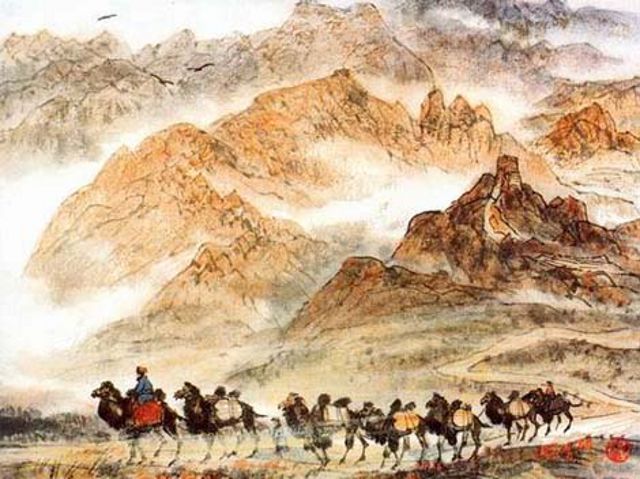

The Taklamakan Desert (塔克拉玛干沙漠 Tǎkèlāmǎgān Shāmò), known as "the place of no return", was the first major obstacle that caravans that travelled along the ancient Silk Road (丝绸之路 Sīchóu Zhīlù) were to avoid. Arriving there, the main route divided into two, one branch that ran south, and another to the north, along the Tarim River (塔里木河 Tǎlǐmù Hé) basin. This river flowed into a large saltwater lake, the Lop Nur (羅布泊 Luóbù Pō), on whose banks the kingdom of Lóulán prospered from trade.

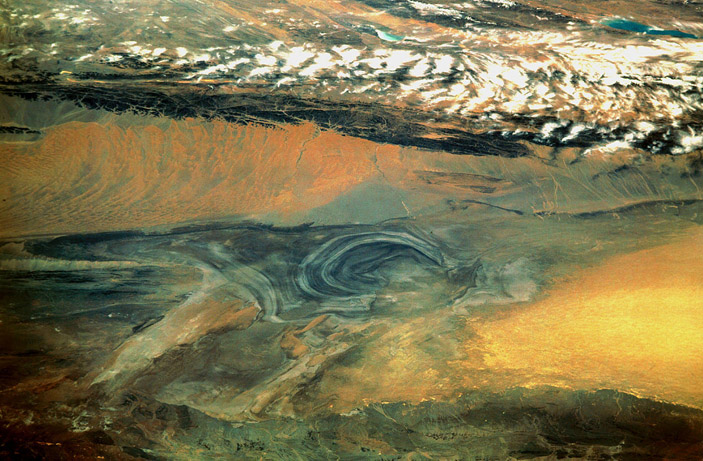

Lop Nur

Lake Lop Nur was a large saltwater lake that today, due to the agricultural use of water from the rivers that fed it, is dry, appearing only in the form of small seasonal lakes. In the 1920s, its area covered more than 3,000 square kilometers.

Lop Nur (羅布泊 Luóbù Pō) dry basin, satellite view.

In the 1990s, China used this place for nuclear testing.

Lóulán was one more of the long chain of fortified oasis on the Silk Road, a must-stop for caravans of traders running between China and Central Asia. Like the other independent kingdoms of the region, it was often the target of dispute between China and the Xiōngnú 匈奴 kingdom, due to its strategic position for trade.

The contest for control of Lóulán

The famous traveler Zhāng Qiān 張騫 crossed the region in the 2nd century BC as an envoy of the Hàn dynasty with the mission of entering into an alliance with the Western Regions (西域 Xīyù). When, after Zhāng Qiān's mission, new missions were sent to the West, these were attacked by troops from the kingdoms of Lóulán and Gūshī 姑師, the Hàn empire commanded an army in retaliation to subdue Lóulán, which agreed to pay tribute to the Hàn court.

At the same time, Lóulán suffered the attacks of the Xiōngnú empire, which was also interested in controlling the region. In the face of this situation, the king of Lóulán also decided to pay tribute to the Xiongnú. Lóulán thus maintained a system of alliances with the two kingdoms, sending princes as hostages to both courts, in a difficult balance that did not please the Hàn. Upon the death of a king, the hostage princes were sent back to Lóulán, and the new king in turn sent his sons.

When, on the death of one of the kings, a prince who had been held hostage in the Xiōngnú kingdom was enthroned, the Hàn demanded that the new sovereign appear in court. But the Hàn empire had previously failed to return one of the princes, and the king decided to refuse.

Thus, Lóulán's troops began attacking the envoys of the Hàn dynasty again, until in 77 BC a delegation was sent by the emperor of China with the mission of killing the king. Bringing gifts to the monarch, the envoys were received in Lóulán, getting the king killed when he was drunk and hanging his head from one of the city's towers.

Although the king's younger brother succeeded him on the throne, the kingdom came under the control of the Hàn empire, which renamed it Shànshàn 鄯善.

The kingdom of Lóulán was known in the local language as Krorän. When the Hàn dynasty took over the region in 77 BC, it was renamed as Shànshàn 鄯善. The imposition of a Chinese name was a way of symbolizing new sovereignty. However, the region remained known as Lóulán by the local population.

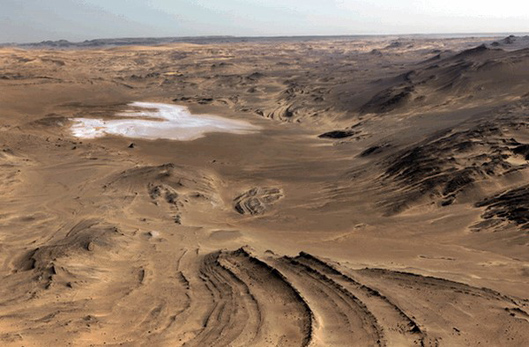

Ruins of an ancient city in Lóulán.

From that moment on, the kingdom of Lóulan was under the control of the Hàn dynasty intermittently, alternated with periods of independence and others of coalition with the Xiōngnú. Eventually, the Hàn Empire established a permanent military colony in Lóulán.

In the 3rd century, the city of Lóulán was abandoned. The military garrison was displaced to another city to the south, and the kingdom of Shànshàn survived for a few more centuries, until the Táng dynasty 唐朝, but was eventually also abandoned by its inhabitants. When monk Xuánzàng 玄奘 crossed the region in 645, there was no trace of human life in the cities of the kingdom.

The cause of this abandonment has been a mystery to historians for decades.

Swedish archaeologist Sven Hedin.

Discovery of Lóulán ruins:

On 28 March 1900 an expedition led by the Swedish archaeologist Sven Hedin passed near Lop Nur Lake. At one point, Hedin realized that he had lost his only iron shovel, and commanded his local guide to find it. A sandstorm caught the guide by surprise, and when the storm passed, he found himself in the midst of the ruins of an ancient city: Lóulán.

The remains of Lóulán

The archaeological excavations have shown that there was a vibrant culture throughout the kingdom. Known to Western archaeologists as "the Pompeii of the Desert," in Lóulán different kind of buildinhs have been unearthed, such as palaces, Buddhist temples and pagodas, residential houses, and underground tunnels that brought water from nearby rivers to supply the populations. Coins, documents, silk fabrics, lacquers, wood carvings and bronze artifacts have also been rescued. Some of these objects show Greco-Roman influences, which demonstrate the importance of this enclave in trade routes.

In the surroundings there are remains of dry rivers and crops, suggesting that a certain agriculture was practiced in the region.

The karez

The peoples that inhabit the Tarim basin have been using for centuries underground water channels that in the local language, Uighur, are called karez. These canals take advantage of the difference in altitude and gravity to collect water from the melt in the mountains and bring it down to the oases. These channels are similar to those unearthed in Lóulán and are still used today.

This system of underground channels prevents the flowing water from being blocked by sandstorms, and minimizes evaporation losses, as temperature on the ground surface can reach extreme temperatures, close to 80 degrees Celsius.

Today, around the town of Turpan (吐鲁番 Tǔlǔfán), which feeds on these karez, around a thousand of these canals run along about 5000 kilometers supplying water throughout the region. These tunnels are about one meter high, so their construction has to be done lying down, and the earth is brought to the surface by the same wells that serve to extract the water.

But the most interesting discoveries in Lóulán are surely the so-called "Tarim mummies", wrapped in cotton and silk, dating up to 1,800 years before Christ, demonstrating the existence of human populations in the region in this early period. These mummies show Caucasian features, suggesting that the inhabitants of the Lóulán kingdom came from the Iranian plateau.

One of these mummies, known as the "Lóulán Beauty" is 3,800 years old and is in perfect condition.

The "Lóulán Beauty".

Causes of decline

The abandonment of Lóulán has long been a mystery to history. Among the factors that caused the displacement of its inhabitants, war, plagues, movements of the course of the Tarim and Lop Nur, and the opening of other trade routes, all have been considered.

However, recent studies show that the abandonment of Lóulan may have been due to an ecological disaster caused by the expansion of the Chinese empire to the west. The diversion of rivers for agricultural purposes could cause scarcity in lowlands and the gradual deterioration of the oases.

According to Hàn dynasty records, Lake Lop Nur covered an area of between 17,000 and 50,000 square kilometers. The remains show that the climatic conditions of the region were considerably wetter two thousand years ago. However, the expansion of the Hàn empire was only possible through the establishment of troops and fortified cities and the displacement of new settlers. These troops demanded arable land in an area where agriculture had not previously been intensively practiced, which would have required the diversion of a large amount of water.

Farming areas in the Tarim basin were, during the Hàn dynasty, considerably larger than even in the 1950s, thus causing the dissecation of rivers and the depletion of the oases. Historical documents record this decrease in flow in rivers, as well as the reduction in troop grain rations in the second half of the 3rd century.

Between that time and the 7th century, the Lóulán civilization would gradually sink, until the region was completely abandoned and finally swallowed by the desert sands.

In Chinese, Lóulán has become figuratively meaning "dreaming", "daydreaming," so that from someone who dreams while awake, he is said to have gone to Lóulán (去楼兰 qù Lóulán).

In Chinese, Lóulán has become figuratively meaning "dreaming", "daydreaming," so that from someone who dreams while awake, he is said to have gone to Lóulán (去楼兰 qù Lóulán).

Sources:

- Mischke, S., Liu, C., Zhang, J. et al. The world’s earliest Aral-Sea type disaster: the decline of the Loulan Kingdom in the Tarim Basin. Sci Rep 7, 43102 (2017).