Introduction

Poetry has always been one of the most appreciated arts in China. In the past, the taste for poetry extended to all layers of Chinese society, and at certain times poetic composition was one of the requirements in official examinations for the public civil servant, so that any literate was able to compose poems.

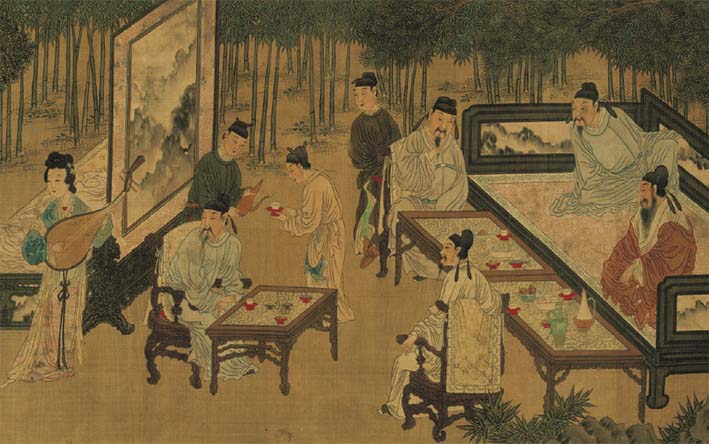

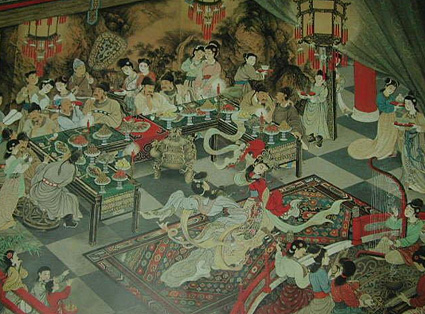

No surprisingly, then, poetry contests arose, in which the participants competed, either by reciting poems or by composing them on the spot. These duels or contests of poetry are called dǒu shī 鬥詩, were practiced as a pastime at festivals and banquets and took different forms, almost always involving the consumption of wine among the participants.

Wine has always been an important element among Chinese society in meetings and celebrations. Since ancient times, at least since the Qín 秦 dynasty (221-206 a.C.), the Chinese had fun participating in various games in which the loser had to drink a stipulated amount of wine. Among the most famous of these games is the so-called tóuhú 投壺, which consists of throwing arrows with the hand into a vessel placed at a certain distance. The one who got more arrows inside was the winner, and the loser had to drink.

Illustration of three women playing tóuhú 投壺.

Over time, these games evolved to include poetic skill and knowledge as game elements. We will cite below some of the most common.

“Wine measure in the Golden Valley”

jīngǔ jiǔshù 金谷酒數

The name of this competition comes from a preface to a book of poetry, known as Jīngǔ shī xù 金谷詩序 ("Preface to the Poems of the Golden Valley"). This text describes the celebration of a banquet that took place during the reign of Emperor Yuánkāng 元康 of the Hàn 漢 dynasty, in a place known as "Golden Valley" (金谷 Jīngǔ). As part of the fun, attendees competed by improvising poems expressing their feelings. When one of the participants failed to compose a poem successfully, he had to drink three measures of wine as a penalty.

From that time on, the expression jīngǔ jiǔshù began to be used to refer to this type of poetic contest, where jiǔshù 酒數 (measure or quantity of wine) is a stipulated amount of wine, usually three cups. The famous poet Lǐ Bái 李白 refers to this type of game in some of his writings.

A well-known episode of somewhat unusual and dangerous poetic contest took place in the final years of the Hàn dynastyn when Cáo Zhí 曹植, forced by his brother Cáo Pī 曹丕, had to compose a poem in the time he took to walk seven steps, as a condition to save his life (to know more, see A Poem in Exchange for the Life of Cáo Zhí).

“Floating cup in winding brook”

liú shāng qū shuǐ 流觴曲水

While jīngǔ jiǔshù was practiced in northern China, another kind of poetic contest emerged in the south, called liú shāng qū shuǐ 流觴曲水 ("floating cup in winding brook"). This game took place on the shores of a brook or stream of water on whose banks the participants lined up and in which someone, upstream, dropped a few floating cups of wine.

When one of these cups stopped on the shore in front of one of the participants, he had to compose a poem on the spot and, if he could not produce a poem that satisfied the rest of the attendees, had to drink the liquor from the glass.

This was the game that originated the Lántíngjí Xù 蘭亭集序, when Wáng Xīzhī 王羲之 wrote his calligraphy masterpiece.

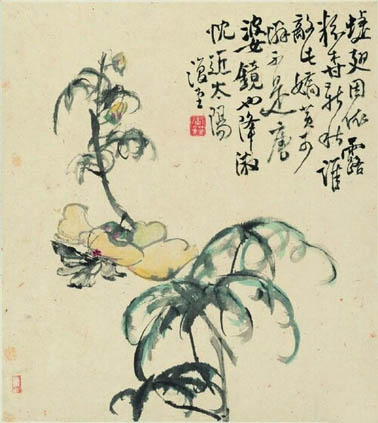

“Flying flowers contest”

fēi huā líng 飛花令

Fēi huā líng 飛花令 (“flying flowers contest”), which appeared during the Táng 唐 dynasty, is perhaps the most popular of this kind of games.

This contest is not based on composition but on recitation, and requires a high degree of knowledge of the poetry of large numbers of authors.

There are several ways to play, but the most common is as follows. First, a word is chosen and the order of participation is set. The first participant must then recite a verse from a well-known author in which the chosen word comes first. The second participant will then recite another verse in which the word comes in second place, and so on until the round is completed.

As an example, let's imagine that the chosen word is "flower" (花 huā). The first participant could begin with the verse by Mèng Hàorán 孟浩然:

花落知多少

huā luò zhī duō shǎo

How many flowers fall?

(Note that the word flower, 花 huā, is in first place).

The second participant can then continue with this verse by Lǐ Bái 李白:

五花馬,千金裘

wǔ huā mǎ, qiān jīn qiú

A flecked horse, a fur worth a thousand pieces of gold

(Here the word huā 花 does not possess the literal meaning; yet it is second in the quoted verse.)

In turn, a verse valid for the third participant would be the next one, by Zhāng Ruòxū 張若虛:

月照花林皆似霰

yuè zhào huā lín jiē sì xiàn

The moon shines in the flowery forest, resembling hailstones

And so on. If one of the participants is wrong and recites a verse in which the chosen word is not in its correct place on that turn, or is unable to remember an appropriate verse, he must drink as a penalty.

The name of this game comes from the poem Hánshí 寒食 ("Cold Food") by Hán Hóng 韩翃, whose first verse reads:

春城無處不飛花令

chūn chéng wú chǔ bù fēi huā líng

It's spring, and there's not a single place in town where flowers are not falling

Other poetry contests

During the Sòng 宋 dynasty chàngchóu 唱酬 ("exchange of poems") appears, a practice in which one of the participants composes a poem, and the other responds with another, following the same metric and rhyme. This practice reached great popularity during the Qīng 清 dynasty.

Similar to the chàngchóu is the xíngjiǔlíng 行酒令 ("walking wine"), consisting of composing verses in turn so that they are in accordance in structure and meaning. As the name suggests, the wine is again involved in the game, as a penalty to those who fail.

All these practices show the importance and dissemination that poetry has had for much of China's history. Even today, Chinese television organizes and broadcasts programs with such contests involving competitors of all ages.