Introduction:

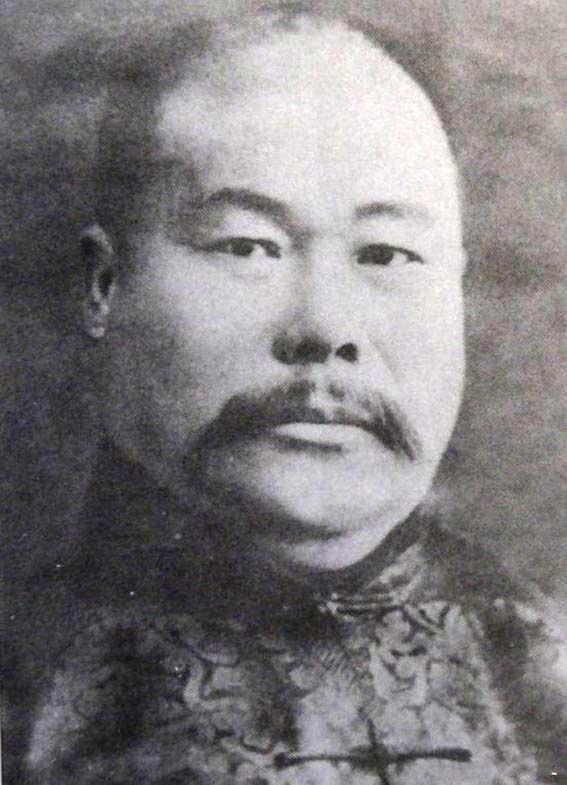

The "ten essential points" of Tàijíquán (太極拳十要 Tàijíquán shí yào) are a series of key principles for the practice of this martial art. They were dictated orally by Master Yáng Chéngfǔ 楊澄甫 and recorded by his disciple Chén Wēimíng 陳微明.

Each of these points constitutes an essential principle of practice, and in the text recorded by Chén Wēimíng they are composed of a brief formula of a few characters followed by an explanation or commentary. The ten points are clearly exposed to be easily remembered, and we do not know if their formulation is due to Yáng Chéngfǔ or if they were transmitted orally to him by his family.

Master Yáng Chéngfǔ 楊澄甫.

We will present each of these points below. We do not want to reproduce here Chén Wēimíng's complete text, of which there are numerous translations, but we will present our interpretation on each point.

The Ten Essential Points of Tàijíquán

太極拳十要 Tàijíquán shí yào

- Light and sensitive energy at the top of the head

虛靈頂勁 xū líng dǐng jìn

The Chinese formula, xū líng dǐng jìn 虛靈頂勁, has no clear and apparent meaning. Another translation might be "insubstantial numinous energy at the crown of the head."

This phrase is actually a quote from the Tàijíquán Lùn 太極拳論, a fundamental text usually attributed to Wáng Zōngyuè 王宗岳, which reads:

虚領頂劤。氣沈丹田。

xū lǐng dǐng jìn. qì shěn dāntián.

Insubstantial numinous energy [ascends to] the crown. Qì sinks to the dāntián.

However, here líng 靈 is replaced by lǐng 領 (neck), which is homophone. Some authors believe that the lǐng 領 of the Tàijíquán Lùn is actually an error, since the terms xū líng 虛靈 often appear paired in neo-Confucian texts.

In any case, this first point refers to keeping the head upright, aligned with the spine, in a natural and effortless way, as if suspended from a thread by the crown, avoiding muscle stiffness, since otherwise qì and blood will not be able to circulate through the neck. In this way, Yáng Chéngfǔ tells us, the shén 神 (spirit) rises to the crown of the head.

Although Yáng Chéngfǔ does not speak here of sinking the qì to the dāntián, this is a consequence of containing the chest (see point 2).

- Contain the chest, round the back

含胸拔背 hán xiōng bá bèi

"Containing the chest" refers to keeping it relaxed, slightly sunken. The back, on the other hand, comes out. Rounding or pulling out the back is a consequence of relaxing the chest, and should not be done by muscle tension.

This position favours abdominal breathing, and causes the energy to sink to the dāntian and flow up the spine. The practitioner of Tàijíquán seeks to acquire the qualities of "heavy down, light up and flexible in the middle". When the breath is abdominal and the qì sinks, the centre of gravity of the body is lowered, achieving a good rooting and consequently the quality of being heavy in the lower part.

Yáng Chéngfǔ also tells us that pulling out the back favours that the qì adheres to the spine, so that the ability to "issue" (發勁 fājìn) can be executed perfectly. Also, rounding the back causes a correct alignment of the spine when redirecting the incoming energy of the opponent to the ground.

When the chest expands, the abdomen is blocked and breathing rises to the rib cage, raising the centre of gravity and becoming heavy up and light below, that is, losing rooting.

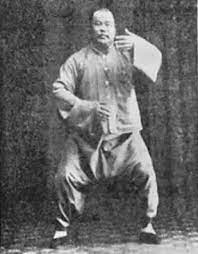

Yáng Chéngfǔ 楊澄甫, demonstrating the movement "cloud hands" (雲手 yún shǒu).

- Relax the waist

鬆腰 sōng yāo

Yāo 腰 refers not only to the anterior and lateral area of the waist, but also, and especially, to the posterior area, that is, to the lumbar and kidney area. The waist directs the body and controls the change of weight of the legs from full to empty (see point 4). By relaxing the waist, you can be "flexible in the middle".

Biomechanically, the rotation of the waist and hip generates acceleration and consequently increases the energy generated in the movement. In addition, the waist connects the lower and upper (see point 7).

- Separate empty and full

分虛實 fēn xū shí

The empty and the full refer to the distribution of the weight of the body on the feet. In Tàijíquán, it is said that the leg with weight is "full", and the leg without weight, "empty". The empty must be distinguished from the full so that the movements are agile and light, and maintain a stable position.

This also refers to the yīn 陰 - yáng 陽 dichotomy, where yīn is empty or light, and yáng is full or heavy. So "full" and "empty" are in interrelation as yīn-yáng: when one grows, the other decreases, and vice versa. When the weight is centred, yīn and yáng are in balance.

Yáng Chéngfǔ tells us that this skill is the essence of the practice of Tàijíquán. In Tàijí, we never move one foot without first having transferred our weight to the other. The distinction between full and empty makes the movements agile and fluid and the position stable. Otherwise, one will stumble. Despite being paramount, we don't know why Chéngfǔ places this skill in fourth place on his ten-point list.

But "distinguishing between full and empty" not only refers to one's own body, but also to the opponent's body. It is necessary to understand this in order to adapt to their actions.

Finally, "empty" and "full" can be extrapolated to all yīn-yáng pairs, i.e. soft-hard, retreat-advance, internal-external, lower-upper, etc.

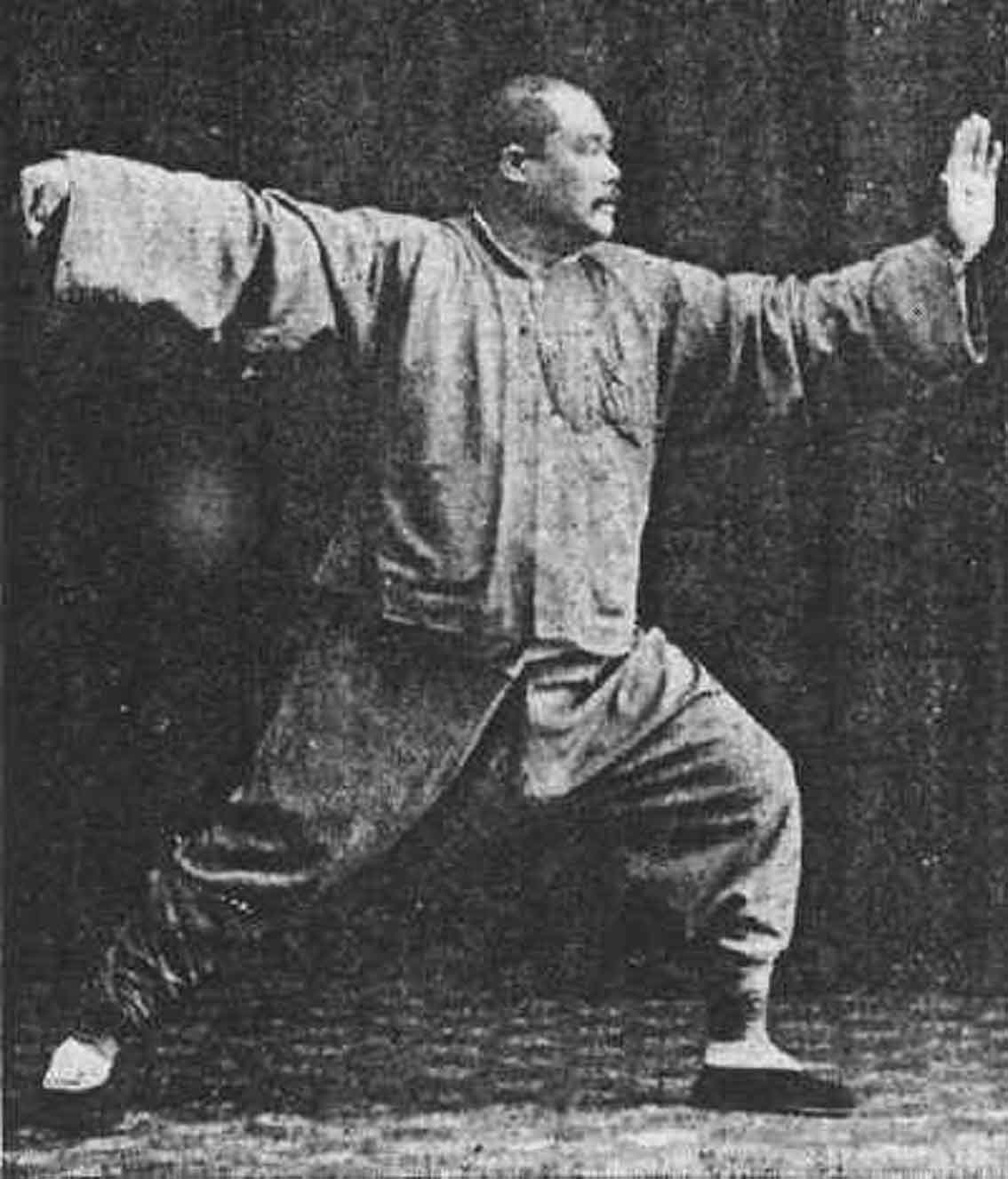

Chéngfǔ, demonstrating "single whip" (單鞭 dān biān).

- Sink the shoulders and drop the elbows

沈肩墜肘 shěn jiān zhuì zhǒu

This point is simple to understand; it means keeping your shoulders relaxed and your elbows down, letting them hang. If elbows are raised, shoulders are stiff and energy does not flow; the chest opens and qì rises and stagnates.

However, dropping the elbows does not mean closing them, sticking them to the trunk. A relaxed and open position must be maintained. The arms do not fully extend. This is a requirement to execute fājìn properly, since "issuing" is executed by the coordinated movement of the whole body, and not by the extension of the arms.

- Use intention and not physical force

用意不用力 yòng yì bù yòng lì

This is one of the most difficult points to understand. Yì 意 is often translated as "intention", but also refers to attention and alert. Lì 力 is understood in Tàijíquán as muscle power, as mere physical strength.

In the commentary, Yáng Chéngfǔ insists that tension should not be generated in the body. The use of physical force generates tension and muscle stiffness, which in turn blocks the flow of energy and blood through the body.

The concept of not using muscle strength is clearer, but what does it mean to "use intention"? Chéngfǔ insists on keeping the body relaxed and loose (鬆開 sōng kāi). Instead of using physical force, intention must be used. And where intention goes, energy follows (意之所至,氣即至焉 yì zhī suǒ zhì, qì jí zhì yān). From our understanding, putting the emphasis on "intention" seeks to avoid an excess of relaxation, that is, to avoid laxity.

If we imagine the level of muscle activation of the organism as a continuum, we can divide it into four stages, from lowest to highest activation. First of all we find laxity (懈 xiè); secondly, relaxation (鬆 sōng); next, tautness (緊 jǐn) and finally stiffness (僵 jiāng).

We understand laxity as a state in which the body is flaccid, floppy, lacking structure. It is an excessive relaxation, where there is no connection between the different parts of the body.

At the opposite level of the continuum is stiffness, understood as excessive muscle activation. The body is excessively tense, it is slow, energy does not flow and we are not able to react properly.

Both laxity and stiffness are extremes to avoid. Among them, at an intermediate point, are relaxation and tautness. Relaxation is a state in which the body is in balance, loose and flexible, but maintains a structure; it is solid and stable. Energy flows freely through it. This is the state we want to achieve in practice. Tautness, on the other hand, is the next level of muscle activation, to which we will go at certain times and only for the necessary time, such as when hitting or "issuing" (fājìn), and always in a controlled manner.

These levels of body activation are actually a reflection of the mind. If the mind is lax and devoid of intention, the body has no structure; if the mind is tense, the body tenses. And if the mind is relaxed, the body relaxes.

When Yáng Chéngfǔ speaks of "using intention and not force," he is impelling us to avoid rigidity and laxity both physically and mentally. In laxity there is no intention, there is no structure. "Intention", therefore, refers to maintaining the present mental focus towards the opponent, while the body is relaxed and flows freely in an agile and lively way.

- Upper and lower follow each other

上下相隨 shàng xià xiāng suí

Chéngfǔ, quoting the classical texts of Tàijíquán, says in his commentary: "Starting at the feet, crossing the legs, directed by the waist and expressed in the fingers. The process is continuous between one part and another."

In Tàijíquán, what happens in the hands is just an expression of what happens in the lower part of the body. The movement starts from the rooting of the feet on the ground, and is governed by the waist and expressed in the upper limbs.

The whole body has to move together. When one part moves, all move, when one does not move, all the others are also at rest. When we practice the form, the movement of the hands is in tune with the movement of the feet and with weight shifts; all parts move and arrive at the same time.

Chén Wēimíng 陳微明, demonstrating the handling of the jiàn 劍 or Chinese straight sword.

- Inner and outer mutually harmonize

內外相合 nèi wài xiāng hé

The external refers to the body; the internal refers to the mind. Like the body, intention also contracts and expands; inside and outside must work together.

The inner also encompasses the breath. In Tàijíquán, the breath "follows" the movement, that is, it adapts to it. This is the opposite of health or Qìgōng 氣功 exercises in which movement "follows" the breath. However, in Tàijí the breath is not controlled consciously, but flows naturally, adapting to the movement by itself.

- Continuity without gaps

相連不斷 xiāng lián bù duàn

According to Chéngfǔ, external martial arts (外家拳 wàijiāquán) make use of muscle strength (力 lì). In this way, energy is released and dissipated alternately, there being moments of pause between the end of one movement and the beginning of the next. These pauses would be a vulnerability, which a practitioner of Tàijíquán could take advantage of effortlessly.

In Tàijí, however, there is no interruption between movements, since these are not born of muscle strength, and intention is maintained at all times. This is the meaning of "continuity without gaps". The rupture does not refer only to movement, but also to attention, to the sense of alertness.

- Seek stillness in the movement

動中求靜 dòng zhōng qiú jìng

When practicing alone, Tàijíquán uses movements as slow and calm as possible, maintaining a calm and deep breath, so that the heart does not accelerate.

Here, "stillness" also refers to the mind and emotional balance. Yáng Chéngfǔ, in his commentary, again alludes to external martial arts, saying that its practitioners lose their breath and lack emotional stability.

Conclusions:

The ten essential points contain precise instructions for practice, although some of them are not obvious at first glance. The first five points deal with physical aspects or skills, while the next five refer to other, more subtle skills.

Every practitioner of Tàijíquán should become familiar with these ten principles, as they constitute the essence of this martial art. It is convenient to memorize them, although their understanding has to be progressively refined through practice, and understanding and developing the most subtle aspects usually takes years.

Tàijíquán, like any other style of Chinese martial arts, requires constant dedication and study applied throughout a lifetime.

Related articles: