Introduction:

In the previous articles on the afterlife we have exposed the fundamental concepts about the realm of the dead and the journey to the underworld, analyzed the ideas that led to the development of the myth of the Ten Courts of King Yánluó (十殿閻羅 shí diàn Yánluó), and analyzed the concept of "death in vain" (枉死 wǎng sǐ) or premature death, with the terrible consequences that it entails.

We recommend reading them to better understand this article; however, we are going to briefly summarize here the process that soul follows after death.

After death, the soul is transferred to the world of the dead (yīnjiān 陰間) through the Ghost Gate or Gate of Spirits (鬼門關 guǐ mén guān). From there, the deities guarding the door move the soul to the first of the ten courts of the underworld. The soul will spend three years until it is put on trial by each of these courts, and punished according to its actions in life.

Remember that this underworld is not a hell in the Christian sense of the word, but rather a purgatory through which all souls must pass on their way to their next existence.

The end of the journey: the River of Oblivion

After the tenth trial in the last of the courts of the underworld, the soul is free, ready to be reincarnated. But to do this it must first cross the so-called River of Oblivion (忘川 Wàng Chuān).

At the end of the Yellow Springs Road (黄泉路 Huángquán lù) is the Nàihé 奈何 River. The river flows from hell and its flow is of blood and smells of rot.

This river already appears in the descriptions of the underworld of the Táng 唐 dynasty. However, in the manuscript found in Dūnhuáng 敦煌 that tells the story Mùlián Rescues His Mother (目連救母 Mùlián jiù mǔ) it is mentioned as Nài hé 奈河, or Nài River (note the change in the second character). Above this river is a bridge (奈河橋 Nài hé qiáo) that souls must cross to reach their reincarnation.

In the Míng 明 dynasty, this river began to be known as Nàihé 奈何, short for wú kě nài hé 無可奈何, which we can translate as "having no alternative".

Bridge over the Nàihé 奈何.

Next to the river is the so-called Stone of Three Lives (三生石 Sānshēng shí), where souls can find inscribed everything about their previous, present and future life. On the bridge, an old woman named Mèng Pó 孟婆 forces the deceased to ingest a potion, known as "Mèng Pó soup" (孟婆湯 Mèng Pó tāng), which will make the soul forget its previous existence. That is why the Nàihé River is also known as Wàng Chuān, that is, River of Oblivion.

Mèng Pó seems to originate in the Qīng 清 dynasty and the first mention of her appears in the Jade Records (玉歷寶鈔 Yùlì Bǎochāo). It seems that both Mèng Pó and the concept of the River of Oblivion could be derived from the influence of Greek mythology and the River Lethe (厲司河 Lìsī hé).

Mèng Pó 孟婆 and the soup of oblivion.

The Silver and Golden Bridges

The few souls who had led an exemplary and virtuous life on earth did not have to cross the Nàihé bridge. For them were reserved the Golden Bridge (金橋 jīn qiáo) and the Silver Bridge (銀橋 yín qiáo).

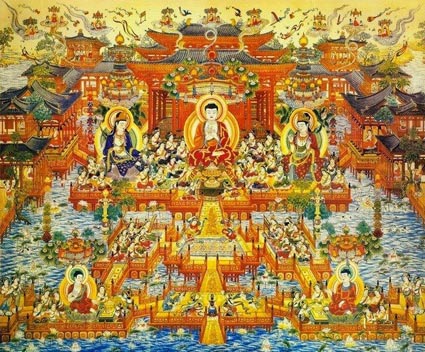

The first led to the Pure Land of the West (Xīfāng Jí Lètǔ 西方極樂土 or Jìngtǔ 淨土) of Amitabha Buddha (Āmítuófó 阿彌陀佛). When the spirit of the deceased beheld Amitabha's face, it gained immediate liberation, entering nirvana.

Pure Land of the West (Xīfāng Jí Lètǔ 西方極樂土).

The silver bridge led to Heaven (Tiān 天), where the Jade Emperor (Yù Dì 玉帝) ruled, and the soul that crossed this bridge would become part of the cast of immortals and deities that resided there.

According to some narratives, the three bridges were parallel to each other. Others offer a vision of the bridge over the Nàihé on three levels: a higher level through which virtuous souls pass and which can be traveled without difficulty; a middle level through which souls who have committed both sins and virtuous actions are to cross, which must be walked with great care because it entails difficulty; and finally a lower level through which evil souls must cross. This lower level is slippery, and is riddled with ghosts and copper snakes and iron dogs (銅蛇鐵狗 tóngshé tiěgǒu) pushing the souls trying to cross.

To those who fall into the river, appalling suffering awaits them, and they will never be able to reincarnate again. Faced with this cruel fate, the living burn offerings of paper boats so that these souls have the opportunity to cross the river by boat and reincarnate.

The Six Realms of Existence or Six Paths of Reincarnation

After crossing the River of Oblivion, the soul will be reborn in one of the six realms of existence (liùqū 六趋 or liùdào 六道), according to its karma. This conception originates from Indian Buddhism.

These realms are those of gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hells; and they are ordered on a scale according to the amount of pain and pleasure found in each of them.

Representation of the six realms of existence (liùdào 六道).

In the realm of the gods or devas, (天人 tiānrén), they enjoy all the pleasures of existence, without any worry or lack. It is a life of pleasures that inevitably leads to the development of attachment to them.

Demigods or asuras (阿修羅 āxiūluó) are angry deities who enjoy greater pleasures than humans but at the same time envy the life of the gods, and therefore are not able to enjoy such pleasures.

The third realm, that of human beings, is the luckiest of all, precisely because it has equal parts pleasures and sufferings. Suffering, if not excessive, is the spark that ignites the flame of spiritual search, and the first of the four Noble Truths1. Human beings have the possibility of realizing the reality of suffering and the existence of a way out of it: the Buddhist dharma and the possibility of attaining nirvana.

Immediately below the human realm is the animal kingdom, which in Buddhism is associated with impulses, instinct, and mutual destruction.

Almost completely below, in fifth place, are the hungry ghosts (餓鬼 èguǐ). These are beings who suffer from continuous hunger and thirst, the result of a karma of attachments in previous lives. They are always looking for something to put in their mouths, but nothing satisfies them. It is said that only the aroma of incense gives them a moment of satiety.

Hungry ghost (餓鬼 èguǐ).

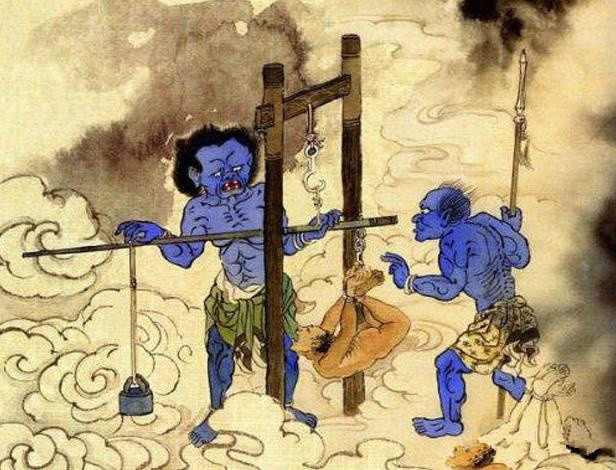

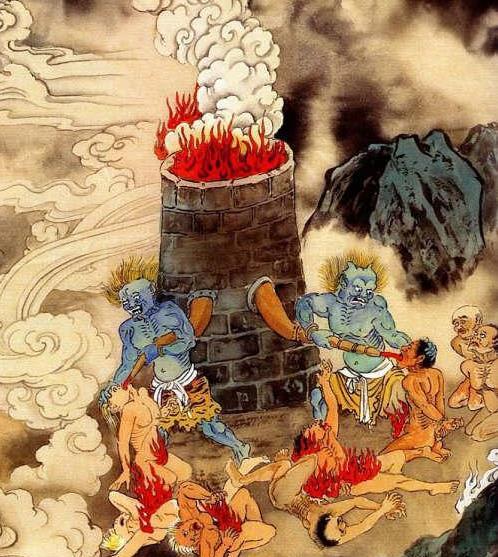

Finally, at the lowest level of existence, there are hells. There are hells of fire and frozen hells, which include different forms of suffering. In China, they are also known as dìyù 地獄, or as "eighteen dìyù" (十八地獄 shíbā dìyù), representing different levels. Although the Six Realms of existence are of Indian origin, this concept of the eighteen hells is a Chinese creation. In each of them different tortures are applied, the worst imaginable.

Images of the hells (十八地獄 shíbā dìyù).

Existence in any of the six realms is always temporary; when the bad karma of past lives is consumed, one is reborn again in another realm and have a new opportunity.

The Ghost Festival

On the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month of the Chinese calendar, the Ghost Festival (鬼節 guǐ jié) is celebrated. In Taoism and Buddhism this festival is known as Zhōng Yuán 中元節 and Yúlánpénhuì 盂蘭盆會 Festival, respectively.

According to Chinese beliefs, on this day, the Ghost Gate is opened so that souls who are in the underworld can cross into the realm of the living and visit their relatives.

During this day, the living burn incense, prepare food offerings, and burn paper money for the deceased. Some believe that with this money, souls can bribe the deities of the underworld to make their transit more bearable.

Although this holiday seems to have a Buddhist origin, the way of understanding it is genuinely Chinese: the concern for the ancestors and their stay in the afterlife. This date is also the end of summer and the beginning of the harvest season, in which sacrifices are made to the land.

Final conclusions:

Throughout this series of articles we have seen how the world of the living (yángjiān 陽間) and the realm of the dead (yīnjiān 陰間) are in interrelation and mutual interaction, and how the soul of the deceased has to cross the dark regions and face terrible punishments after being judged by the ten courts of the underworld.

"Death in vain" is a cause of continuing concern in the Chinese mindset; the spirits of people who die from this type of death can become neglected and become ghosts, causing problems in the human world.

After the trials in the underworld, the soul crosses the River of Oblivion, detaching itself from the memories of its past life, and enters one of the six realms of existence, being reborn again.

Chinese mythology about the afterlife has gradually formed, including aspects of the system of government of the world of the living, to create an "underworld bureaucracy" that administers justice in a manner similar to that of the earth.

Although many of these ideas about the afterlife have been borrowed from Indian Buddhism, we see in them an imprint of the ancient beliefs and mentality of the Chinese. This mythology has been formed as a dialogue, a consensus between the different religious currents of China, both indigenous and foreign, which have been integrated into the amalgam that we know as "popular religion".

This folk religion is a rich and complex mosaic, sometimes encompassing contradictory narratives. Chinese religions lack divine revelation like those of Western monotheisms. Different texts have been appearing progressively, adding or modifying previous ideas, and all of them enjoy some degree of authority in religious matters.

Finally, in the figure of Mèng Pó and her soup of oblivion, already in recent times, we see the influence of Greek mythology and the Western world.

Chinese beliefs about the ancestors and the world of the dead condition the practices and customs of the living, which are a way of expressing affection for their ancestors, as if they were still among them.

Notes:

1. About the Four Noble Truths, see Life of the Buddha.

Sources:

Religion and Religious Practices in Rural China, Mu Peng. Routledge, New York, 2020.

In Search of the Supernatural: The Written Record, Bao Gan, Kenneth J. DeWoskin, James Irving Crump. Stanford University Press, Standford, California, 1996.

Dizang and the Three Kings: Constructing Buddhist Hell by Imitating the Bureaucratic System in the Tang Dynasty, Xiao Jiang. Department of History, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China.

The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism, Stephen F. Teiser. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1994.

The Journey to the West, Revised Edition, Volume 1, Anthony C. Yu. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

4 thoughts on “The Afterlife in Chinese Culture (IV): The River of Oblivion and Reincarnation”

Is there any connection(s) with this topic and the forms in tai chi telling a similar story?, thank you, Ed

Hi Ed,

Thanks for your comment. The forms in Taichi?? I am afraid I do not know anything about that. However, I doubt it, since Taichi is more related to Taoism than to Buddhism. But maybe there is and I do not know… Please let us know if you find out.

Regards

The “river of oblivion” does not necessarilly point to any greek influence, it can have an independent origin. And where did the greek get it from then?

This articule does not nention Taoism, which evolved from the original beliefs of the shamanic culture of ancient China, it influenced much of these beliefs.

Hi Marcos,

Thanks for your contribution.