The triads, criminal organizations, had their origins in a split of the Hung Mun Society, or Society of Heaven and Earth, a secret organization that fought for the overthrow of the Qīng dynasty in the later years of the Chinese imperial era.

The character huì 會, in traditional Chinese: "society" or "association".

Introduction

The Hung Mun 洪門 Society (in Cantonese: Hóng Mén in Mandarin), also known as the Society of Heaven and Earth (天地會 Tiāndìhuì), was a secret organization whose activity focused during the 19th and early 20th centuries on the overthrow of the Manchu-origin Qīng 清 dynasty that ruled China.

This society declared themselves loyal to the deposed Míng 明 dynasty, and was engaged in revolutionary activities, with which many martial arts practitioners in Southern China sympathized.

A branch of this secret society would give rise to triads, organized crime groups inside and outside China. However, this was not the original purpose of Hung Mun society, nor was, at first, the fight against the Qīng dynasty.

Historical background and socioeconomic context

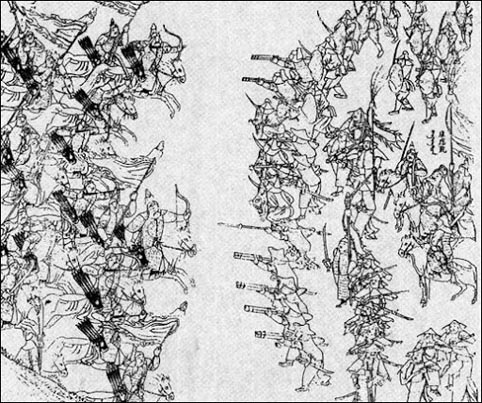

After the taking of Běijīng 北京 by the Manchus in 1644, some groups of opponents escaped southwards and openly continued the armed struggle for a while. The bond between the individuals who made up these groups was the sworn brotherhood, in the way that, in the famous episode of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義 Sānguó Yǎnyì), Liú Bèi 劉備, Guān Yǔ 關羽 and Zhāng Fēi 張飛 would be sworn in in the peach garden.

This would be the model of society (huì 會) through which the so-called secret societies would be formed.

Confrontation between Manchu and Míng 明 troops.

During the 18th century, southern China experienced demographic pressure that pushed certain social groups into marginality. These groups were made up of ethnic minorities and immigrants from other regions of China, such as the Hakka 客家 (this is the usual romanization of the Cantonese term; pronounced kèjiā in Mandarin).

The Hakka (literally, "guests") had been migrants from the provinces of Hénán 河南 and Húběi 湖北, further north, but had settled in the southern regions several generations ago, so members of the Hakka community were not themselves immigrants, although they retained their own language, different from Cantonese and Fukienese, also called Hakka.

Over time, the term Hakka also encompassed other migrant ethnic groups, even if they did not speak the Hakka language and, in general, any outsider.

On the other hand, the local native Cantonese speakers were known as Punti 本地 (literally "native" in Cantonese; běndì in Mandarin). Punti came to see Hakka population growth as a threat, relegating them to marginality and pushing them to live in the hills, away from fertile land for cultivation. Marriage relations between the two ethnic groups were very rare.

Resentment between the two groups was growing until it led to violent conflict.

Thus, the Hakka and other marginal groups began to cluster into secret societies outside the law, which were born with the aim of dealing with the socio-economic well-being of their members. These individuals also sought to build new collective identities outside the prejudices imposed on them by general society. Unlike Punti settlers, who belonged to ingrained local family lineages, the communal organizations that the Hakka formed were based on language and birthplace.

Only about fifteen such societies appear in historical records before 1755, and nowhere is the restoration of the Míng dynasty mentioned as its objective. It was not until after 1755 that some 200 new groups would emerge. One of them was the Tiāndìhuì.

Secret societies

The term "secret society" is a Western denomination. Although they operated underground, and their members tried to go unnoticed, societies such as Tiāndìhuì were more or less known at the local level. Although, if the government discovered any of its members, they were imprisoned, exiled or executed, secret societies proliferated in some way because they met needs not met by other legal associations, providing social, economic and religious support.

These groups developed their traditions and their own forms of organization outside of other legal social entities, and provided marginal individuals with a sense of collective identity that allowed them to collaborate with each other, without needing to know each other, to achieve common goals. Under no circumstances were these political organizations.

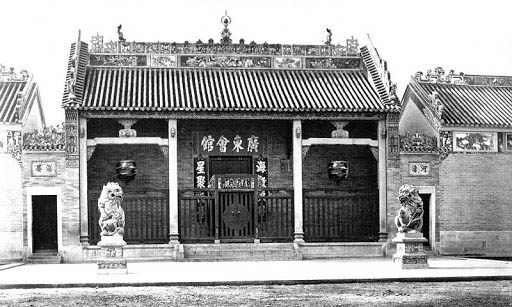

These societies acted similarly to the huìguǎn 會館 (guildhalls), providing financial support, accommodation and regulating trade, with the difference in which huìguǎn were established by official organizations and focused on upper classes, while secret societies were made up of marginal members of society, such as the Hakka. In this way membership of these societies was a way to ensure survival for their members.

Facade of an official huìguǎn 會館 in Guǎngdōng 廣東 province .

The foundation of the Tiāndìhuì Society

The Tiāndìhuì Society was founded in 1761 by a monk named Tíxǐ 提喜, whose real name was Zhèng Kāi 郑开, along with other individuals in Zhāngpŭ 漳浦, Fújiàn 福建, near the border with Guǎngdōng 廣東. Its original purpose was, as we have already said, mutual assistance among its members.

The group began to attract the attention of the Qīng government after two uprisings in 1768 and 1787 in Zhāngpŭ and Taiwan 台灣, caused by disputes between different families, and which ended with hundreds of detainees by the government.

The reason for these conflicts seems to have been above all the use of land and water, and there is no evidence that there was an anti-Manchu feeling.

Continued repression of secret societies led to conflicts between them and the state. After the 1787 uprising in Taiwan, the imperial government began to label these socio-religious associations as seditious.

The initiation ceremonies and rituals performed by the Tiāndìhuì were aimed at creating a sense of unity, of brotherhood as part of a large family (like the name Hung Mun itself, "Great Family", suggests), which transcended blood lineages and territorial ties, and not to encourage rebellion against the state.

Initiation rites

The Tiāndìhuì Societies were also religious groups that took their beliefs from Buddhism and Taoism, and their rites from local cults with which the population was already familiar.

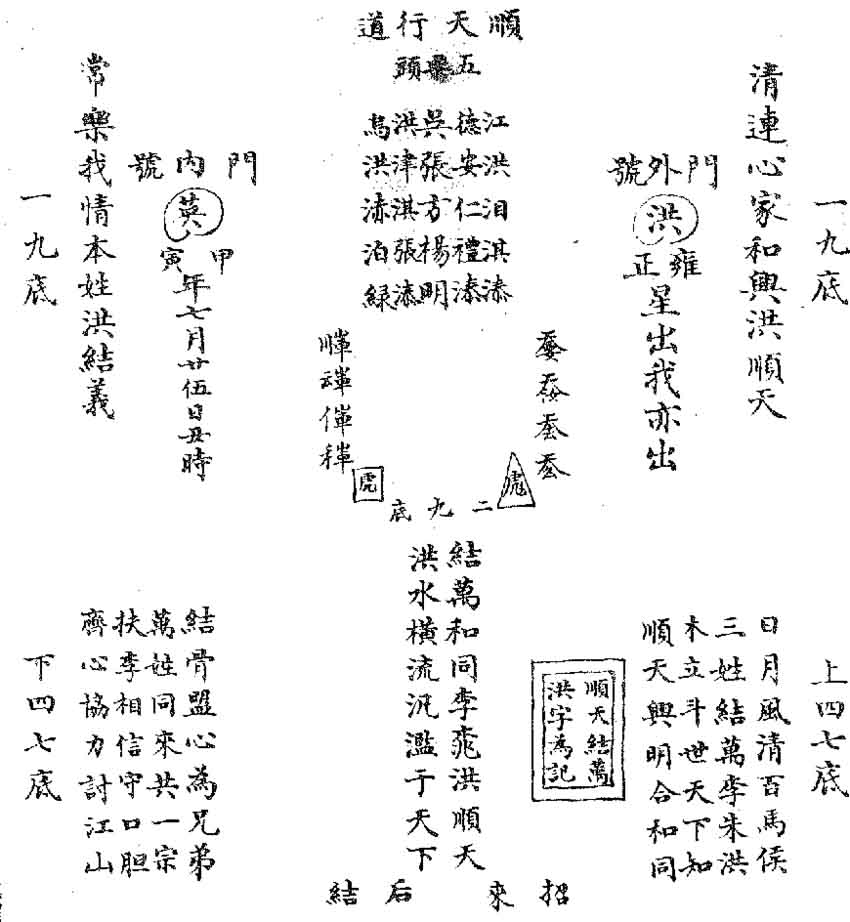

Under the motto "Follow the Way in the Name of Heaven" (替天行道tì tiān xíng dào), or "Follow the Way in Obedience to Heaven"(順天行道shùn tiān xíng dào), the initiation ceremonies of the new members were a rite of passage: the transition between a figurative death and the rebirth to a new life as a member of society.

It is said that the initiates sacrificed a rooster before an altar with incense and took the oath of brotherhood. Late reports say they mixed the blood of a rooster or chicken with wine or ash, and sometimes with the blood of the initiate himself, taken from a cut on one of his fingers, and drank it.

The members of Tiāndìhuì recognized each other by marks in the apparel, by certain agreed gestures or by the password "five dots, twenty-one" (五點二十一 wǔ diǎn èrshíyī), which would refer to the word Hung 洪, in addition to its motto already mentioned. When they entered the organization, some members changed their last name to Hung.

In the left column, two forms of the character Hung 洪, or Hóng in Mandarin,

which consists of five dots, diǎn 點 (right-top in red), a horizontal line and two verticals that can also be written as two crosses, which individually correspond to the character "ten", shí 十 (right-centre in red), and a horizontal line of the character "one", yī 一(right-down in red).

This way of reading the word Hung 洪 would result in the password "five dots, twenty-one" (五點二十一 wǔ diǎn èrshíyī).

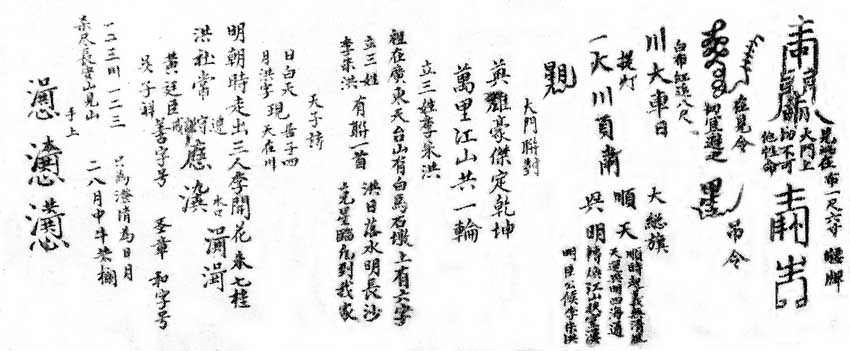

The society handed over to its members certain certificates or oath books (盟書 méngshū), which served as a membership registration and as identification, as well as acting as talismans protecting against disease and evil spirits. The characters Heaven (天 tiān), Earth (地 dì) and Hung (洪, hóng in Mandarin) were also used in these talismans, written in cryptic styles typical of Taoist magic.

Writing on a piece of paper used as a talisman.

Split

In the face of the spread of the Tiāndìhuì through different provinces, it was branched into different groups, such as the so-called Sānhéhuì 三合會, "Society of the Triple Union", and Sāndiǎnhuì 三點會, "Society of the Three Points".

These groups went on to be responsible for armed uprisings, some of a few individuals, others up to two thousand, motivated by expectations of personal gain.

Based on the names of these groups mentioned above, the British called secret societies "triads", a term used to refer to them without distinction between criminal groups and mutual aid societies.

The Tiāndìhuì uprising of 1802

In 1802, in the mountains of Hùizhōu 惠州, Hakka communities formed secret societies that spread throughout the Hakka-majority area, in the border region between Guǎngdōng, Fújiàn and Jiāngxī 江西.

The escalation of tension between Hakkas and Puntis, for reasons already explained, led both groups to the formation of paramilitary units, whose sole purpose was self-enrichment through looting, attacking Punti markets and villages and, in the case of the latter, defense against these attacks and revenge.

Tiāndìhuì groups recruiting members to attack neighbouring villages were surprised before acting, and 23 of their components were summarily executed by the government.

Other members escaped to adjoining regions, where they regrouped and joined other Tiāndìhuì groups. By the summer of 1802 there were already several thousand members. Led by a man named Chén who they called Lànjīsì 陳爛屐四 (literally, "Broken Shoes the 4th"), they moved with their families to the mountains where the stored food and weapons.

Banner used by Chén Lànjīsì 陳爛屐四.

For a month, these huìfěi 會匪 ("society bandits", as they were called) went down from the mountains to plunder Punti villages until, in October 1802, Chén was captured. His followers retreated and continued to cause trouble.

Meanwhile, the Punti, who had organized themselves into a society called "Ox Head" (牛頭會 Niútóuhuì), captured another Tiāndìhuì leader named Wēn Dēngyuán 温登元, who was handed over to the authorities, and he died while in custody. In the face of this, several Tiāndìhuì leaders grouped with their units and continued attacking Punti villages in retaliation.

Several thousand imperial soldiers were sent to quell the conflicts. In turn, the Punti organized militias and recruited mercenaries to protect themselves. The situation of the Tiāndìhuì became desperate, until they managed to break through and escape.

In the Boluó 博罗县 region and what is now Zǐjīn 紫金縣 in Guǎngdōng, these episodes left more than 200 villages affected, possibly tens of thousands dead, ruined crops and disrupted living conditions. The emperor decreed a tax exemption for three years to allow economic recovery.

The Qīng government confiscated lands of the leaders of Tiāndìhuì; many of them never returned to their homes but were reinstalled elsewhere.

Revolutionary activities

Historians disagree on when the rhetoric of Míng restoration appeared in secret societies. The Tiāndìhuì texts are obscure and difficult to interpret.

It seems that by 1800 there were already allusions to the Míng restoration in some oaths of initiation in the societies of Guǎngdōng. Also, the Tiāndìhuì society has been linked to certain mesianic cults, which predicted the end of the world and the coming of a savior.

Foreign invasions are, for Chinese mesianic cults, one of the indications of the end of the world. These cults also understand the figure of the savior as an ideal and just ruler or king. Some frequent words used in slogans relate this savior to the surname Zhū 朱, the same one beared by the Míng imperial family, and some have seen in the word Hung, the name of the first Míng emperor, Hóngwǔ 洪武.

A Tiāndìhuì 天地會 coin, possibly used as identification among its members, and/or as a protective talisman. Among the words inscribed on it, one is the name of the first Míng emperor, Hóngwǔ 洪武.

It was also intended to see reference to the Míng dynasty in the combined use of the separate characters rì 日 and yuè 月, which together form the word míng 明.

In addition, a Tiāndìhuì banner has been found in Hùizhōu with a cryptic slogan, 木立斗世天下知順天興明合和同 mù lì dǒu shì tiān xià zhī shùn tiān xīng míng hé hé tóng, intranslatable because of its cryptic meaning, which some scholars have interpreted as predicting the fall of the Qīng dynasty and the Míng restoration.

In short, references to the Míng dynasty, although obscure, are not scarce. However, despite these findings, the recorded confessions of the members of Tiāndìhuì show that most of them did not understand their cryptic meaning. Another fact to keep in mind is that the targets of Tiāndìhuì were not the Manchu military garrisons, but Punti villages. Possibly the conflict between Tiāndìhuì and the Qīng government originated first as an expansion of the Hakka-Punti conflict.

On the other hand, it seems that the Qīng dynasty itself worked to interpret the Tiāndìhuì rhetoric as anti-Manchu. Similarly, it is possible that the Tiāndìhuì society found in the Míng restoration a justification for its activities, a form of legitimacy in the eyes of the rest of the population.

It is believed that for this purpose of legitimation the founding myth of the society was invented, which refers to the burning of Shàolín 少林 and the survival of the Five Elders (少林五祖 Shàolín wǔ zǔ), which we have already talked about in our article The Burning of the Southern Shaolin Temple. These five surviving monks would form, in coalition with descendants of the Imperial Míng family, the Tiāndìhuì Society.

Be that as it may, the truth is that the 19th century saw a steady increase in the involvement of the Tiāndìhuì society in revolutionary activities, such as the Tài Píng rebellion (太平天國 Tàipíng Tiānguó), one of the bloodiest in Chinese history, or the Rebellion of the Red Turbans. By this time, the society had ceased to be a system aimed exclusively to support migrants, and had assimilated to local communities, engaging in violent activities. Anti-Manchu sentiment had become widespread, and the Tài Píng rebels committed massacres annihilating the entire Manchu population in some cities.

After the Opium Wars, more and more poor peasants joined the Tiāndìhuì to ensure their survival, and again new branches of this society appeared.

Tiāndìhuì and Martial Arts

Choy Li Fut 蔡李佛 early masters reportedly trained poor peasants to be part of armed militias and nurture revolutionary groups. The motto Hung Sing 洪勝, "victory for the Hung family," was common among early practitioners of the style. The word Hung 洪 was later changed to hung 鴻 "goose" and hung 雄 "hero", homophones in Cantonese, to encode their original meaning and avoid risks.

After the fall of the Qīng dynasty, these societies that had made the overthrow of the dynasty their main activity, lost their raison d'être and switched to organized crime. Members of these triads traveled to neighboring countries in Southeast Asia to continue their illegal activities, where they still operate today, as well as in southern China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and other Chinese communities abroad such as the US.

Sources:

Qin Baoqi, Dian H. Murray, The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History

Robert J. Antony, Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, Chinese Secret Societies and Popular Religions Revisited: An Introduction

Robert J. Antony, Ethnic and Religious Violence in South China: The Hakka-Tiāndìhuì Uprising of 1802

2 thoughts on “Secret Societies and the Origin of Triads”

hello Brothers , i always wanted to train in serious Chinese Martial Arts and other combat systems , Since my childhood this was my secret dream and ambition , to learn as much as i can and to Train as much as i can and carry on learning and training ,now i am 42 years old

in my city we have a Chinese community they had a club too but extreme politics and stupid jealous feuds pained my heart , i tried to train and learn and be a part of it but i was always wronged and misunderstood , the hypocrites took extreme pleasure in sabotaging my training , brothers i might be old but i still have it in me , but in the name of god you have to trust me , i don’t want to be a superhero just an ordinary man but with knowledge and training .

We are sorry to hear about your experience, Anirban. We hope you can find a better place to keep training Kungfu.

Wish you all the best!