Introduction:

The jiàn 劍 is a straight double-edged sword that appeared as a military weapon in the times of the Zhōu 周 dynasty. However, over time its use would be abandoned on the battlefield in favour of the sabre (刀 dāo), and it became a symbolic and ritual weapon, maintaining its use in exhibitions and in self-defense, and would end up being associating with scholarship and the upper class.

The jiàn as a military weapon:

The jiàn appeared in the Western Zhōu 西周 dynasty (1046-781 BC) as a secondary weapon in the military field. Being a short weapon, it was not the main combat choice, and was generally used as a last resort; a defensive weapon rather than an offensive one. This sword is a versatile weapon, which allows both cutting and slashing techniques and thrusting techniques, and is also easy to carry on the waist.

Zhōu 周 dynasty sword.

The jiàn appeared simultaneously to the jǐ戟 halberd, which has a pointed end to thrust; until then the dagger-axe or gē 戈 halberd was mainly used.

The dagger-axe is a long pole weapon, with a sharp blade perpendicular to the pole at the distal end of it. To use the gē effectively, it was necessary to oscillate the weapon, so it is inferred that the combats were not in closed formation, since in this case it would have been extremely difficult to use, and would have posed great risk to the rest of the troop.

The jǐ, on the other hand, added on the structure of the dagger-axe a tip to thrust. The appearance of the jiàn and the jǐ therefore reflect a change in the way of fighting, from combat in open formation with oscillating weapons to combat in compact formation with weapons whose main function is to thrust and lunge.

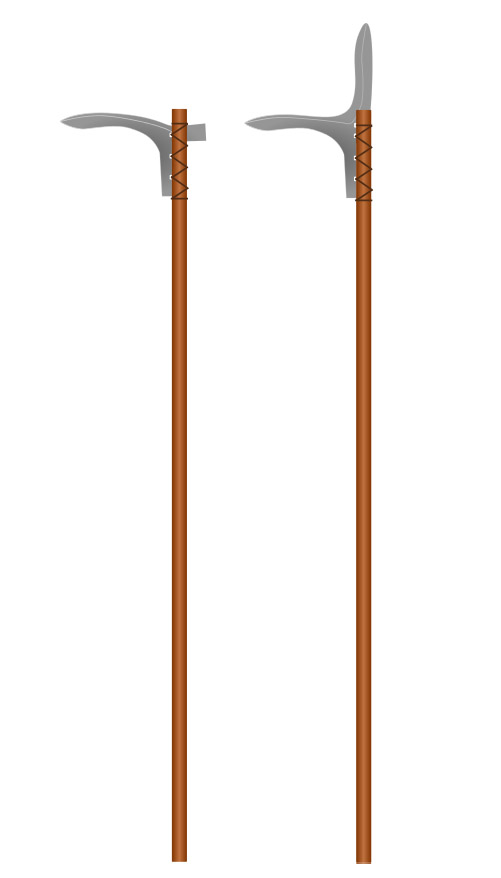

Gē 戈 (left) and jǐ 戟 (right) halberds.

Swords of the Zhōu period had a blade of between 28 and 46 centimeters. In the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代 Chūn-Qiū Shídài), due to the developments in metallurgy, they reach up to 56 centimeters of blade, mainly in southern China, since there the combat was based on infantry, while in the north chariot warfare was prevalent at the time.

During Hàn 漢, jiàn remained popular. Some swordsmen (劍客 jiànkè) made a living from their fencing skills. These were especially abundant in the areas bordering with the steppes, where the garrisons stationed there faced frequent incursions by steppe peoples. Fencing shows were often organized, a discipline that despite its dangerousness became a pastime of poets and aristocrats.

Bronze sword of the Hàn 漢 dynasty (202 BC-220 AD).

However, little by little the use of the straight sword in the military field was abandoned in favour of the sabre. This change began already during Hàn and by the end of the Three Kingdoms Period (三國時代 Sānguó Shídài) was already consolidated.

Sabres were heavier and sturdier, and they didn't break as easily. Having a single edge, the structure of the sabre allowed the back of the blade to be thicker and provided the weapon with greater robustness.

Another factor that favoured this change was, possibly, the amount of training needed to master the weapon. The sabre could be handled effectively with less training than the sword, so when it came to training troops it was a more efficient choice.

The jiàn was more elegant and remained the favourite weapon of a few warriors, as well as in aesthetic displays and sword dances.

The jiàn outside the military sphere:

In a non-military context, the straight sword remained as a symbolic and ritual weapon in the equipment of emperors and high officials, and also in Taoist rituals.

Since the Jìn 晉 dynasty, swords carried in the court were made of wood. This shows the fact that self-defense in court was no longer essential. And despite this, the sword, even made of wood, remained an important symbol of martial orientation; court officials were armed, even if only ritually.

It should be said here that ritual weapons acquired their symbolic value by dissociating themselves from the possibility of combat. Ritual weapons often had special characteristics: they were too heavy to be handled effectively, or they were made of special materials, such as jade. Despite retaining its form, its meaning went beyond the martial realm.

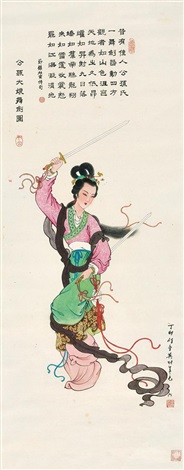

The use of the jiàn was also maintained in sword dances (劍舞 jiàn wǔ). Until the Táng 唐 dynasty (618-907), these dances were derived from combat techniques and were performed by warriors within martial circles as a form of training. However, in Táng appeared a purely aesthetic form of sword dance, performed by women without any relation to the world of martial arts, as a form of entertainment for the court.

The most reputable of these artists was Guān Gōngsūn 觀公孫, whose fame was immortalized in a poem by Dù Fǔ 杜甫. In this poem, entitled Watching a Disciple of Guān Gōngsūn Perform Sword Dance (觀公孫大娘弟子舞劍器行 Guān Gōngsūn dàniáng dìzǐ wǔ jiàn qì xíng), this poet of the Táng dynasty tells us that, because of her skill in this type of dance, Guān Gōngsūn was the first among the eight thousand assistants of Emperor Táng Xuánzōng 唐玄宗.

The poet, who in his childhood once saw Gōngsūn dancing, was so impressed that he would keep that memory for the rest of his life. Almost fifty years later, watching a young woman dance in a special way, he wanted to know from whom she had learned, and it turned out that her mentor had been Gōngsūn herself.

Sword dances would later be incorporated into Chinese opera (戲曲 xìqǔ).

Illustration of Guān Gōngsūn 觀公孫, the most famous dancer of the Táng Dynasty, performing a sword dance.

Later, in the Sòng 宋 dynasty (960-1279), martial arts exhibitions were part of entertainment shows at government events. Until then, civil rulers and men of letters could practice martial arts and maintain their status as Confucian gentlemen. But in Sòng the martial arts and the military suffered a significant loss of prestige and began to be despised by the Chinese civilian elite. Even the practice of archery, which had been regarded by Confucius and his followers as a high demonstration of correct conduct, was rejected by them.

Civilian officers ruled by virtue, education, and intellect, not by their skill as men of arms, and were considered morally superior to military officers. This change in Chinese mentality would last for centuries, and would not be reversed until after the fall of the Míng 明 dynasty (1368-1644) and the establishment of the Manchu dynasty, at which time a balance between the civil (文 wén) and the martial (武 wǔ) began to be sought.

During the Yuán 元 dynasty (1271-1368), the Mongols still made use of the jiàn on the battlefield. The reasons for this are not entirely clear, but it is believed that it is due to the nature of the war between nomadic peoples.

The Chinese had an army equipped by the state, with its regulatory and standardized weapons, and received equal training for all from the state. The Mongols, on the other hand, whose socio-political structures were not so defined, lacked such regular troops. When they rose for war, men came with their own weapons and their own martial training. It is possible, therefore, that they used straight swords snatched by pillage in raids on Chinese territory, by the mere fact of their availability.

However, this brief resurgence of the jiàn declined rapidly in the Míng Dynasty. The contempt of the military arts by the civilian elite, which had begun in Sòng, continued during this time. Perhaps because the jiàn was not a military weapon, it gained new meaning for civilian officers. Educated men could practice jiàn fencing without associating themselves with militarism, and thus the straight sword was associated with scholars and literati.

The jiàn became, therefore, a refined weapon appreciated only by gentlemen, and began to be collected also as an object of art. An esoteric aura was created around this weapon. Jiàn swordsmanship became a mark of deep erudition, and it was precisely the non-military character of the weapon that allowed this to happen.

Martial arts scholars of the Míng Dynasty determined that there were five or six fencing schools existing at that time, which were present among the civilian population but not in the army.

In this way the jiàn was associated with subtlety, with the spirit, and was completely dissociated from physical strength. The practice with the sword made it possible to find a balance in the lives of civil officers in the service of the state and represents, in some way, the reconciliation between the principles of wén and wǔ.

The famous poet Lǐ Bái 李白 of the Táng Dynasty

was also known to be one of the best swordsmen of his time.

Conclusions:

The jiàn appeared almost three millennia ago as a military weapon, but quickly lost this status in favour of the sabre, which was a more robust weapon and required less training.

The straight sword was nevertheless maintained as a ritual and symbolic weapon, in Taoist ceremonies and in sword dances, whose value was purely aesthetic.

Fencing of the jiàn represented the reconciliation of civil and martial principles during the Míng dynasty, and the character that this weapon acquired in popular culture is maintained even today. The most famous schools of sword in today's martial arts belong to the so-called "internal styles" (內家 nèijiā), whose philosophy agrees perfectly with the image of the jiàn as a subtle weapon, in which physical strength is not relevant.