Introduction

Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 is a martial arts system founded in 1836 by Chan Heung 陳享, one of the greatest martial artists of his time. Today it is one of the most widely practiced styles of Kung Fu in the world both for its effectiveness and for its great technical variety.

As with most Kungfu styles that emerged in the 18th-19th centuries, its origins are shrouded in legend. The data we have has been transmitted for the most part through oral tradition, and is unreliable.

In this series of articles dedicated to the history of the style, we will try to reconstruct its origins. However, due to the aforementioned scarcity of data, we will often throw more questions than answers. On the other hand, although many stories are undoubtedly legendary, they are part of a long tradition and therefore deserve to be told, because, although they say little about the real events they intend to tell, they say a lot about the ideals held by the masters and practitioners of the style of the time in which they emerged.

In this first article we are going to talk about the life of Chan Heung, the founder of Choy Li Fut.

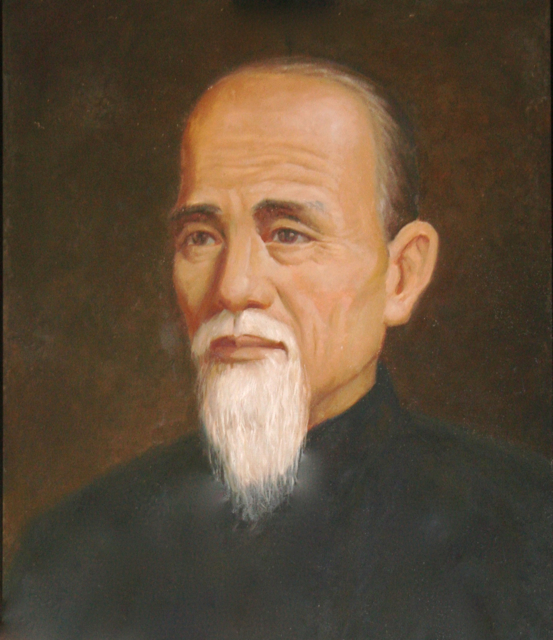

Portrait of Chan Heung 陳享.

Background: Southern styles and Shàolín mythology

Many styles of Kungfu that emerged in southern China in the time of Chan Heung make use of a common mythology. This mythology relates them to the legendary temple of Southern Shàolín 少林 (Nán Shàolín 南少林), from which they are supposedly descended.

Among these styles, the so-called "Five Family Styles" of Southern China stand out: Hung 洪家, Lau 劉家, Choy 蔡家, Li 李家 (pronounced "Lei"), Mok 莫家. These styles spread in Canton province (Guǎngdōng 廣東) in the second half of the eighteenth century, and were concentrated in the Pearl River (Zhū Jiāng 珠江) Delta region, the most populous and wealthy region of the province.

This area is also known to have suffered a large number of disputes between local clans over land and resources. Clans were broad family lineages; in Canton province these associations were particularly strong, and were organized around a common temple where the tablets of the clan's ancestors were worshipped.

It is interesting to note that these five styles are each named after a specific clan, which does not seem to have happened in the previous styles of the region.

Although in all probability the Southern Shàolín Temple never existed, the legend circulated in martial artist circles of the time and is deeply rooted in folklore.

We have already mentioned (The Burning of the Southern Shàolín Temple) how this story is first recorded in the founding mythology of the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiāndìhuì 天地會), a secret society that began as a mutual aid association and would later become involved in uprisings and anti-government activities. Later martial arts novels would contribute decisively to the propagation of this myth.

The Shàolín Monastery in Hénán 河南.

The rise of the five family styles coincides with the time of the first rebellions of the secret societies and with the emergence of the mythology of Southern Shàolín. It was the influence of these styles that spread the legend of the burning of the temple to other styles such as Wing Chun 詠春 and Choy Li Fut.

It is possible that Southern Shàolín, if it has any historical basis, was not a physical place but an association, that is, a group of people linked by some kind of affiliation to the Northern temple, although in this case it is unlikely that all those associated with the organization were in fact so. In any case, many martial artists of the time claimed to have learned from monks from the southern temple, including two of Chan Heung's teachers.

We will discuss the alleged revolutionary activities that stem from this myth in a later article. For now, we recommend reading our articles on the Southern Shaolin Temple and the Secret Societies to have a better understanding of essential aspects that we are going to deal with in this history of Choy Li Fut.

Chan Heung's first teachers

Chan Heung was born on August 23, 1806 in the village of King Mui 京梅 in the district of San Woi 新會 in Gong Mun (Jiāngmén) 江門, Guǎngdōng Province.

At the age of seven he went to live with a distant uncle of his, Chan Yuen-Wu 陳遠護, under whose tutelage he began his instruction in Chinese martial arts. Chan Yuen-Wu is said to have been a disciple of a Southern Shàolín monk named Duk Jeong.

Chan Heung demonstrated exceptional skill in Kung Fu, and by the age of fourteen he had mastered all the knowledge his uncle could pass on to him, being able to beat any competitor from neighbouring villages in combat. His uncle wanted the young man to continue learning, so he decided to take him to an old friend of his, Li Yau-San 李友山.

Li Yau-San was the founder of one of the branches of the Li Ga Kyun 李家拳 style, one of the five "family styles" of Southern China and, again, he is said to have learned from a Southern Shàolín monk named Zi Sin 至善.

Zi Sin is a legendary figure found in the founding stories of many Southern styles associated with Southern Shàolín, including the five family styles and even Wing Chun. In these stories, Zi Sin is the abbot of the temple, and one of the monks who escapes its destruction to pass on the martial arts. Some versions claim that Li Yau-San himself was a monk.

Li Yau-San had an herbal medicine shop in the San Woi district, and there Chan Yuen-Wu went with his apprentice to ask his former friend to accept him as a disciple. That's how Chan Heung met his second teacher.

Another version of the encounter between Chan Heung and Li Yau-San

There is another version of the story according to which Chan Heung and Li Yau-San had already met before:

Li Yau-San's fame as a fighter was well known throughout the region. Once, when he was resting at a tea house in the area, Chan Heung, having heard of him, decided to test his skills attacking him by surprise. When Li Yau-San was leaving the tea house, he grabbed him from behind to try to knock him down, but Li used the seipingma 四平馬 or horse stance to secure himself to the ground, and his opponent could not move him. After the initial surprise, Li Yau-San counterattacked, exchanging several blows with Chan Heung, and again he was surprised by his ability.

Li Yau-San rebuked Chan Heung for his attitude, and the young man asked for forgiveness assuring that he had simply wanted to test his skill, but never cause harm to him. However, the master of Southern Shàolín was impressed by the qualities of the young man.

Under Li Yau-San's supervision, Chan Heung spent the next four years devoting himself thoroughly to the training of the Li-style Kung Fu. In such a short period of time, Chan Heung had once again reached the level that had taken his masters a lifetime to reach, and he was ready to continue on his way.

Li Yau-San, after considering the matter in depth, wrote a letter of recommendation and decided to send his disciple to Mount Luó Fú 罗浮山 in search of the person who will become his third teacher: the legendary monk Choy Fook 蔡褔.

Martial Arts instruction in Guǎngdōng in Chan Heung's time

At this point, we can ask ourselves several questions. What was martial arts instruction like at this historical moment? Who sought this instruction, and how did they pay for it? Finally, for what purpose was this knowledge sought to be acquired, and how did the martial artists of the time live?

In the time of Chan Heung's youth there were no martial arts schools as we understand them now. Schools with professional teachers required students to have money or surplus rice to pay their fees and, at the same time, free time to devote to the study of the discipline.

These commercial schools would emerge at the end of the nineteenth century in urban centres as a result of a monetized economy, first in Fújiàn 福建 and then in Guǎngdōng, and Chan Heung's students would benefit from this change. But, at the time we find ourselves, they did not yet exist.

On the other hand, when we talk about the great masters of the past, we imagine prestigious people valued and respected by the local community. But this was not the case in Chan Heung's time. Certainly, a teacher was greatly respected by his disciples, but martial artists were not generally well regarded by general society, and they did not necessarily enjoy either prestige or approval.

So, who was looking for instruction?

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, except for those seeking a career in the army, martial arts apprentices in the civilian field were generally peasants, who needed martial skills to defend themselves against bandits.

Banditry was a major social problem in rural areas. The economic prosperity of the first half of the dynasty and the consequent growth in population led to a decrease in the size of cultivated land per capita. When all the available land was being cultivated, the only way to increase production was to intensify human labor and the irrigation and fertilization of the fields.

As population grew, the size of farms decreased, and farmers had to work more, but earned less. In addition to an exodus to the cities in search of work, this phenomenon led to an increase in banditry, and crops were preyed upon by outlaws from neighboring villages.

Thus, peasants sought training in martial arts, but the time they dedicated to training was governed by the agricultural calendar. Their main task was still to work the fields, and they studied martial arts usually after the harvests, when the produce was sold.

At this time, fairs and markets were held that attracted wandering martial artists who offered instruction to the local population.

How instruction was paid for

The economy of rural areas was poorly monetized. Most people did not have access to cash, and many payments were made in kind. When a family wanted their children to learn martial arts, they could invite a recognized teacher to live in their home, providing him with lodging, food, and clothing. Generally, the best teachers were supported by a single family, which in this way ensured the instruction of their children.

Another way was to send a son to a master's household as a servant. In this way, the young man would work and assist the master's family in domestic service, and in return would receive instruction in martial arts. This was the case with Yáng Lùchán 楊露禪, founder of a style of Tàijíquán 太極拳 and, possibly, also that of Chan Heung.

Although this was not always the case, when a student went to live with the teacher it was because he was looking for a military career. At that time, anyone looking to make a career in the army needed to pass military exams, and these people were looking for martial instruction in order to do so.

Sometimes, a group of students could mantain a teacher in common, paying together for shared instruction, although it was difficult for this purpose to come to fruition in large groups. Chan Heung himself would teach in the future according to this formula.

Although Chan Heung's family was of peasant origin, it seems to have been reasonably well-off, as the young man apparently received a privileged education for his time and social context.

In rural areas, such as King Mui, illiteracy was widespread. There were rural schools that provided the children of peasants with a very basic culture. We know that Chan Heung knew how to read and write, as he left some writings and composed some duìlián 對聯 for the altar of the schools.

Who practiced martial arts?

As we have said, martial artists had probably received their instruction to defend themselves against bandits. Those who excelled in their skills could aspire to make a living from them, although it was not a prestigious activity and, surely, they were driven to it by poverty or the impossibility of farming profitable land.

Apart from a few reputed teachers who could be hired by wealthy families to teach their children, most seem to have made a living in other, less prestigious ways.

One of them was as traveling acrobats and opera performers. They depicted battle scenes and required some knowledge of martial arts. We have already seen (The Differentiation of Styles in Kungfu) how it was in this recreational field that the first proper styles emerged, while in the army an effective technical corps was trained, but not systematized in the form of coherent styles.

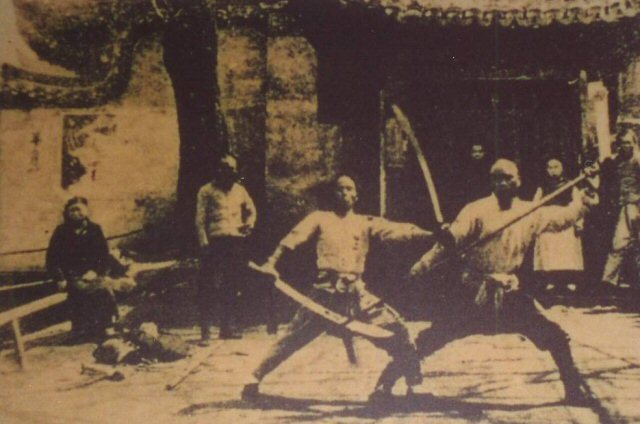

Wandering martial artists.

Another occupation was that of doctors and sellers of herbs and potions. They used martial arts as a lure and made demonstrations of their strength and ability to receive blows, an ability supposedly provided by their medicinal formulas. Many were street vendors who traveled between different villages, usually at the time of harvest festivals, when peasants had money to spend and time to acquire martial instruction. It is possible that Chan Heung's own master, Li Yau-San, had operated in this area.

A third occupation was as a private escort or as a member of a company of armed guards (biāojú 鏢局). These escorts protected merchants who transported valuable goods en route between different locations. To learn more about these companies, see The Armed Escorts of Martial Artists in the Qīng Dynasty.

None of these occupations carried any prestige, dignity or social acceptance.

If you were lucky, you could end up instructing rural militias. In the last years of the eighteenth century, the use of local militias (tuánliàn 團練 or yǒngyíng 勇營) was introduced to deal with regional uprisings that the regular army corps could not deal with efficiently. The formation of these militia corps also prevented the local population from joining rebellions.

These militias were made up of a peasant population on a compulsory, although paid, service. Its financing was in charge of the local gentry. Mercenaries were also often hired. These troops of "braves" (yǒng 勇), as they were called, were equipped with sabres and spears and, perhaps, old-fashioned firearms, but lacked modern weaponry.

In the 1840s, when Chan Heung would be active as a martial arts instructor, there existed near the city of Guǎngzhōu 廣州 a corps of 10,000 hired mercenaries that could be mobilized if necessary, in addition to a reserve force in the villages of several tens of thousands. These forces were involved in the first Opium War against British forces. Most of these practitioners studied a technical repertoire useful in combat, but not necessarily codified in a specific style.

Finally, those who could not earn an honest living resorted to banditry and used their martial skills to rob and assault villages or caravans. Secret societies, which were initially mutual aid associations, but later became forces that fought violently for control of local resources, used martial arts as a lure to recruit followers. These societies used martial arts instruction as a means of transmitting their ideology and superstitions.

Of all these occupations, it is possible that Chan Heung sought to enter the army through the imperial examinations –although we do not have news of him ever trying to do so– or perhaps to become an instructor for local militias –which there are indications that he did.

In any case, he was spending a lot of time, effort, and possibly money on his martial training when he said goodbye to Li Yau-San and went in search of his third master.

In Search of Monk Choy Fook

The narrative of Chan Heung's meeting and stay with his third teacher is full of legendary elements and, surely, has more of a legend than of historical fact.

According to oral tradition, Choy Fook was a former monk from Northern Shàolín who had abandoned monastic life to live as a hermit on Mount Luó Fú. He was known as the "burned-head monk" (làntóu héshàng 爛頭和尙), due to the ugly scars he had after getting burns with incense while taking the Buddhist vows.

Chan Heung made his way to Luó Fú Shān, asking everyone he met on his way about the whereabouts of Choy Fook. Arriving at a small temple high on the mountain, he found an older man wearing a cap, whom he asked again about the monk. The man told Chan Heung that Choy Fook was not there at the time and didn't know when he was going to return. Chan Heung decided to wait there until the monk returned, and such was his insistence on staying there without leaving, that finally the man recognized that he was the person he was looking for. When he took off his hat, the scars on his head were revealed.

Chan Heung then handed him Li Yau-San's letter and asked the hermit to accept him as a disciple, but to his disappointment he refused. Chan Heung insisted on his plea, but Choy Fook had no desire to teach martial arts and only accepted Chan Heung as a student to transmit the Buddhist teachings to him.

Chan Heung decided to stay. He spent his time studying Buddhism with Choy Fook and practicing meditation during the day, and training his Kung Fu alone at night. It was only after a long period of time when the monk was testing his apprentice that he became fully convinced that he was worthy of receiving the teachings and secrets of the arts of Shàolín.

Putting Chan Heung to the test

Legend has it that early one morning, Chan Heung was training by kicking stones up and hitting them before they fell again. Seeing this, Choy Fook walked over and asked if that was all he was capable of. Pointing to a millstone weighing about thirty pounds, he asked him to throw it twelve feet away with a kick. Chan Heung managed to meet the challenge very narrowly, and was surprised when the monk kicked the stone up with no apparent effort.

Chan Heung again begged Choy Fook to teach him, and this time his request was finally accepted, with three conditions. First, Chan Heung had to stay with Choy Fook long enough to learn everything he had to teach him; second, he promised not to use his skills to kill or injure anyone, and to behave with humility; and third, he had to kick the millstone back to its original place.

After accepting the monk's conditions and kicking the stone back into place, Chan Heung was finally accepted as a disciple.

Chan Heung spent eight years—more by some accounts—learning Kungfu from monk Choy Fook and getting instruction in the practice of Buddhism. In addition, he learned the secrets of herbal medicine and how to reposition bones and joints.

Some believe that Choy Fook resided in an ancient Taoist temple in the Mount Luó Fú area, called Temple of the White Crane (Báihè Guān 白鶴觀), although this is impossible to confirm. Today, the temple is within a military zone with restricted access and is impossible for civilians to visit.

Old photograph of the Temple of the White Crane (Báihè Guān 白鶴觀), on Mount Luó Fú 罗浮山.

A new path

When Chan Heung was twenty-nine years old, his teacher decided that he was ready to embark on a new course, and he entrusted him to return home to dedicate himself to the transmission of Shàolín Kung Fu.

龍虎風雲會

lung fu fung wan wui

徒兒好自爲

tou ji hou zi wai

重光少林術

zung gwong Siulam seot

世代毋相遺

sai doi mou soeng wai

(Cantonese phonetic transcription)

The dragon and the tiger met like the wind and the cloud

My disciple, you must take good care of the future

To revive the arts of Shàolín

Don't let future generations forget this teaching

Words of the monk Choy Fook as he said goodbye to Chan Heung

Choy Fook is said to have encouraged Chan Heung to transmit martial arts in order to overthrow the corrupt Qīng 清 dynasty and restore the Míng dynasty (fǎn Qīng fù Míng 反清復明). As we will see later, this is probably just a legend, with a later origin.

In 1836, after saying goodbye to his master and returning to King Mui, Chan Heung systematized all his martial knowledge in a new style of Kung Fu, which he named Choy Li Fut.

The meaning of Choy Li Fut

According to the most widespread opinion, Chan Heung chose the name Choy Li Fut to refer to his teachers Choy Fook and Li Yau-San with the first and second characters, respectively. Equally widespread is the belief, often confused with the former, that Li refers to Li Ga Kyun and Choy to Choy Ga Kyun, thus referring to styles, rather than masters.

With the third word, Fut, which means Buddha in Cantonese, Chan Heung would have wanted to honour the Shàolín Buddhist roots of his new system.

It is also widely believed that Choy Li Fut combines elements of Southern styles with those of the North.

In our view, these issues are not without questions. First of all, it is unclear what style of Kung Fu Chan Yuen-Wu taught Chan Heung. There has been speculation about whether it could be Fut Ga Kyun 佛家拳, which would explain Choy Li Fut's third character consistently, although this opinion is disputed.

Other oppinions favour Hung Kyun 洪拳. This is not at all far-fetched, since both systems, Hung Kyun and Choy Li Fut, share a good number of principles and characteristics.

There are those who relate him to some northern style, because of his way of handling the spear. Finally, it is also possible that Yuen-Wu had practiced several styles and did not teach his nephew any particular style.

On the other hand, it is usually assumed that the style that Choy Fook taught Chan Heung was Choy Ga Kyun, one of the family styles of southern China, and yet tradition tells us that Choy Fook came from the north.

It is reasonable to think that Yuen-Wu taught Chan Heung a Southern style and Choy Fook, if he was originally from the Shàolín Temple in Hénán 河南, a Northern style. If so, Choy Li Fut's Choy would be a reference to Chan Heung's last master, and not to the style of Choy Ga Kyun.

Chan Heung initially returned to his home village of King Mui, where he established an herbal medicine clinic called Wing Sing Tong 永勝堂. Soon after, the village elders invited him to open a school in the clan's ancestral hall to teach the new system, which he named Hung Sing Gun 洪聖館, after a local deity named Hung Sing 洪聖 (Great Sage).

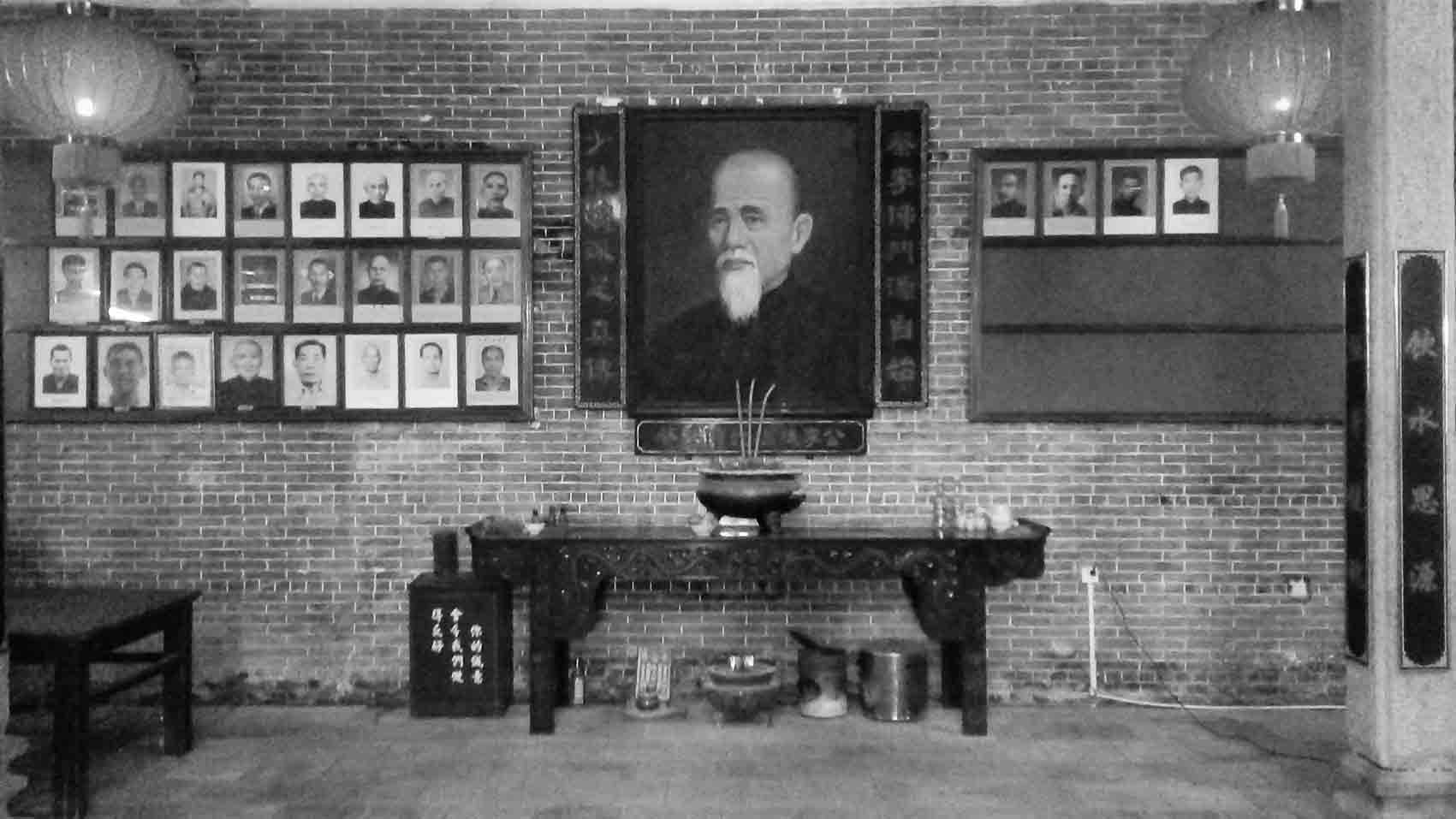

King Mui 京梅 ancestral hall, today.

In the years that followed, accounts of Chan Heung's activity became confusing and contradictory. He is said to have accepted invitations to teach in different locations in Guǎngdōng, Guǎngxī 廣西, Hong Kong 香港, and even in Southeast Asia.

Apparently, he was hired in the village of the Chan clan in the district of Shùndé 順德 (today part of the neighboring city of Fóshān 佛山) as an instructor for the militias. The basis of militia training was the staff and butterfly knives (húdiédāo 蝴蝶刀), weapons that are part of the essential repertoire of the Choy Li Fut style.

It is important to note that, when we talk about the militias instructed by Chan Heung, we are referring to militias formed by the local gentry that, although they were not part of the regular Qīng army, fought as government support troops; not rebel militias.

Be that as it may, the truth is that his fame spread quickly and he received students from different places.

Some say that, at the dawn of the Opium War, he was called by Lín Zéxú 林則徐, the imperial commissioner sent to Canton to curb the drug trade, and whose actions triggered the first war, to train troops in Guǎngzhōu. But oral tradition tells us that he himself fought in the Opium Wars; it is understood that as a "brave" (yǒng) or mercenary, since there is nothing that leads us to suppose that he joined the army. If so, either Chan Heung did not keep his promise to Choy Fook—not to use his abilities to do harm—or such a promise never existed.

Imperial commissioner Lín Zéxú 林則徐.

It is possible that troops trained by Chan Heung participated in the fighting that, in 1854, stopped Chén Kāi 陳開's forces from attempting to join the siege of Guǎngzhōu by Lǐ Wénmào 李文茂. This possibility is interesting because it would place Choy Li Fut fighters fighting against troops led by members of Tiāndìhuì, the Heaven and Earth Society, with which Choy Li Fut and Chan Heung would be associated in later mythology.

Later, during the Tàipíng rebellion 太平天國, it seems that Chan Heung refused to fight, although it is possible that among his students there were some who supported the rebellion. It is possible that his identity as a convinced Buddhist aligned him against the rebels, whose leader believed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ and was trying to cleanse the country of the heresies of Buddhism and Taoism. It is also very likely that Chan Heung simply harbored no hostility to the Manchu government.

Despite everything, there are sources that try to relate him to the revolution. According to them, after being involved, either directly or through troop training, Chan Heung would have escaped to Hong Kong to avoid subsequent repression. There is no evidence to support these claims. Moreover, by this time many of Chan Heung's students had dispersed to nearby regions to transmit their master's teachings, founding schools that operated openly without apparently arousing suspicion from the Qīng government or suffering any repression.

It is indeed possible that Chan taught in Hong Kong at some point, when he was invited there by some relevant person.

Some people think that, on his travels to teach the style, Chan Heung was invited to San Francisco, in the USA. Apart from there being no evidence of such a trip, the claim is quite far-fetched.

Choy Li Fut's sounds

Chan Heung is said to have established a series of battle cries in Choy Li Fut: wat 挖 when executing the tiger claw, tek 踢 when kicking, jik 抑 when striking with palms and fists, etc. In this way, even when they were in the middle of a battle, Choy Li Fut practitioners could recognize each other, collaborate and protect each other.

Theoretically, Choy Li Fut is considered to have five set sounds or battle cries. However, only the three mentioned are usually common to all lineages.

This theory of sounds as a way of recognizing each other reminds us of the symbolism of secret societies, which established signs and gestures with their hands, as well as secret slogans by which to recognize their members.

According to oral tradition, on his return from his travels, Chan Heung again made the way to Mount Luó Fú to visit Choy Fook, but his teacher had already died at the age of 112.

Chan Heung died in 1875, at the age of 69, and was buried in his home village of King Mui.

Another image of Chan Heung 陳享.

Conclusions

From 1848 onwards, Chan Heung's students, who had initially all belonged to the Chan clan, dispersed throughout the nearby regions and provinces and established schools to continue transmitting Choy Li Fut Kungfu outside the clan.

Many of these schools are already modern, that is, public and commercial institutions of martial arts education open to anyone who paid their fee. Their main clientele were urban workers who came to these centres for reasons other than the acquisition of martial instruction (we will return to this topic when we discuss the Hung Sing Gun 鴻勝館 of Fóshān).

In addition to his many disciples, Chan Heung passed on his knowledge to his two sons, Gun-Bak 陳官伯 and On-Bak 陳安伯. It was these practitioners and teachers who established Choy Li Fut as one of the main and most powerful styles in South China in its own right. Chan Heung's style is also the main heir to Li Ga Kyun, of which there are not many practitioners left today.

By the end of the 19th century, Choy Li Fut had become the most popular combat system in the entire province of Guǎngdōng, numbering several thousand practitioners, and overshadowing other contemporary styles such as Wing Chun or Hung Kyun. However, as we will also see, its popularity declined significantly after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Sources:

Hamm, John Christopher. Paper Swordsmen: Jin Yong And The Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel, 2005 University of Hawai’i Press.

Dian H. Murray, Qin Baoqi. The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History, 1994 Stanford University Press.

Benjamin N. Judkins, Jon Nielson. The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. University of New York Press, 2015

Laurent Chircop-Reyes. Illegal Caravan Trade and Outlaw Armed Escorts in the Qing Dynasty: Critical Analysis of Two 18th Century Memorials, 2023.

Laurent Chircop-Reyes. Merchants, Brigands and Escorts: an Anthropological Approach of the Biaoju Phenomenon in Northern China. Ming-Qing Studies, 2018.